12 Vintage Nicknames For Alcohol That You Don't Hear Anymore

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Before alcohol was a branded, bar-coded commodity, it was a wild and often illicit part of everyday life. There have been dozens of nicknames for alcohol throughout its long tenure, with each providing a thoughtful reflection of the time period. Some eras put huge taxes in place while others banned alcohol altogether, but it never stopped consumers. If they were one thing, it was determined. Aside from the abundance of speakeasies and surge of creativity alive during prohibition, the alcohol ban ultimately hurt the U.S.

Many of these vintage terms reflected the quality (or lack thereof) of available alcohol, with names like "rotgut" and "coffin varnish" painting vivid pictures of what drinkers could expect. Others, like "giggle water" and "mother's ruin," captured the social attitudes and effects associated with different types of liquor. While contemporary craft cocktail culture has given us new terminology, these historical nicknames offer a fascinating glimpse into how our ancestors talked about drinking, and what traditions we've hung onto. Most of these terms have faded from the modern vocabulary, surviving only in period literature and the occasional nostalgic revival, yet their legacy lives on.

Hooch

Amongst this jumble of words, hooch, short for hoochenoo, is probably the most well known term for alcohol. If used today, it's typically in a coy or witty manner, like a play on words or a nod to the retro term. With context clues, it's easy to figure out what "hooch" means, but few know the true origins. It's an Alaskan term for a stiff spirit that was popular for bartering in the late 1800s, derived from the region's Hoochinoo tribe. It was originally made from molasses, flour, and, of course, sugar, but overtime it just became associated with any cheap DIY liquor.

The term gained widespread popularity during Prohibition, when bootleggers produced countless varieties of illicit alcohol in bathtubs, basements, and hidden stills. Much of this homemade liquor was dangerous, containing toxic additives or inadequate distillation products, but desperate drinkers were typically quick to settle. Back in 1927, 98% of the bootleg liquor NYPD seized was reported poisonous. While the word occasionally surfaces in present-day contexts, it started dropping from everyone's vocabulary by the '60s.

Mother's ruin

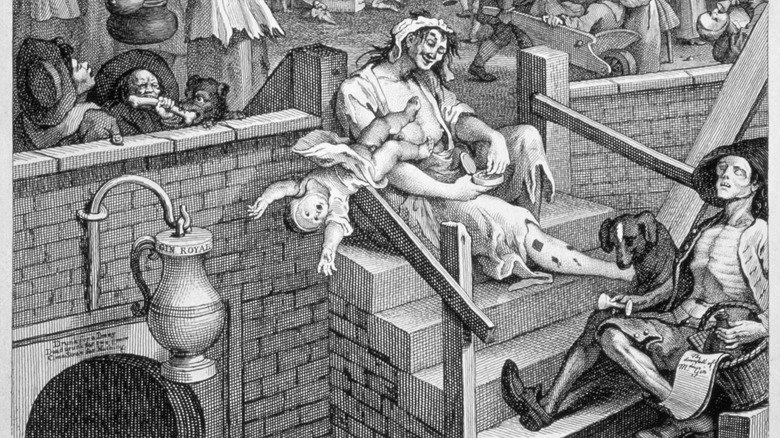

The origins of the term "mother's ruin" date much farther back than the U.S. prohibition. In the late 1700s, bootleg gin was the cause of London's chaotic streets, at least, that's what propaganda pushed. Artist William Hogarth encouraged the idea that bootleg gin was the curse behind London's downfall with "Gin Lane," his now famous 1751 etching. Women were especially targeted, as their primary role in society was bearing children, and alcoholism halted that trajectory. "The destitute, drunken mother or wet nurse became the poster person for a new temperance movement," Mallory O'Meara shares in her book "Girly Drinks: A World History of Women and Alcohol."

British authorities eventually implemented heavy taxes and regulations that curtailed the gin fever, but the nickname stuck around well into the 20th century. It often appeared in literature and social commentary as a reminder of gin's presumed destructive potential. The term began fading after World War II, once gin took on the complete opposite persona of an elegant, sophisticated liquor.

Rotgut

If you break down the word it's easy to see the origins of the nickname: rot-gut. The name alone tells you what to expect, but other than the fiery burn, there wasn't much consistency to the spirit. "Rotgut" emerged in the American frontier era as a brutally honest description of low-quality whiskey that seemed to burn and corrode everything it touched. The term's imagery was deliberately graphic, suggesting that the liquor was so harsh it could literally rot a person's stomach. This wasn't entirely hyperbole, as much frontier whiskey was poorly distilled, contained impurities, and sometimes included dangerous additives to enhance potency or mask poor quality.

Like many of these terms, it evolved into a catch all for low-grade liquor, but primarily whiskey. During the 20th century, bourbon started plummeting in popularity. It was seen as "an old man's drink at best, good ol' boy Southern rotgut at worst," as author Aaron Goldfarb puts it in his latest book "Dusty Booze: In Search of Vintage Spirits."

White lightning

This Nascar-sounding nickname for moonshine was made popular in the Great Smoky Mountains and then carried on beyond the mountain peaks. Each sip jolts through your body like a shock of electricity, true to its name. Because of the clandestine process of making moonshine, it can come in varying potencies, flavors, and even different colors (sometimes). Especially high strength, clear moonshine, received the title of white lightening. "White lightning was colorless and biting, and it usually had to be drunk with a flavorful mixer to mask the foul taste," W.J. Rorabaugh explain in his book "Prohibition: A Very Short Introduction."

It all started in the rural mid-America, and the South, particularly in Appalachian regions, where illegal distilling became both a necessity and a tradition. The nickname captured the clear, translucent appearance of unaged corn whiskey and its sudden, powerful effect on drinkers. Unlike aged whiskeys that gained amber color from barrel storage, moonshine was typically consumed fresh from the still, maintaining its crystal-clear look. These days, you're likely to see commercially-produced liquors on Appalachian store shelves boldly boasting the once clandestine name of moonshine. However, it's far less likely that you'll find a bottle called White lightening.

Giggle Water

Popular in the Roaring Twenties, "giggle water" was a flapper-era euphemism for booze, typically champagne or any bubbly cocktail. Light, fizzy, and liable to produce laughter, it captured the carefree, jazz-soaked spirit of the era. During Prohibition, slang like this served a dual purpose: it was cute and coy, but also discreet, allowing people to talk about drinking without drawing legal attention.

The boozy nickname appears in 19th century novels, speakeasy menus all over the country, and even early films. It evokes sequins, cigarette holders, and the clink of coupe glasses. Unlike some harsher nicknames, this one framed alcohol as glamorous and fun — a liquid form of rebellion and joy. The term was so adored that Charles S. Warnock even named his bartender's cookbook after it. "Giggle Water" was published in 1928 and the cover was the epitome of 1920s glamour, champagne flutes and flapper dresses on full display. The cute phrase is rarely heard today, other than Gatsby-themed parties or retro commercials.

Coffin Varnish

"Coffin varnish" painted a grimly humorous picture of alcohol so toxic it could preserve the dead, and the term emerged during the late 1800s when quality control in liquor production was virtually nonexistent. Frontier saloons often served whatever they could obtain cheaply, regardless of safety or palatability, hence the term "coffin varnish." Some establishments actually did serve alcohol containing wood varnish, industrial alcohol, or other dangerous chemicals that could blind, paralyze, or kill unsuspecting drinkers.

The nickname served as both warning and dark comedy among patrons who understood the risks but had few alternatives, or just shrugged it off. Cowboys, miners, and travelers developed gallows humor about their drinking options, and the so-called coffin varnish captured the fatalistic attitude toward potentially deadly beverages. Bartenders sometimes used the term themselves, either as honest disclosure or morbid advertising that suggested their liquor was strong enough to kill. Prohibition ironically made the nickname more relevant than ever, as bootleggers frequently used industrial solvents, antifreeze, and other poisonous substances to create their products.

Horse liniment

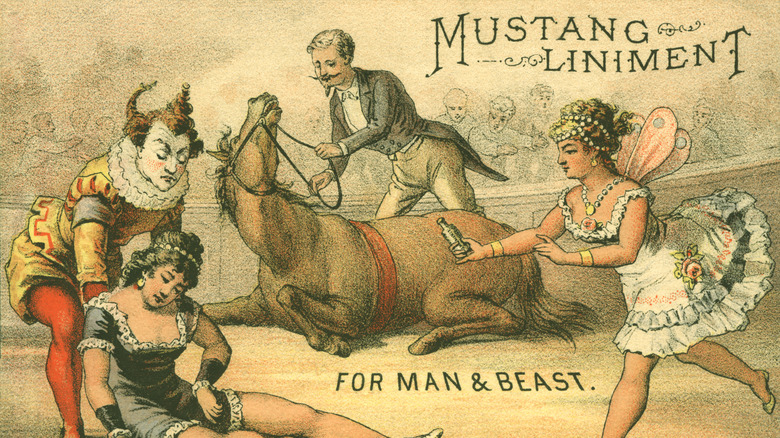

Another Prohibition nickname with dark humor, "horse liniment" refers to alcohol that was so harsh and medicinal that it seemed more appropriate for soothing a sore horse than drinking. During America's ban on alcohol, people weren't against turning to medicinal tinctures or pharmaceuticals just to catch a buzz, even from the veterinarian. In addition to getting you drunk, alcohol has cooling properties that help settle a horse's discomfort when added to salves.

Horse liniment, typically a camphor or menthol-based topical treatment, had a strong smell and taste, not unlike the denatured spirits of the era. So, when people drank extremely low-grade or repurposed industrial alcohol, the nickname made cynical sense. The U.S. government had no problem spiking ethanol with toxic chemicals, knowing full well it was dangerous for human consumption but wouldn't stop drinkers. Like "rotgut" or "coffin varnish," it proves the extremes people would go to for a drink when the whole country was dry. Once the legal sale of liquor resumed in the U.S., the term dwindled from the general public and remained in the vet's office.

Tarantula juice

"Would you like a glass of tarantula juice?" might sound like a horror movie punchline, but in the 1920s, it was slang for extremely potent bootleg alcohol, particularly stuff that made you feel like six legs were crawling all over your skin. The phrase likely gained traction among speakeasy-goers and flappers who wanted to keep it light and satirize the current state of affairs, but it originated in the eastern Sierra Nevada, where the creepy crawlers were abundant.

This nickname typically applied to the absolute worst whiskey available. We're talking, "last bottle on Earth" level of desperation. The comparison to tarantula venom wasn't entirely figurative, as some frontier alcohol actually contained toxins that could cause hallucinations, paralysis, or death. Unscrupulous dealers might add anything from strychnine to tobacco oil to enhance potency or disguise poor quality, creating beverages that genuinely rivaled spider venom in toxicity. Strychnine only existed on the market as a cure for pulmonary disorders, but it could also cause a euphoric high when diluted into the harsh alcohol, and that was the not so secret ingredient of Sierra Nevada's tarantula juice.

Panther Sweat

Panther sweat, while not exactly appetizing, was one of many colorful nicknames for homemade whiskey during Prohibition, particularly in rural communities. It hints at the fierce, unregulated nature of black-market booze, riddled with deadly compounds like embalming chemicals or creosote. Panther sweat was a popular term throughout the 1920s, but never fully broke into mainstream slang outside of Kansas. The goofy term doesn't have much subtext, in the same vein as "monkey-swill and rat-track whiskey," like the 1929 edition of Duke University's "American Speech" points out. Basically any liquid following "panther" became a term for shoddy alcohol, like panther breath and panther juice, but panther sweat was one of the most common.

A so-called Old Panther whiskey was universally adored in Old Western themed cartoons like Looney Tunes and Tex Avery as a running joke. The imaginary bottom of the barrel whiskey brand was a salute to panther sweat and the poisonous liquor folks happily consumed. Like many Prohibition-era terms, panther sweat began fading as boozin' rules loosened up. Post-war American drinking culture leaned towards classier, more straightforward terminology, and these '20s phrases seemed outdated at suburban cocktail parties.

Mountain Dew

Long before it became a caffeinated soft drink, Mountain Dew was a poetic nickname for moonshine whiskey produced in the hills and hollers of Appalachia. The term captured both the geographic origin and the pure, clear quality of well-made mountain moonshine, suggesting something natural and refreshing rather than industrial and harsh. Unlike many alcohol nicknames that emphasized danger or poor quality, Mountain Dew carried positive connotations of craftsmanship. Appalachian distillers took great pride in their product quality, using local spring water, corn, and traditional techniques passed down through generations. "Mountain Dew" suggested fresh ingredients and connection to the land, distinguishing craft moonshine from the mass-produced junk or dangerous bootleg operations.

The nickname's transformation began in the 1940s when beverage inventors Barney and Ally Hartman chose Mountain Dew for their new citrus soda, initially marketing it as a mixer for whiskey. PepsiCo eventually acquired the brand and transformed it into a mainstream soda pop, completely divorcing it from alcohol associations. Modern consumers only recognize Mountain Dew as a soda brand, but older bottles illustrate the anticipated buzz alongside the words, "It'll tickle yore innards!"

Tanglefoot

Tanglefoot was another name for backwoods moonshine or harsh whiskey — alcohol so strong it could make your legs wobble and your tongue sound swollen. The term likely comes from the visual of someone so drunk they can't walk straight, stumbling as if caught in invisible bear traps. It was also, notably, a brand of flypaper at the time, which added a layer of sticky irony: this booze might not trap flies, but it would definitely trap you in a long, hazy night.

Tanglefoot was especially popular in the American South and Midwest throughout the Old Western days, often used in jest among those who knew they were drinking something far from refined. Like many of its slang siblings, it dwindled as alcohol became legal and production more standardized. But every so often, you'll still find "tanglefoot" resurrected by craft distillers or bars with a sense of humor.

Devil's candy

"Devil's candy" transformed alcohol into something simultaneously tempting and dangerous, playing into the taboos of drinking. The nickname mocked religious imagery that portrayed drinking as moral temptation disguised as pleasure. It emerged from Protestant communities where religious leaders regularly condemned alcohol consumption as sinful and destructive.

The comparison to candy was particularly clever, as it captured alcohol's ability to provide immediate gratification while creating long-term problems. Just as candy could rot teeth and ruin health despite its sweet taste, the devil's candy implied that alcohol offered temporary pleasure at the cost of spiritual and physical wellbeing. During Prohibition, the term took on new meaning as illegal alcohol literally became forbidden fruit that many found irresistible despite legal and moral prohibitions. The era's tensions between desire and duty, pleasure and propriety were palpable, and this nickname perfectly captured that. However, as American attitudes toward alcohol became more secular and moderate after Prohibition's repeal, religious metaphors like "Devil's candy" caught some serious push-back.