10 Fish You Shouldn't Use For Sushi (And Why)

Sushi is one of those foods that looks like it can be executed simply at first glance, but done well it's an art form that hinges on precision, technique, and close attention to detail, and it all begins with choosing the correct fish. Freshness is only the first step. Some fish carry a higher possibility of parasites. Others simply don't work well in terms of texture or taste when consumed raw. Sustainability is another concern, and sometimes, you may not even be eating what the fish is claimed to be!

As sushi becomes more popular, restaurants have started to take a shortcut or jump on the bandwagon by adding fish to their menu that probably shouldn't be there. Be it mislabeled snapper, fish that can upset your stomach, or an endangered species, these alternatives can compromise both the safety and traditional integrity of a dish.

To gain a better understanding of what fish to avoid and why, we spoke with some sushi chefs. Okaru's Chef Marc Spitzer, Saijo's Kazuya Takebe, and Uchi West Hollywood's Joel Hammond gave industry insight into the kind of fish that, ideally, shouldn't be used for sushi. From health to ethical issues, their input helped shape the list below. If you care about what's on your sushi plate (and you really should), this guide will give you an idea of what fish to avoid when ordering or building your roll.

Escolar

Escolar is among the more controversial fish you'll ever see on a plate of sushi — and in some eateries, you might not even know it's there. It's typically listed under the misleading title of "white tuna." Escolar resembles a rich, buttery substitute for more expensive fish like albacore, but it can leave you with digestive sickness.

Okaru chef Marc is adamant about the issues with escolar in sushi, and for good reason. "That fish contains super high levels of wax esters in it," he says. Those are natural chemicals that are essentially indigestible fats, and consuming them, even in moderate amounts, can result in unpleasant side effects like gastrointestinal distress. For others, that can translate to anything from cramps to the urgent need to find the nearest bathroom. Despite the risk, escolar continues to be used at restaurants because of its silky texture and lower price. Some chefs may not know what they are buying at all since seafood mislabeling remains widespread. "A lot of fish is mislabeled," says chef Marc. "Even the restaurants don't always know.".

Escolar's dangers are not related to spoilage or poor handling — it's an inherently poor option in the first place, even when fresh. That makes it different from other fish that can be made safe by proper preparation. It's one thing to have an unfamiliar fish on a plate for creativity's sake. It's another to have something that causes people to be sick. If you see "white tuna" on a menu or at the grocery store, ask questions. If it's escolar, don't use it.

Net caught fish

Though taste or freshness might top the list for most folks prepping or ordering sushi, the method by which the fish is caught is just as (if not more) significant. For Chef Hammond, there is one practice that's completely off the menu: "Do not serve net-caught fish!" he says firmly. "Net fishing is terrible for the environment and fish populations."

Net fishing, especially large-scale methods like trawling or gillnetting, is well-known for devastating marine environments. The heavy equipment often results in excessive bycatch, which get entangled, discarded, injured, or killed during the process. That includes not just other fish, but also sea turtles, dolphins, and other ocean animals. In most cases, entire seafloor ecosystems are churned up or destroyed..

From a quality standpoint, net-caught fish also lose. When fish are trapped for longer periods of time, they can become very stressed, affecting both taste and texture. Bruising, spoilage, and inconsistency are the outcomes. Line-caught fish, by contrast, are less stressed and handled more carefully; therefore, they arrive fresher.

Fresh water fish

Freshwater fish are also one of the worst choices when it comes to sushi quality and safety. As Chef Hammond bluntly puts it: "Freshwater fish in general tend to be the worst options for sushi. They can have higher levels of parasites and generally aren't suited for sushi." The majority of ocean fish do not have that issue, as freshwater fish tend to be infested with parasites, which in raw form can prove to be harmful.

Even if parasite problems are taken care of, many freshwater fish are still lacking in texture and taste. Rainbow trout, for instance, is sometimes used in sushi by chefs trying to innovate — but it rarely works. "Rainbow trout is far too soft and needs to be cured, cooked, or smoked," explains Hammond. If served raw, its delicate flesh turns mushy and disgusting, far from the clean, snappy bite that sushi is renowned for.

Beyond the attributes of individual fish, there's also the bigger culinary expectation. Classic sushi is all about harmony and deference to ingredients. Freshwater fish don't pass the test here, owing to their absence of structure or subtlety. The softer textures and comparatively bland flavors are easily overpowered even by simple seasoning, which destroys the whole bite. While experimentation is part of what maintains modern sushi, some boundaries exist for a reason. When it comes to freshwater fish, the risk to flavor, texture, and health is too high to make them sushi-appropriate.

Mislabeled red snapper

Red snapper is a familiar name at sushi restaurants, where it appears on menus labeled tai, and is prized for its mild flavor and clean, slightly sweet finish. What many consumers are not aware of, though, is that "red snapper" is one of the most mislabeled fish in the seafood industry— and mislabeling can become a critical issue when being consumed raw.

Red snapper is frequently substituted for less costly, similarly named fish in North America, specifically, like rockfish, or other so-called "snappers" that aren't authentic American red snapper. These substitutes will look like the real thing after being filleted and displayed in seafood sections, but are most likely not the same in quality or taste. Some of these imitators aren't particularly well-suited for raw consumption. They are more likely to harbor parasites or simply lack the clean, firm bite that is so pleasing with high-quality sushi. And since many of these fish are seldom eaten raw in their native cuisines, there's less information available on how to prepare them safely for sushi service.

The issue is less about the fish and more about the lack of transparency. When restaurants get the fish wrong, even by accident, they undermine that trust. As chef Marc described it, "things like American red snappers are constantly being subbed with a different type of snapper that might look the same but is a completely different fish." If you see red snapper listed on a menu or filleted at a grocery store, don't hesitate to ask follow-up questions. If the establishment can't respond with confidence, it might not be the fish you imagine it to be, and it likely won't be sushi-appropriate.

Bluefin tuna

Bluefin tuna is a prized fish in the sushi world for its deep color, melt-in-your-mouth texture, and decadent taste. But where its worth as a luxury lies is its issue: the tuna has been heavily overfished for decades, raising issues of sustainability and morality that have haunted sushi culture for decades. Okaru's chef Marc just says: "I think this conversation will always go towards bluefin tuna, which has been overfished for many years. Its stocks are on the rise, but nowhere close to where it once was. It's the most prized fish for sushi restaurants, so it's a constant conversation to serve or not to serve it, but will always have its place as king of the fish in sushi restaurants."

This ongoing controversy between honoring tradition and honoring environmental boundaries places wild bluefin as among the more controversial options on any sushi menu. While there are currently chefs and wholesalers who opt to substitute farmed bluefin for more sustainable alternatives, its conservation status ebbs and flows. As chef Marc continues, "While buying farmed bluefin tuna is promoting the population to become larger in the wild, there is still an extreme concern regarding overfishing of the wild group as a whole."

The question of whether to order and purchase bluefin is not an ethical conundrum about conservation, but one about responsibility. With bluefin on the menu alongside other types of tuna, diners and cooks must ask themselves if bluefin for dinner is worth the health of the ocean. In a time when transparency and sustainability matter more than ever to consumers, wild-caught bluefin illustrates how even high-quality, esteemed ingredients deserve a pause.

Poorly handled mackerel

Mackerel has long been a staple in traditional sushi because of its bold flavor and fatty texture. But unlike some other sushi staples, mackerel is very delicate to handle, and if not handled correctly, it can pose some serious health risks. Chef Marc puts the danger succinctly: "I think some of the mackerels, when not treated properly, can have parasites." That danger is the same reason that mackerel requires special attention before it even reaches the sushi bar. Typically, the fish must be cured in vinegar or lightly salted to reduce the possibility of parasites. Bypassing that step risks safety as much as flavor.

A less skilled home cook, or a cost-cutting restaurant, may not always follow traditional preparation methods. This is especially the case with sushi being more globalized and commercialized. Mackerel has a shorter 'shelf life' than fish like tuna or yellowtail, meaning it can spoil quickly in flavor and texture if not handled with precision. Even minor mistakes in temperature control or cutting can result in an off taste, a mushy consistency, or even unsafe fillets.

That's why veteran sushi chefs continue to treat mackerel with extra caution. When it's done right, it's a star example of balance, with its bright acidity from curing, stacked atop a clean, briny richness. Mackerel isn't a fish to avoid altogether (we don't want you to be too conservative in experimenting with your sushi choices!), but it's one to be wary of in the wrong hands. If you're not at a reputable sushi spot or if the fish seems off, it's wise to pass. When it comes to mackerel, careful preparation isn't optional — it's essential!

Never-frozen salmon

Unsurprisingly, Salmon is the most popular North American sushi choice. What few salmon enthusiasts are aware of is that raw, never-frozen salmon is a health risk when eaten raw.

Chef Marc said, "Some items like salmon should be frozen for a bit to help kill these parasites as directed by the FDA." Unlike naturally saltwater-living species from birth, most salmon travel between freshwater and saltwater, becoming more susceptible to parasites like tapeworms. That's why freezing salmon in commercial sushi restaurants is not just preventive but obligatory. FDA rules call for fish to be frozen to specific temperatures for specific amounts of time before it's prepared raw to eliminate parasites. When salmon is properly frozen and thawed, it is completely safe and retains its flavor and texture. When, however, it's not frozen before serving raw, consumers are at real risk.

Despite these guidelines, some restaurants — especially those trying to sell "never frozen" fish as an indication of superior quality — will skip this step. It's a misunderstanding of what's required for fish to be considered sushi-grade. Serving raw salmon unfrozen is also indicative of a larger issue in the sushi industry: the gap between tradition and marketing. Freezing might sound like a bad idea, but when it comes to salmon, it's what gives protection without sacrificing quality. Next time you're enjoying a salmon roll or sashimi plate, consider asking how the fish was handled. If it hasn't been frozen first, even the best-looking slice might not be worth the risk.

Shark

While shark may appear on adventurous food menus or in specialty seafood dishes, it's a solid no from sushi aficionados. Chef Takebe is definitive: "Shark meat has a strong, unpleasant odor, which makes it unsuitable for raw consumption. It can be eaten when cooked."

That strong smell is usually likened to metallic or ammonia, and it's a result of how sharks manage waste in their systems. Unlike most fish, sharks release urea from their skin and tissues, which, upon death, degrades into ammonia. When not handled promptly, that smell only becomes stronger, rendering the meat extremely unpalatable, particularly when served raw. In addition to the smell, shark meat also has texture problems. It is mushy, rubbery, or fibrous when it is cut or kept for too long. These traits are at odds with what makes sushi superb: clean taste, balanced fat content, and a tender yet firm cut of fish.

While shark is sometimes eaten cooked in stews or broiled preparations, especially in certain coastal cuisines, its role in sushi doesn't exist in Japan. Its less-than-ideal attributes overshadow any novelty value, and its inconsistency makes it difficult to use raw. Even from a sustainability standpoint, most of the shark family is overfished and under threat. Simply put, shark meat just doesn't have a place on the sushi counter.

Swordfish

Swordfish is a staple in grilled seafood plates and grilled seafood steaks, but on sushi plates, it stands out like a sore thumb. Chef Takebe puts swordfish in his top list of fish he doesn't employ for sushi dishes: "Swordfish tends to have strong muscle fibers and a firm texture, which can be too tough and bland for sushi. It's better suited for cooked preparations like teriyaki.

"On initial inspection, the dense, meaty texture of swordfish may appear to be well-suited to sashimi. But its steak-like rigidity is precisely what makes it a no-no. Contrary to tuna or yellowtail (both of which provide soft, buttery textures) swordfish is not delicate. Its muscle fibers are coarse and chewy, providing more obstruction than elegance with each mouthful. The flavor doesn't serve it well, either. Swordfish has a mild flavor, sometimes even bland, and can taste flat when served uncooked. It does not possess the brininess of freshness or the richness of fattiness that quality sushi fish is capable of providing. According to Chef Takebe, swordfish is a far better option when cooked, softening its fibers and pairing well with teriyaki and other sauces.

In addition to texture and taste, swordfish presents certain health problems, especially concerning its mercury contamination, which is higher than all but a few commonly eaten fish, making it a hazardous choice for regular consumption, especially raw. Overall, swordfish is too firm, too flavorless, and too difficult to consume raw.

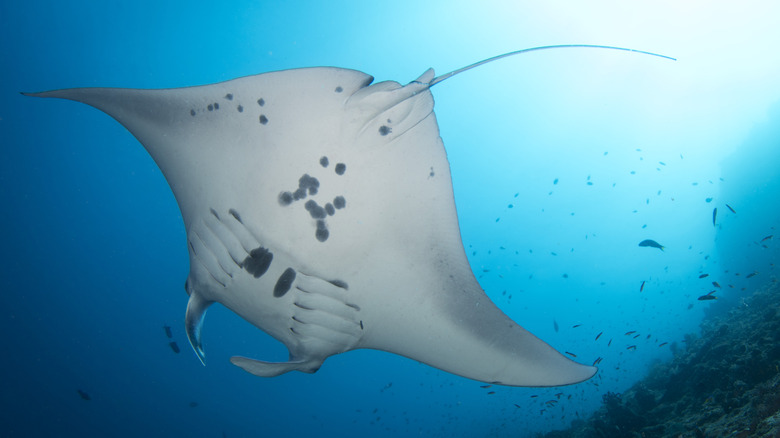

Ray

While ray is enjoyed in various cooked dishes around the world, there are superior options for sushi. Chef Takebe lists ray among the fish he rejects for raw dishes, explaining, "Ray meat has a strong smell and is overly soft, making it a poor fit for raw dishes. However, it can be delicious when deep-fried or simmered. In Japan, the fins are often dried and grilled."

The first issue with ray is its overpowering smell. Even when it's fresh, the meat carries a strong, at times ammonia-like odor, which is only more piercing when it's served raw. In a cuisine where freshness and clean taste are everything, that makes ray a hard sell. The smell alone threatens to overwhelm the rice, the seasoning, and the subtlety of the dish overall. And then there's the texture. Ray meat is usually too soft and gelatinous to stand up well raw. It doesn't have the firmness or structure to slice into clean sashimi or form into nigiri.

In cooked dishes, especially fried or stewed, these problems disappear. The flavor deepens, the texture firms, and its unique qualities are positives rather than negatives. But raw, ray just doesn't hit the mark. It has applications in the kitchen, but its applications don't include the sushi roll.