10 Modern Food Safety Rules No One Followed In The '70s

Many people tend to look back fondly at the 1970s as simpler times. This may be true, but the reality is that it was also a far more dangerous era. Even in developed nations, like the United States, public health regulations were severely lacking. Wearing seatbelts in cars was optional, and standardized guidelines to prevent driving while intoxicated were still developing. Lead-based paint was legal, asbestos use was widespread, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was still very much in its infancy. Food safety was equally — if not more — underappreciated.

It's impossible to understate the importance of enforced food safety rules. An estimated 600 million people fall ill each year as a result of unsafe food (per the World Health Organization). Of those, around 420,000 cases have fatal outcomes, particularly among infants. The U.S.'s first meaningful food safety legislation was passed in 1906 in response to the prevalence of adulterated food and drugs. It took a number of serious foodborne illness outbreaks in the late '80s and early '90s for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to finally publish its Food Code. Regularly updated, the Food Code contains what many of us now recognize as basic food safety guidance.

However, back in the '70s, many food producers and suppliers didn't have the knowledge we do now. Even those who did often ignored food safety when there were very few repercussions. Today, we're going to examine some of the modern rules that were rarely followed back then.

Compulsory hand-washing requirements for food workers

Foodborne illnesses are caused by harmful bacteria or viruses, which make us sick when they enter our system. Sometimes these pathogens grow in or on the food itself, but they can also be introduced through environmental factors. One of the most common ways dangerous microorganisms, like Salmonella and E. coli, are spread to food is through unsafe food handling practices. In a 2014 study, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined three years of data and found that 70% of U.S. norovirus outbreaks could be traced back to food workers. Over 50% of those outbreaks were a result of improper hand-washing procedures.

While that study proves that we still have a long way to go, hand hygiene guidelines were practically non-existent in the 1970s. There were no federal guidelines on handwashing for food workers, and hygiene standards were inconsistent among restaurants. It wasn't until 1993 that the FDA, with input from the CDC and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), published the first iteration of its Food Code. These were the first guidelines to recommend specific hand-washing procedures, including double-washing and the use of gloves when handling ready-to-eat foods. The Food Code also details when workers must wash their hands, such as after using the toilet or smoking, and recommends the use of dedicated handwashing sinks. So, while the risk of food workers contaminating food isn't zero, we can only imagine how low handwashing standards were in the '70s.

Meeting safe internal food temperatures

Even if food handlers strictly follow handwashing procedures, there are still ways for bacteria and viruses to enter our system. It's pretty much impossible to guarantee that raw foods won't harbor harmful microorganisms. We can try to prevent these nasties from reaching concerning levels with proper storage techniques, such as refrigeration, and by consuming food while it's still fresh. However, the last line of defense is heat. By cooking food, we can destroy the pathogens that would otherwise make us sick.

Today, we know the specific internal temperatures we need to hit to make food safe, but that wasn't always the case. In the 1970s, a cook's idea of "doneness" was pretty subjective, meaning there was a much higher risk of someone consuming undercooked food and becoming ill. Despite what some may claim, the idea that you can be sure food is fully cooked by sight is a dangerous myth. The USDA finally published safe temperature guidance in the 1980s, but even this advice only pertained to beef. This information was eventually added to the FDA's Food Code in 1993 and was updated in later revisions to include other types of meat, like poultry. Although meat thermometers have been around since the 1930s, they weren't really commonplace until food safety enforcement. Nowadays, meat thermometers can be considered an essential kitchen tool, and they're far more accurate and affordable than they were in the '70s.

Properly sanitizing food equipment and surfaces

We're not claiming that every 1970s restaurant was covered in filth and grime, but from a food safety perspective, there's a big difference between "clean" and "sanitary." Surfaces might have been wiped and cooking utensils washed, but just because something isn't dirty, that doesn't mean it's free of microorganisms. You'd often find staff reusing cleaning rags that should've been disposed of months before, or assuming cleaning with water and soap alone was sufficient.

In some cases, proper sanitization practices were lacking because restaurant owners didn't care, and there was no consistent safety enforcement. However, even those who valued food safety were likely uninformed when it came to things like sufficient chemical contact times or the difference between detergents and sanitizers. There was also little guidance surrounding the safe use of chemicals, so food workers were also at risk from using the cleaning products.

In 1989, Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) regulations began to address the dangers of improperly handled workplace chemicals by providing suitable guidance on topics like storage and appropriate use. Once again, proper guidance surrounding sanitation practices and cleaning schedules didn't become widespread until 1993 and the publication of the FDA's Food Code.

Not reselling or reusing uneaten food

If you haven't already been put off the idea of a 1970s dining experience, we think this entry might do the trick. There will always be businesses that prioritize profits over the safety of staff and customers if they're not afraid of being held accountable. It's pretty much the reason we have health and safety regulations in the first place. In the '70s, it wasn't uncommon for restaurants to reuse uneaten food to cut costs.

If a table didn't polish off their bread basket, there was a very good chance any leftover rolls would be re-served to someone else. Garnishes would be picked off plates and reused until they could no longer pass as fresh. Uneaten buffet items would be repurposed in subsequent dishes or reheated and sold again. Of course, these practices come with all sorts of health risks, whether it be cross-contamination of harmful pathogens between customers or eating food that's past its best.

While 1993's Food Code included guidelines that addressed reusing previously-served food, they were relatively vague. There are some instances where re-serving food is fine — bottled sauces on a table, for example — but these distinctions weren't added to the Food Code until 2014. The Food Code isn't federal law, and enforcement relies on state- or local-level adoption, so many states didn't regulate the re-serving of food until the additional guidance was published.

Avoiding cross-contamination of raw and ready-to-eat foods

Cross-contamination is the spreading of harmful bacteria from one thing to another. In terms of food safety, it can occur as a result of poor handwashing or cleaning procedures. One of the most common causes of cross-contamination is improper handling of raw products, followed by the handling of fresh or ready-to-eat foods.

Nowadays, avoiding cross-contamination is a cornerstone of food safety guidelines. As we mentioned earlier, the 1993 Food Code included regulations to address handwashing and glove use. However, it took another three years before the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) published its wordily-named report titled, "Pathogen Reduction; Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Systems; Final Rule." HACCP is intended to be a systematic approach to preventing foodborne illnesses by identifying and mitigating high-risk points in the food supply chain. This is why current health codes stipulate that raw products must be prepared on separate surfaces from fresh products.

Modern kitchens can use up to seven different types of color-coded cutting boards and kitchen knives for different foods to avoid cross-contamination. Back in the '70s, you'd be lucky if a restaurant had two separate boards for raw meat and "everything else." It was even more likely for a chef to use a single board for all foods. They may have cleaned it between uses, but that still wouldn't have been enough to eliminate the risk of cross-contamination.

Using unrefrigerated and unpasteurized eggs

One of the main culprits behind cases of food poisoning is Salmonella. This nasty bacteria can cause an infection known as Salmonellosis, a gastrointestinal illness that typically presents itself with abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and fever. It's an unpleasant experience at the best of times, and while it isn't inherently fatal, it can still be deadly. The most common sources of Salmonella are raw eggs and poultry.

There are many recipes that feature raw eggs as a key ingredient. While raw eggs can pose a higher risk than cooked eggs, they can be made safer through a process called pasteurization. Pasteurization has been around since the 19th century, so it wasn't exactly a new concept in the 1970s. However, even now, only about a third of eggs consumed in the U.S. are pasteurized.

Egg-related Salmonella outbreaks still occur today, so you can only imagine how much higher the dangers were in the '70s. Another risk factor was the lack of refrigeration in the supply chain. The U.S. washes its eggs to remove external bacteria. This also eliminates the protective outer layer — sometimes called the "cuticle or membrane" — making it easier for bacteria to permeate the shell. Refrigeration reduces the risk of further bacterial growth, but regulations mandating that eggs must be kept below 45 degrees Fahrenheit during distribution didn't come until the USDA's Final Rule in 1999.

Clearly labeling food allergens

Food allergies can vary in severity, but for many sufferers, a fast, fatal reaction is a very real and terrifying possibility. Exposure to an allergen can cause anaphylaxis in just a few seconds, so those with severe allergies have to be extremely careful to avoid exposure and often carry a lifesaving EpiPen with them. The number of people who suffer from food allergies has increased dramatically in recent decades. Studies indicate the number of children presenting food allergies soared 50% between 1997 and 2011, and another 50% between 2007 and 2021.

Unfortunately, while there are some theories as to why this is happening, none have been proven. Allergies are incurable, so the safest way to save lives is by following strict food preparation procedures and clearly labeling food ingredients. In the 1970s, there were no requirements for food producers to include allergen information on their products, so most of them didn't bother. The chance of having a food allergy may have been lower than it is today, but the risk of unknowingly consuming something deadly was far higher.

It took until 2004 for the FDA to implement the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA). This made it a legal requirement for packaging to state if a food item contained milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans. Sesame was only added to that list in 2023, and many allergy sufferers and medical professionals argue that further updates are required to save lives.

Smoking in food preparation and service areas

In the 1970s, roughly 40% of U.S. adults were cigarette smokers, compared to about 11% today (per the American Lung Association). Readers who were around in the '70s will remember just how prevalent smoking was, not just in terms of the number of smokers, but the fact that you could light up pretty much anywhere you wanted. You could smoke a cigarette in a cinema, the bank, or even on an airplane. Out of every occupation, smoking rates are almost always highest in the food service industry, so you can guarantee that some '70s chefs were smoking in their kitchens.

Nowadays, the health risks associated with tobacco use are well known, but that wasn't always the case. Even though connections were being made between cigarettes and lung cancer in the 1950s and '60s, policies aimed at reducing smoking rates were slow to appear. Not only were smokers putting themselves at risk, but their second-hand smoke also posed a danger to any non-smokers around them.

It wasn't until the '90s that some states began introducing laws banning indoor smoking. Even today, just 30 states, along with Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, have comprehensive indoor smoking bans for public spaces and workplaces. Fortunately, even in those states that don't have the same level of restrictions, smoking bans in restaurants are enforced near-universally at a local level.

Implementing use-by and sell-by dates

Nowadays, you'll notice that most pre-packaged food products come with some type of date label. In truth, "sell by," "use by," and "best before" labels aren't reliable indicators of whether food is safe or not. They don't tell us when food has expired; rather, they let us know when it's at its highest level of quality. They're also used by food retailers, so they know when to rotate or dispose of stock.

Although date labels aren't used as part of any food safety initiative, they're better than nothing. They give us a better idea of how long food is safe for consumption, and make it easier to trust that retailers aren't selling expired products. To date, there are still no federally mandated regulations regarding food-date labeling in the United States, with the sole exception being for infant formula. Fortunately, the practice started to become more commonplace in the 1970s without it being a legal requirement.

It still took until 2016 for the FDA's FSIS to release guidelines on date labeling to standardize date-labeling practices. In the '70s, however, many products lacked any kind of date label. You essentially had to trust that stores weren't pushing expired stock that should have been thrown out already. At least today, we can use date labels to make an informed decision before deciding whether our food is safe to eat.

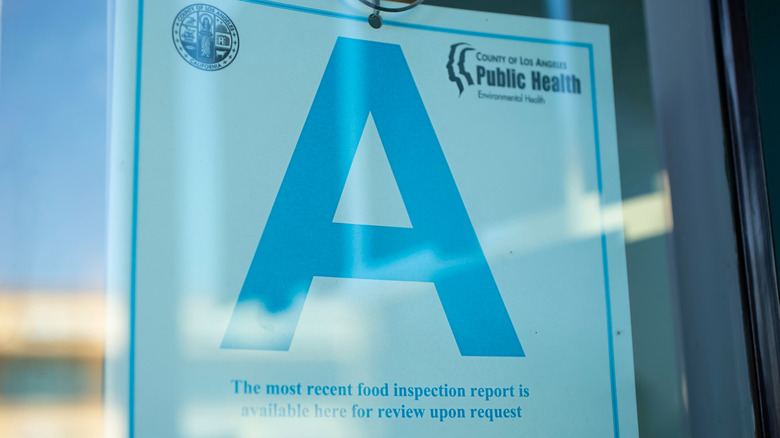

Conducting regular restaurant health and safety inspections

Food safety rules are ultimately useless if nobody ensures they're being followed. Nowadays, public health agencies inspect every part of the food supply chain, from farms to restaurants, to make sure local food safety regulations are being met. Most food businesses are assessed at least once or twice a year, often without advanced notice. If safety standards aren't being met, inspectors will issue a warning and attend a follow-up inspection to guarantee any problems have been addressed. They'll also investigate links to food poisoning outbreaks and can temporarily or permanently close businesses that violate the local health code. Most food safety departments have implemented a straightforward scoring system, and these scores are made readily available to the public.

As you've probably guessed, food safety inspections were practically non-existent in the 1970s. To be fair, there weren't many regulations to enforce at the time. Health departments lacked resources, so when inspections were carried out, they tended to be inconsistent if they occurred at all. Investigations were often reactive rather than preventative, taking place after people had already gotten sick, and there was little transparency. It was often impossible for members of the public to see the results of safety inspections. Once again, it took the publication of the Food Code in 1993 to persuade health departments to adopt standardized food safety assessment procedures. Today, all 50 states have adopted some variation of the Food Code and regularly enforce compliance.