The Seafood That You'll Probably Never See Again In The United States

For generations, wild abalone fed communities along the Pacific coast, from California to Alaska. Indigenous peoples from over twenty tribes, including the Chumash, Tongva, and Ohlone, gathered abalone in the tidal shallows, prizing not just the meat but also the shells, which they transformed into ornaments and tools. Abalone became a symbol of plenty and a vital part of seasonal feasts, traded up and down the coast for centuries. Evidence of this history can be found in ancient shell middens and the complex art made from shimmering fragments.

Today, the reality is stark. Wild abalone has become a seafood most Americans will never encounter, its place on the table replaced by memories and empty shells. By the 20th century, wild abalone captured the attention of chefs, divers, and seafood lovers. The meat is both sweet and firm, often compared to a cross between the sweetness of a scallop and the chewiness of calamari, with a subtle minerality that tastes like the deep, cold Pacific itself. Its popularity boomed in restaurants and private kitchens, but that demand also brought trouble. Years of overfishing, habitat loss, and poaching steadily reduced populations.

The rise of withering syndrome, a bacterial disease, added further stress, and as kelp forests dwindled due to climate shifts and sea urchin overpopulation, the decline accelerated. These days, wild abalone are endangered, and harvesting them in the U.S. is prohibited. Finding a shell washed up on a northern California beach feels almost like stumbling on a fossil, proof that abalone, once abundant, is now part of the coastline's memory.

When abalone was abundant

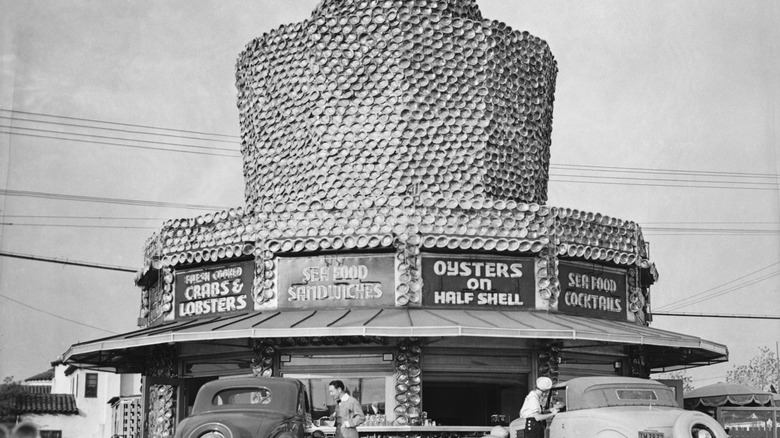

In the United States, wild abalone consumption reached its peak during the mid-20th century, when the California coast was dotted with old-school seafood shacks, supper clubs, and Italian and Chinese restaurants famous for their abalone steaks. Local divers and fishermen sold fresh catches to markets and diners, where abalone was pounded thin, breaded, and quickly pan-fried, served crisp at the edges and tender in the center. The dish was beloved for its delicacy and abundance, inspiring fishing derbies and even a culture of roadside "abalone burgers" for travelers. In these decades, abalone was a ubiquitous and celebrated part of everyday coastal life.

In China, Japan, and Korea, it remains a treasured food and a marker of celebration or status. Chinese cooks braise abalone in rich sauces for holidays, weddings, and high-end banquets. Dried abalone, intensely flavored and hard to source, can fetch astronomical prices. Japanese divers, many of them women known as ama divers, still free-dive for abalone as part of a tradition dating back hundreds of years, with the catch often eaten raw as sashimi or gently simmered. In South Africa and Australia, wild abalone is tightly regulated but still possible to find, though illegal poaching and export have taken a toll on stocks there as well.

Abalone's role as a luxury ingredient has led to controversy and change. Population exploitation (overharvesting), black market trade, and environmental shifts have placed stress on populations worldwide. Some regions have responded with strict quotas or complete closures, hoping to give wild abalone a chance at recovery. Even where it is available, wild abalone is increasingly rare, expensive, and politically fraught.

Clinging onto the shell of a warming world

For those who still want a taste of this underrated shellfish, farmed options offer a legal and accessible alternative. On small coastal farms, abalone are raised in tanks or ocean pens and fed kelp, separated from the wild's unpredictable currents. Many operations market their products as sustainable, and there are fewer risks of exploitation or poaching. Still, farmed abalone differs from its wild relatives. The flavor tends to be milder, the texture more uniform, and the experience generally less connected to the ecosystem that shaped the species over millennia. There are also questions about the broader impact of aquaculture, from water use to disease management, and debates about whether any farmed seafood can truly "replace" or make up for what's been lost.

Abalone are more than food; they are beautiful, strange creatures. They have a single, muscular foot for clinging to rocks and, like many sea creatures, are exquisitely sensitive to vibrations and water movement, a survival trait that helps them respond to predators and shifting tides. Still, their survival story is uncertain. Warming seas, acidification, and loss of kelp, their habitat and food source, challenge the hope of recovery, even if fishing remains banned.

As wild abalone disappears from local waters, the shells left behind tell part of the story, shimmering with rainbowed, mother-of-pearl bands refracting turquoise, pink, and green, a reminder that beauty persists even in absence. Choosing not to eat wild abalone is one way to support their recovery, but the future may depend as much on environmental action as on our eating habits. Abalone stands as a global symbol of what's at stake as we navigate changing oceans, part elegy, part ongoing experiment in care.