Does Molasses Actually Expire, And How Long Is Its Shelf Life?

If you bake regularly, there's a decent chance you own a jar of molasses with a sticky lid and an ambiguous air of old-timey mystery. It's not a pantry item that gets used very frequently, with one jar keeping for a while, so asking how long it lasts is a fair question. The short answer is reassuring, because molasses does not expire in the way other perishable foods do. Unopened, it can last over ten years. Once opened, it's considered shelf-stable, and most manufacturers give it a best-by window of about 18 months for peak quality, which allows for some wiggle room. In most real kitchens, properly stored molasses often lasts longer, gradually and subtly changing in flavor or texture before it becomes "unsafe".

Storage is the key factor here. Molasses should be kept tightly sealed in a cool, dark pantry, away from heat sources. Refrigeration isn't necessary, and can actually make molasses thicker and harder to work with, which is why many producers advise against it. Once opened, the biggest risk is contamination by way of moisture off of a wet spoon, steam drifting into an open jar, or not quite sealing the lid when you go to put it away. But while true spoilage of any one of the three different types of molasses is rare, it's not impossible.

Signs that it's time to toss a jar include visible mold on the surface, an actively fermented or sour smell, bubbling, or obvious signs of insect contamination. Changes like darkening, thickening, or mild crystallization are common with age and usually affect quality, not safety. In other words, molasses doesn't suddenly "go bad." It ages, and how gracefully it does so depends on how it's treated, so be intentional, and always be sure to use a clean spoon.

When good ingredients go bad

It can feel counterintuitive that something made from sugar doesn't spoil easily, since sugar is known as food for bacteria. The reason molasses keeps so well actually comes down to water, not sweetness. Microorganisms need water to grow. In foods with extremely high sugar concentrations, like molasses, that water is effectively tied up. Sugar is a humectant, meaning it binds moisture and creates an environment where most of the food-spoiling bad guys, like bacteria, yeasts, and molds, struggle to survive. This is the same basic principle that allows granulated sugar to sit indefinitely in a pantry without turning into a microbial party zone.

Molasses is densely saturated with dissolved sugars, which gives it strong natural resistance to spoilage. When problems do arise, they almost always start at the surface, where external moisture has been introduced. From a practical standpoint, this means most jars of molasses are a lot more durable than people expect. If it smells and looks clean and normal, and hasn't grown anything fuzzy, it's usually safe to use. The biggest change over time is flavor, which can either become flatter or more intense, if the volume has reduced, especially in very old jars.

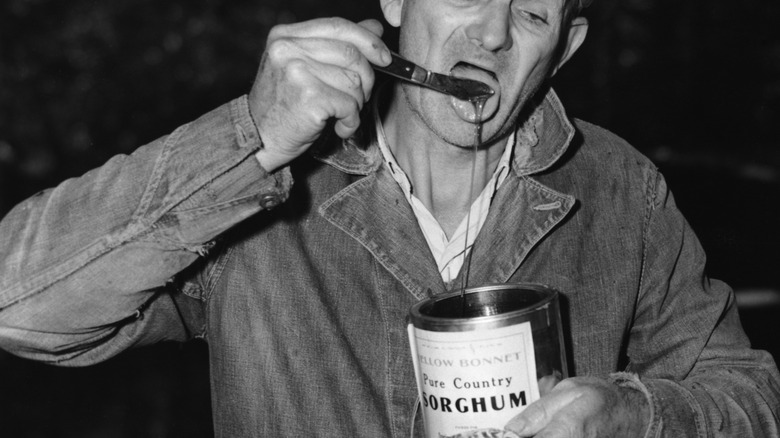

Molasses, like honey, was a common sweetener way before refrigeration, used in baking and brewing, and even animal feed, because it stored well and stayed usable across seasons. In some medicinal traditions, it was also valued for its mineral content, especially iron. Today, many of us only end up using molasses once or twice a year, often for old-fashioned gingerbread or baked beans recipes that call for just a few tablespoons at a time. Although there are some creative ways to make use of it, if you're going through your jar at a slow pace, that's probably fine.