19 Fascinating Facts About 18th-Century American Cuisine

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The 18th century was undoubtedly America's most significant period to date. Smack dab in the middle of the Era of Enlightenment, it was a time of exploration by land and sea, the emergence of great thinkers, and new beginnings for a brand new nation. By the 1800s, Britain's Industrial Revolution was spreading to America, making the 1700s the last era in which a rustic, close-to-nature way of life was the norm in our nation.

The 18th century usually conjures up images of ridiculous-looking wigs and battles for independence or land possession, while the food of the period is usually put on the back burner (pun intended). But North America is rife with diverse foods, from plants to wild game, that colonists were just beginning to experiment with on a large scale. Meanwhile, Indigenous people were making use of the abundant plant and animal resources that our verdant, bountiful land provides.

In this list, we'll take a glimpse into some 18th-century food facts that typically aren't made common knowledge in favor of wars and other milestone events that are more heavily associated with the time. But the foods eaten in the 1700s — by both colonists and the Indigenous population — shaped our modern cuisine, paving the way for iconic regional dishes and ingredients to become a hallmark of American culture.

1. There were foods specifically for sustaining travellers

Nowadays, when we're going on a long hike, we pack up some trail mix, candy, or protein bars. But in the 1700s, high-calorie, compact foods were far less easy to come by, so folks preparing for a long journey had to plan for provisions to sustain them on their travels. Portable soup — yes, soup that people carried in their pockets — was made of concentrated broth and was a fixture for travelling. Oat cakes were easy to prepare, cheap, and high in calories. But there was one food that famously gave 18th-century travellers their strength and will to carry on.

Pemmican — the quintessential survival food — was first developed by Indigenous people and later adopted by colonists. This Native American staple food was made up of dried game meats, fat, and wild fruits. The ingredients were pulverized into patties resembling dense jerky and were able to last for the length of any journey; some accounts even claim that pemmican could last for 30 years.

2. Macaroni and cheese existed in the 18th century

Believe it or not, America's favorite comfort food existed way back in the 1700s. Back then, macaroni and cheese looked a bit different than the goopy, orange concoction from a cardboard box that we know and love today. Macaroni and cheese dates back to 14th-century Italy, but it wasn't until the later part of the 18th century that American colonists brought the recipe stateside.

Good ol' mac and cheese in America is sometimes mistakenly credited as Thomas Jefferson's doing, although historians trace the roots of the dish's presence in the states back to James Hemings, Jefferson's enslaved chef. Hemings was trained extensively in the art of French cooking, where butter and cheese are a fixture in almost every dish. After spending time in France, Hemings brought the dish back to America, giving it the chance to become one of America's favorite meals.

3. The first American cookbook was published in 1796

Amelia Simmons was the epicurean mind behind the nation's first official cookbook, "American Cookery," published in 1796. The 47-page book is still, to this day, one of America's most influential cookbooks and is single-handedly responsible for allowing food historians to dive deep into the cuisine of America's colonial period.

The vintage cookbook features recipes for period-specific dishes like tongue pie, lamb's head soup, and fowl smothered in oysters. The desserts in the book — like pumpkin pudding (the predecessor to the pumpkin pie of today), a spice cake known as Queen's Cake, and johnnycakes — have stood the test of time a bit better than the savory options. Most of the book's recipes were based on European dishes but utilized Native American ingredients, and would eventually be viewed as the start of the country's post-colonization unique culinary identity.

4. There was candy, but it was much different from the candy of today

Ironically, the origins of candy trace back to early medicine, when herbal remedies were mixed with sugar to create tasty, healing treats. But by the 18th century, candy had transformed into something that was purely for the fun of eating stuff covered in sugar. Sweets were made up of ingredients like nuts, herbs, roots, bark, fruits, chocolate, and coffee. Candy was also a product of food preservation, where drying fruits and covering them in sugar allowed people to enjoy fruits when they would have otherwise been well past their prime.

Just like how we reserve candy canes for the Christmas season and candy corn for Halloween, the sugary treats of the 18th century were also seasonal, however, not necessarily by choice. Candy often changed throughout the year based on what fruits, herbs, or sugary ingredients were available during any given season.

5. People drank alcohol — a lot of alcohol

Ahh, good ol' booze. We love the stuff today, but folks in the 18th century really loved it. In colonial America, alcohol was consumed at just about double the country's modern rate. Men, women, and even children drank alcohol throughout the day, but it wasn't necessarily for fun. Fermenting juice was a convenient preservation method, and the plague-era tradition of consuming alcohol as a medicine made its way from Europe to America.

Juices made from native fruits were often fermented to create a sort of old-timey sangria, and rum from the West Indies was a popular choice for those who could get their hands on it. Beer, however, wasn't easy to come by, so it was an expensive luxury.

6. Dairy became a staple in the American diet in the late 1700s

Cattle were brought to North America by Columbus early on in its period of colonization in the late 15th century, but it wasn't until the later part of the 18th century that cow's milk started to become a staple for the settlers in the original colonies.

The production and distribution of cow's milk were largely for fertility purposes. Lactating mothers — both colonists and enslaved Black and Indigenous people — who were working and traveling had less time to breastfeed or were sometimes too weak to feed their children. Cow's milk filled that role, which started a practice that's still controversial to this day. Outside of feeding babies, cow's milk was also used for butter and cheese production, which would stay fresh without refrigeration for significantly longer than raw milk.

7. Colonists and indigenous people had wildly different diets depending on where they lived

Even today, where you live has a profound effect on your daily diet, whether your food is influenced by cultural traditions, native or seasonal ingredients, or both. In the 18th century, the foods that colonists and indigenous people ate were largely determined by where they lived and what was available to them.

Colonists brought edible plants and domestic animals to America from Europe, but they still had to supplement their diets with native foods. They crafted vastly different meals with different ingredients depending on their European country of origin and whether they lived in New England, the lower colonies, or the South. The same went for the Indigenous people. Those in the Southeast ate pecans and corn, while the Native Americans of the Great Plains hunted bison, and those in the Southwestern part of the country foraged for cacti and pinon nuts.

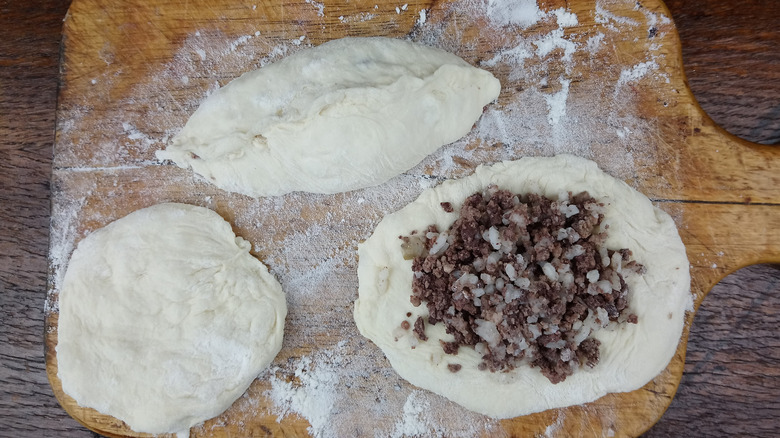

8. Mincemeat pies were ubiquitous

Meat was a staple for colonists, and one of the most convenient (not to mention delicious) ways to prepare and eat meat, and other ingredients native to the region, was as a mincemeat pie. Mincemeat pies actually date way back to medieval Europe, with colonists Americanizing their old family recipes when they got to the New World.

Mincemeat pies consisted of game or domesticated meats, suet, sweetened dried fruits, spices (both native and imported), alcohol, and herbs. They were a great way to combine a variety of staple foods into a portable, handheld meal that was nutritious and calorie-dense. The pies stayed fresh for months because the alcohol and sugar helped preserve them, so they were popular come wintertime, with mincemeat cow tongue pie being a luxurious Thanksgiving treat.

9. Drying was the predominant method of food preservation

We really take for granted the modern ability to preserve food for lengthy periods of time, while back in the 18th century, folks had to get creative if they wanted their food — which they worked so hard for — to last even a few days. There were multiple common methods of food preservation, but drying food was the simplest and most prevalent way to ensure that meats, grains, veggies, and fruits wouldn't go to waste.

Immediately after harvesting, fresh produce was cut and laid out to dry in the sun under a thin net to keep insects away. If you're thinking that this feels familiar, you'd be right. Sun-drying is still a relatively prevalent practice today. Meats and fish were also sun-dried after being sliced thin so all of the moisture could evaporate. Sometimes, thin-sliced meat was dried over a low fire, giving it a smoky flavor much like modern-day jerky.

10. Meat was king, while seafood was for the fishes

You'd think that living on the Eastern Seaboard, colonists would have been expert fishermen, eating highly nutritious fish and shellfish for nearly every meal. As it turns out, they weren't big fish fans and generally only ate fish about once a week.

250 years ago, most people ate primarily to fill their bellies and get enough calories and nutrients to tackle the day, rather than eating just for the fun of it, like we do today. And, ultimately, meat was heartier, more filling, and more calorie-dense. For colonists, stuffing pigs full of food scraps until they were large enough to slaughter and eat was easier than hopping on a fishing boat and setting sail, only to potentially come back empty-handed or with just a few shrimpy, if you will, shellfish to munch on.

11. Settler colonialism had a profound effect on Native American foodways

Nowadays, most of us are well aware of the devastating effects that settler colonialism has had on the Indigenous populations of the Americas. However, it's worth taking a glimpse into one specific, pivotal aspect of their way of life that was completely upended: their food.

By the 18th century, the presence of colonists proved to have lasting consequences on Indigenous foodways. Settlers seized vital agricultural sites from Native Americans, forcing them to rapidly adjust their food cultivation and foraging practices to be able to provide for themselves. Meanwhile, forced assimilation further distanced them from their longstanding food traditions. By the 18th century, colonists had also begun hunting the game animals that Indigenous people relied on until they were nearly extinct.

12. Passenger pigeons were eaten to extinction

When we think of pigeons today, we think of goofy birds walking along city streets or carrier pigeons travelling with handwritten messages. But in colonial times, a pigeon was only one thing: a delicious meal. The passenger pigeon was once endemic to North America, resembling the pigeons that we know (and are annoyed by) today. But settlers — using British high-society recipes — hunted and cooked the humble passenger pigeon until the last one in existence died in 1914.

In the 18th century, pigeons were the poultry of choice. They were roasted, baked, and boiled, just like our modern day turkey or chicken recipes. But, most famously, pigeon meat was put to use in a bougie, savory pie of English origins.

13. During a late-century wheat shortage, wheat substitutes were used to make bread

In the 1700s, wheat was in high demand. Wheat imported from England was the biggest export crop, specifically in the lower colonies. But a boom in England's population at the end of the century resulted in a significant shortage of this mainstay ingredient. Bread was a major part of colonists' diets, so instead of eliminating bread from their diets, they got creative.

Long before gluten-free foods were a hot topic, colonists were baking bread with different types of flour, many of which we still use today. Peas, oats, barley, corn, and buckwheat were ground up into flour to produce bread instead of wheat. Those lucky enough to have a bit of wheat might have added ground potato or turnip to their flour to stretch out their supply.

14. Stew was a staple for every meal

There's nothing like a comforting stew to warm you up on a chilly winter night. In the 1700s, however, stew was more than just a winter warmer; it was the most convenient, diverse, and safe-to-eat dish, with the ability to incorporate nearly every staple ingredient found in settlers' diets.

Stews were typically made from meat — either beef, pork, mutton, or game meats — with seasonal vegetables, herbs, and spices. It was sometimes eaten for every meal of the day, especially in the colder months. A hot stew was easy to keep safe from bacteria, with some families leaving a stew on all day or making a huge batch (like old-timey meal prepping) to reheat later, killing off any harmful pathogens that may have formed.

15. Ketchup existed in the 18th century, but it didn't feature tomatoes

When we think of colonial-era foods, highly processed, bright red ketchup may be one of the last things to come to mind. Tomatoes were thought of as poisonous by 18th-century settlers, since they're relatives of nightshade, so they wouldn't touch the stuff. Before folks learned the truth and tomato ketchup started to appear in cookbooks in the early 19th century, colonists made their condiment of choice with an unlikely ingredient: mushrooms.

Mushroom ketchup was made with salt, vinegar, lemon, spices, herbs, and wild mushrooms. The ingredients were left overnight and then stewed over a fire, creating a wonderfully bright, savory, and earthy flavor, completely unlike the sweet, tangy ketchup of today. Mushroom ketchup was used in a wide variety of savory recipes and was a convenient, portable seasoning that was particularly popular with soldiers of the time period.

16. Pickling was a common practice

Pickles are one of the rare foods that have been around seemingly forever, and aren't likely to go anywhere anytime soon. The practice of pickling is thought to have started all the way back in at least 2400 B.C. in ancient Mesopotamia. Since the practice is simple enough and excellent at preserving food, it wasn't uncommon to find pickled vegetables, fish, meats, and even fruits and herbs (but not garlic, which was only used for medicinal purposes at the time) in the homes of 18th-century colonists.

Whole meals were often made from things like pickled beef and vegetables, which could stay fresh in sealed jars for months, even years, on end. Meats and fish were typically preserved in a salt brine in large wooden barrels, while fruits were kept in jars with sweetened, seasoned vinegar. Even food scraps, like watermelon rinds, were pickled.

17. Without plenty of game meats, colonization might not have been possible

Colonists who were new to the North American continent in the 1700s weren't always what you'd call experts in foraging and identifying native, edible plants. They were, however, more likely to be well-versed in the art of hunting. In the time period, meat was an exceptionally popular ingredient in nearly every meal, both in Europe and America, especially come wintertime when it was easiest to preserve.

Since the first settlers arrived in the New World, and well into the 18th century, many types of game meat were the lifeblood of the colonists, even after hog and cow breeding became a common practice. Abundant wild game meats like squirrel, birds, rabbit, and venison — and even animals we don't typically eat today, like bear, moose, otter, fox, and raccoon — sustained the population of the 13 colonies to such a degree that they likely wouldn't have survived on wild and cultivated plants alone.

18. A millennium-old energy drink was popular in 1700s America

Sometimes water just doesn't cut it. In the 18th century (and even hundreds and hundreds of years earlier), a drink was invented to replenish the body and mind after toiling in the hot sun, much like an old-timey energy drink. The drink was known as switchel, and some historians consider it to be of New England origin, while others insist it came to us from the Caribbean islands.

Different versions of the potassium-heavy drink are thought to have been consumed all over the world. But the general recipe popular in North America in the 18th century consisted of water, either molasses or maple syrup, apple cider vinegar or citrus juice, and powdered ginger. Sometimes, folks would take this drink to the next level and toss in a splash of rum.

19. Indigenous people influenced the culinary traditions of 18th century settlers

Most colonists didn't arrive in America with any knowledge of what plants and animals they'd encounter, or how to cultivate this land that was so different from their home countries. Some foods existed in North America in the 1700s that we know and love today, but colonists were apprehensive about shellfish that washed up on shore and certain herbs, fungi, and fruits, thinking they were dirty or poisonous. They were dependent on the Indigenous population's extensive knowledge of the local fauna and flora and their trade offerings for their survival.

By the 1700s, they had established trade relationships with some Native tribes, who also showed the colonists what native foods were safe and plentiful and which were toxic. They taught them which native crops to plant — most notably corn, beans, and squash, which were staples known as "the three sisters" — to enrich the soil and increase their harvest yield.