The 10 Most Overrated Liquor Brands

As a professional bartender with years of behind-the-bar experience, I've tasted, mixed, and served my fair share of spirits — from obscure craft distilleries to globally recognized icons. Over time, I've noticed a recurring pattern: certain brands achieve fame, hype, or luxury pricing that their actual liquid rarely justifies. That's what I mean by "overrated." For the purposes of this article, an overrated brand is one that is sought-after, valued, or frequently discussed, yet, in terms of aroma, flavor, or overall drinking experience, fails to live up to its popularity, demand, or price point.

Being overrated doesn't automatically mean a spirit is bad. Many of these brands are technically well-made and can be enjoyable in moderation or in cocktails. The issue lies in the gap between perception and reality — between the story, marketing, or celebrity association and the sensory experience in the glass. Some are smoothed or engineered for mass appeal, some benefit from scarcity or celebrity cachet, and others have simply become luxury trophies rather than drinks meant to be appreciated.

In this article, I'll break down a range of liquor brands — from whiskey and gin to rum and vodka — that, despite their notoriety or cult following, consistently fail to justify the attention, acclaim, or price they command.

Aviation American Gin

Aviation American Gin is overrated not because it is bad, but because it is far more famous than it is distinctive. Its rise has less to do with what's in the bottle than with how neatly it fit into a cultural moment: the early-2000s craft-spirits boom, followed by a celebrity-branding era that turned Ryan Reynolds into the face of a product that already existed.

Aviation's "New Western" style and framing — positioning itself as a softer, more approachable alternative to juniper-forward London Dry – sounds radical on paper, but in practice it often translates to a gin that feels deliberately noncommittal. The lavender, citrus, and subtle spice are pleasant, yet they blur together into a profile designed not to offend rather than to intrigue.

In cocktails, this neutrality becomes more obvious. A gin that recedes politely into a gin and tonic or Negroni may be crowd-friendly, but it rarely leaves a lasting impression. Where more characterful gins assert themselves through pine, pepper, or bright citrus oils, Aviation tends to dissolve into the mix, offering smoothness at the expense of identity. That tradeoff might suit casual drinkers, but it hardly justifies the brand's reputation as a modern classic. Ultimately, Aviation is a triumph of branding and timing more than of distillation — a perfectly serviceable gin that has been elevated, largely by narrative, into something it never quite proves itself to be.

Grey Goose

Grey Goose is overrated for much the same reason it became famous: it perfected the illusion of luxury in a category that, by design, is supposed to be neutral. When it launched in the late 1990s, the idea of a "super-premium" vodka felt novel, and Grey Goose wrapped itself in the language of French wheat, pristine spring water, and Cognac-style craft. But vodka, stripped of character by definition, leaves very little room for those distinctions to actually show up in the glass. What you are mostly paying for is a story.

Blind tastings have repeatedly shown that many far cheaper vodkas perform just as well, if not better, on measures of smoothness and cleanliness – the very qualities Grey Goose claims as its calling card. Its texture is fine, its burn modest, but there is nothing about it that meaningfully separates it from solid mid-shelf brands made with the same modern column-distillation technology.

What Grey Goose truly mastered was signaling: the frosted bottle, the elegant goose, the aspirational bar placement. It became shorthand for "premium vodka" in clubs and cocktail lounges, even though the liquid itself is engineered to be as anonymous as possible. In a market now crowded with well-made, honestly priced vodkas, Grey Goose feels less like a benchmark and more like a relic of a marketing era that consumers have largely outgrown.

WhistlePig

WhistlePig is overrated not because it ever lacked quality, but because it is still trading on a reputation built from whiskey it no longer makes. When the brand launched, the late Dave Pickerell sourced extraordinary rye from Alberta – what many insiders still consider some of the finest rye whiskey ever distilled. That liquid did the heavy lifting. It was bold, spicy, beautifully structured, and it gave WhistlePig instant credibility in a market that was starving for serious American rye. The problem is that those original stocks are long gone.

What remains is a business model that hasn't meaningfully changed: buy Canadian distilled rye, blend it with other ryes from undisclosed sources, age it further in WhistlePig's own barrels and warehouses, then bottle it with a hefty markup. But extra aging doesn't automatically mean improvement. In WhistlePig's case, it often means too much wood — oak that smothers the bright grain and peppery snap that made the original whiskey special. The result can feel heavier, flatter, and less expressive than the Canadian rye it started as. Yet the prices keep climbing, buoyed by a legacy that no longer matches the liquid. Today, WhistlePig often delivers an inferior version of Alberta premium at a luxury price point, selling nostalgia and scarcity more convincingly than it sells whiskey.

St-Germain

While St-Germain certainly does not lack charm, it's overrated because it became a crutch. When the elderflower liqueur launched in 2007, bartenders quickly embraced it as an elegant, European-leaning flavor enhancer — an easy way to add perfume, lift, and a suggestion of botanical complexity to almost any cocktail. For a while, it felt revelatory, The problem was that its very versatility led to relentless overuse. Soon, everything from spritzes to sours to Champagne cocktails tasted faintly, and sometimes overwhelmingly, of that same soft white-flower sweetness.

That sweetness is where St-Germain shows its limits. Its floral aroma is indeed delicate and pretty, but the palate is much richer and more sugary than its branding suggests. In mixed drinks, it often crowds out more nuanced ingredients, flattening cocktails into variations on the same perfumed theme. What was meant to be a highlight becomes a blur.

There's also a practical flaw lurking behind the romance: St-Germain is not entirely shelf-stable. Because it's made from fresh elderflowers, its flavor degrades over time, meaning that an older bottle can taste dull, cooked, or oddly muted — hardly what you want from something priced and marketed as a premium liqueur. In the end, St-Germain is best used sparingly, but its reputation was built on excess.

Patrón

Patrón is overrated not because it lacks competence or cultural impact, but because its price and prestige no longer reflect what's actually in the bottle. Founded in 1989 and sold to Bacardi in 2019, Patrón helped define what "premium" tequila meant to a generation of American drinkers. It was also a pioneer of transparency, boldly putting "100% puro de agave" on its labels at a time when mixtos still dominated shelves. For bartenders, the brand has been unusually supportive, hosting competition and education programs at its Guadalajara hacienda that genuinely helped elevate tequila's standing in cocktail culture.

But today Patrón is also the third-largest tequila producer on the planet, moving roughly 3.5 million nine-liter cases a year. At that scale, romance gives way to logistics. Industrial efficiency, not artisanal nuance, becomes the priority — and that inevitably shows in the glass. While the tequila is clean and technically sound, it rarely justifies the luxury-tier tequila price it commands.

There's also lingering controversy over whether Patrón is truly additive-free, an issue that matters more and more to serious agave drinkers seeking transparency beyond marketing language. In a market now crowded with smaller, more expressive tequilas at similar or lower prices, Patrón feels less like a benchmark and more like a beautifully branded relic of tequila's first big boom.

Johnnie Walker Blue Label

From its inception, Johnnie Walker Blue Label was designed for the high-end gift market — not to be great Scotch in the traditional sense. Indeed, it was engineered to be a great luxury product: something smooth, impressive, and universally palatable enough that anyone with money, whether or not they actually liked whisky, could feel confident pouring it. That goal shapes everything about the blend. It avoids smoke, avoids sharpness, avoids idiosyncrasy. What you get instead is a carefully polished profile of soft malt, honeyed sweetness, and gentle oak that slides across the palate without ever demanding much attention.

For seasoned Scotch drinkers, that inoffensiveness is precisely the problem. Whisky's deepest pleasures tend to come from character — peat, coastal salinity, funky sherry casks, or the tension between spirit and wood. Blue Label sands those edges away in pursuit of elegance, leaving something that is undeniably smooth but also strangely hollow. It's luxury without risk.

The price compounds the issue. At a cost that could buy multiple single malts with real personality and age statements, Blue Label offers neither transparency nor terroir, just a vague promise of rare components and prestige packaging. It's a bottle meant to impress on a shelf or at a boardroom toast, not to reward curiosity in a glass.

The Macallan

Once celebrated for its rich, sherry-forward house style, The Macallan helped define what many drinkers think of as "classic" Speyside – deep dried fruit, baking spice, and polished oak. But over the past two decades, as demand for prestige single malt exploded, the distillery pivoted hard toward the high-end collectible market, with prices rising far faster than the quality in the bottle. That trend is precisely what makes Macallan overrated.

Let me clear: Macallan doesn't make bad whisky, but it has become better at selling luxury than at delivering proportionate value. Age statements quietly disappeared, replaced by vague, marketing-heavy ranges built around cask types and color codes. The whisky itself is often excellent, but rarely exceptional enough to justify four figure price tags. Heavy reliance on sherry-seasoned oak, while undeniably flavorful, can also flatten nuance, burying distillate character under layers of sweet wood and raisiny gloss. What once felt opulent now sometimes feels engineered.

More importantly, Macallan's dominance distorts the category. It trains consumers to equate expensive with great, even when smaller distilleries are producing more expressive, more transparent, and often better-aged whiskies for a fraction of the cost. In that sense, Macallan isn't just overpriced — it's emblematic of a luxury-first mindset that has drifted away from what made single malt compelling in the first place: character, craft, and sense of place rather than a sense of status.

Bulleit

Bulleit is overrated largely because its reputation is built on image rather than depth. Founded in 1987, it has become one of the fastest-growing whiskeys in America, a rise driven less by what's in the glass than by what's on the shelf. The frontier-style bottle, bold label, and Western mythology do a lot of heavy lifting, signaling rugged authenticity even though the whiskey itself is mass-produced and designed for broad appeal.

That design shows up in the flavor. Bulleit isn't unpleasant, but it is strikingly unremarkable. The bourbon leans smooth and sweet up front, with caramel and vanilla dominating, yet it rarely develops into anything more interesting. Instead of unfolding with spice, fruit, and oak in balance, it tends to feel one-note, then oddly sharp on the finish. That lack of complexity makes it a dull sipper and a frustrating mixer: without enough spice or structural backbone, it either disappears in a cocktail or contributes a blunt alcoholic edge rather than real character.

In a market crowded with bourbons offering genuine nuance at similar prices, Bulleit's popularity feels out of proportion to its quality. It succeeds as a brand far more than it does as a whiskey, and that disconnect is what ultimately makes it overrated.

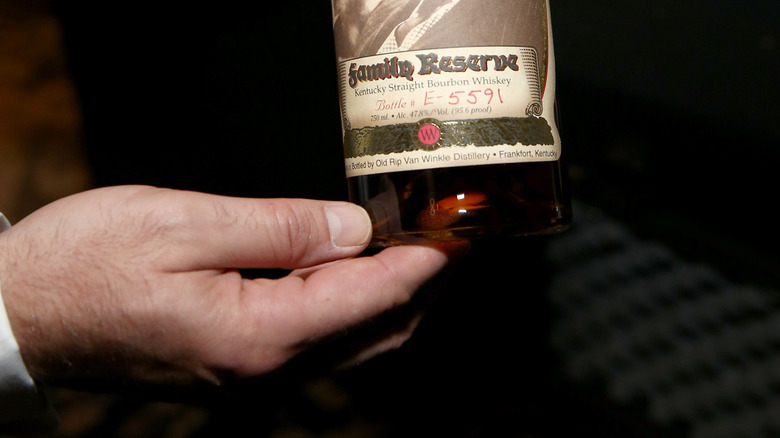

Pappy Van Winkle

At this point, Pappy Van Winkle is more myth than whiskey. There's no denying that the bourbon itself is very good – wheated mash bills, long aging, and careful blending can produce rich, soft, beautifully layered spirits. But the gap between that quality and the frenzy surrounding the bottles has grown absurd. Pappy is now treated less like a drink and more like a financial instrument, traded, hoarded, and flexed in ways that have little to do with what it actually tastes like.

At retail, it was once priced as a premium but still approachable bourbon. On the secondary market, it now commands thousands of dollars, a valuation that no liquid, however well made, can reasonably justify. Blind tastings often reveal the uncomfortable truth: plenty of far more available bourbons — some from the same distillery — can match or even surpass Pappy in balance, depth, and sheer drinkability.

The cult also distorts how people experience it. When a pour costs more than a weekend getaway, expectations become impossible to meet. Every sip has to feel transcendent, and when it doesn't, disappointment is quietly rationalized away. Pappy remains excellent whiskey, but its reputation has outpaced reality, turning something meant to be enjoyed into a luxury trophy that overshadows the simple pleasure of drinking well-made bourbon.

Bumbu

Bumbu rum is overrated because its hype outpaces what's actually in the bottle. Celebrity ownership – Lil Wayne's name attached to the brand – has helped it gain attention far beyond its merits, turning marketing into a bigger draw than flavor. On the palate, Bumbu leans intensely sweet, to the point of bordering on cloying, which has led critics to compare it more to a liqueur than a traditional rum. For a spirit that trades on Caribbean authenticity, that sweetness can feel artificial and one-dimensional.

There are further reasons for skepticism. Bumbu Original is bottled as just 35% ABV, well below the 40% standard for most rums, which diminishes both its presence in cocktails and its structural balance. Additives and flavor extracts, while creating an easy-drinking profile, further highlight that this is a flavored or engineered product rather than a nuanced, well-aged rum. Despite a relatively modest price tag, these factors combined make it feel overpriced for what it delivers: sugar, style, and celebrity cachet rather than craft or complexity. In short, Bumbu excels at image and approachability, but those qualities mask a rum that is often sweet, thin, and engineered — making its reputation larger than the liquid itself.