10 Vintage Airline Menus That Put Today's Snacks To Shame

We'd never be ones to complain about free food, but the snacks you get on flights today are so pitiful you start to wonder if they were always so drab and dismal. And in fact, they weren't. Long before our current era of miniature pretzels and measly cookies, airlines used to serve multi-course meals — sometimes even full buffets – on par with what you'd find on a cruise ship. They weren't just limited to meals; these airlines had menus with several choices for what to eat, unlike the modern choice between "cardboard" and "vegan cardboard."

So why was the food so much better back then? During the "Golden Age" of air travel, around the 1950s through the 1970s, ticket prices were heavily regulated by the government. Airlines couldn't undercut each other on price, so instead they competed on experience. Elaborate meals became an important part of airline's marketing strategies. Carriers like Pan Am, often considered the most glamorous airline, partnered with top restaurants to create elevated menus worthy of a first-class dining room. Passengers dressed up to the nines, white-gloved flight attendants plated meals and poured champagne in the aisles, and some aircrafts even had onboard lounges where travelers could sip cocktails or smoke after dinner. Dining in the skies was a luxurious and novel event.

Of course, that luxury came with a price. A round-trip ticket from New York to London cost about $300 in 1964 – roughly $3,200 today when adjusted for inflation. Air travel is far more accessible now, and that's something to be grateful for... but when you compare today's snack packs with yesterday's lobster thermidor, it's hard not to feel a little nostalgic.

Air Union served the world's first full-course in-flight meal.

While the first documented meal served on an airplane dates back to 1919 (cold sandwiches served on a London-to-Paris flight), it would take nearly a decade for airlines to attempt something more ambitious. The breakthrough moment came on July 30, 1927, when a French company, Air Union, served what is widely considered the world's first full-course, in-flight meal. And "full-course" wasn't an exaggeration. Passengers were presented with hors d'oeuvres, lobster salad, cold chicken and ham, salade niçoise, ice cream, and a cheese-and-fruit finish. Drinks were equally impressive, ranging from champagne and wine to whisky, mineral water, and coffee. By today's standards, the 1927 lineup still seems like a meal fit for a banquet hall.

This moment was a milestone in commercial aviation, but Air Union's lavish service didn't last long. Within two years, the airline discontinued the service, deeming it too impractical to sustain. Yet its influence lingered long afterwards. By the 1930s, aircraft were being constructed with onboard kitchens, allowing meals to be heated in newly designed convection ovens. Later on, airlines adopted frozen meals, an innovation made possible by food-technology research developed during World War II. While frozen meals don't sound too glamorous today, they dramatically expanded what could be served in the air and helped pave the way for the elaborate, multi-course menus that would define the glory days of in-flight food.

Pan Am's first-class menu was catered by Maxim's Paris.

In the 1950s, flying first-class on Pan Am's Boeing 377 Stratocruiser meant stepping into a world of elegance and glamour, and nowhere was that more evident than in their food selection. The menus from this era are designed with curling ribbons and charming mid-century illustrations, and they prominently feature the logo of Maxim's Paris, a legendary French restaurant. For years, Maxim's chefs handled all of Pan Am's catering for transatlantic flights. Meals were prepared in Paris, flash-frozen, and shipped to storage locations around the world so passengers could enjoy haute cuisine at cruising altitude.

The menu offered all the greatest hits of classic French dining, starting with martinis, sherry, and Manhattans served with canapés. The first course featured consommé double, followed by boeuf braisé bourgeoise, Vichy carrots and pommes Anna (all served with red and white wine, of course). The meal concluded with a plate of assorted cheeses, fresh raspberries, and finally coffee, tea, cognac, or a selection of liqueurs.

Maxim's is still open today, and is considered one of the most beautiful restaurants in the world. Famous for its Art Nouveau decor and timeless Parisian fare, it offers a glimpse of the culinary culture that once followed passengers all the way into the sky.

Pan Am's economy-class meal was equally impressive.

In the early 1950s, Pan Am became the first international airline to introduce a lower-fare alternative to first class. Originally called "tourist class," it would evolve into what we would call "economy" or "coach" today. Since all ticket prices were regulated by the government in those days, Pan Am lobbied the International Air Transport Association to approve a reduced-service model, which included smaller seats and an abridged meal service. One requirement for the "tourist" experience was that meals had to be served cold to clearly differentiate it from the hot, multicourse service served in first class.

By the early 1960s, a typical Pan Am economy meal arrived as a partially assembled tray: bread, salad, and dessert already in place, with flight attendants serving the tray from a cart. As economy travel skyrocketed in popularity after its introduction, Pan Am began to serve complete meal trays.

Menus were still surprisingly generous by today's standards. A mid-1960s economy menu included cream of tomato soup, fricassée de veau à l'ancienne, pilaf rice with peas, salad, dessert, and coffee or tea. And despite the lower fare, economy passengers weren't eating with flimsy plastic cutlery. They still used real silverware, and their trays, plates, and bowls were made of heavy-duty plastic designed for repeated use. Even the presentation was a far cry from the disposable trays we're familiar with today.

Air France served a distinctly stylish French dinner.

In-flight dining reached new heights throughout the 1960s, with each airline reflecting its country's culinary style. Air France served a menu worthy of a five-star restaurant: medallions of foie gras truffé, river trout en gelée, grilled racks of lamb, and veal paupiette with mushrooms. Side dishes included pommes au gratin, Clamart artichokes, Andalouse salad, and of course, a traditional plateau du fromage to finish. Dessert was just as extravagant: bombe glacée followed by a fresh fruit basket. Drinks ranged from apéritifs and champagne to an assortment of French wines, cognac, liqueurs, and fruit eau-de-vie. It was a full-blown haute cuisine experience, crafted specially to showcase France's culinary prestige.

Despite the high cost of tickets, air travel was becoming relatively more accessible by the '60s. By 1961, a round-trip ticket from Paris to New York cost roughly one-third of what it had in 1956, opening the market to more passengers than ever before. Air France embraced the new wave of air travel with style. In the early 1960s, their flight attendants wore uniforms designed by Christian Dior; later on in the decade, Cristobal Balenciaga took over their designs. And from 1966 onward, passengers enjoyed another luxury we take for granted today: the in-flight movie. It's hard to imagine a transatlantic journey without one, but back then, it was a cutting-edge marvel.

Northwest Orent Airlines served their dinner with complimentary cigarettes.

On a Seattle-to-Tokyo-to-Hong Kong flight in 1966, Northwest Orient Airlines offered passengers a sophisticated dining experience in tandem with a distinctly mid-century pastime: in-flight smoking. The menu began with assorted cold hors d'oeuvres and a seafood cocktail, followed by an entrée choice of New York strip steak with marchand de vin or a filet of salmon. Side dishes included braised celery hearts or broiled tomato Provençale, along with marinated artichoke hearts dressed in creamy Italian dressing. Passengers also enjoyed dinner rolls with butter, assorted pastries, a fresh fruit basket, and a selection of cheeses with breads. The beverage service featured apéritifs, cocktails, whiskies, chilled champagne, and French and American wines... and lastly, complementary cigarettes to end the meal.

In the early days of air travel, smoking in the cabin was a standard practice. Flying was a luxury experience, and cigarettes, along with copious amounts of alcohol, were seen as just another part of the dining experience. Flight attendants routinely offered cigarettes as part of their service throughout the '60s. It wasn't until the 1970s that growing concerns over second-hand smoke began to change perceptions. By the late 1980s, bans on in-flight smoking were gradually introduced on domestic and short flights, culminating in a complete ban on all domestic and international flights to and from the United States by 2000. Today, the "No Smoking" neon signs on airplanes are a reminder of that not-so-distant chapter of air travel history.

Pam Am's breakfast menu was simple but fresh.

Dinner wasn't the only extravagant meal served in-flight. On a 1966 Pan Am flight from Tokyo to San Francisco, passengers awoke to a breakfast menu charmingly titled The President Special: Petit Déjeuner, printed in both English and Japanese. Even as a morning meal, it showcased Pan Am's signature refinement and commitment to international service during the height of the Golden Age of air travel.

The menu began with chilled juice and fresh fruit, followed by an assortment of cereals served with fresh cream. Hot dishes included three styles of eggs — fried, scrambled, or boiled — paired with hickory-smoked ham and sausages. Warm rolls with butter and jam rounded out the meal, along with a choice of coffee, tea, or hot chocolate. While it was simpler than some of Pan Am's famously elaborate dinner services, it was still far more generous than the modest breakfast boxes handed out on most long-haul flights today. And the fact that it featured real eggs, real tableware, and a fully plated presentation put it miles above what most airline passengers are served now.

Trans World Airline offered international-themed flights.

By the late 1960s, airlines were competing fiercely to stand out from one another. Few marketing tactics were as theatrical as Trans World Airline's "Foreign Accent Service." Launched in 1968, this program aimed to bring an international flair to TWA's domestic long-haul routes, such as New York to Los Angeles. Each flight embraced a specific theme – French, Italian, British, or American – and everything from the menu to the cabin's atmosphere was tailored to match. To complete the experience, flight attendants wore themed costumes made entirely from paper, slipping into them before takeoff and tossing them in the trash once the flight ended.

For the British-themed flight, everything was styled to be reminiscent of Ye Olde England. The drinks section of the menu, titled "From the Innkeeper's Cellar," included a choice of whiskies, Scotch, a "mug of ale," and even "Drambuie, the liqueur of Bonnie Prince Charles." For the food options, listed under "The Day's Offerings," passengers chose from a surprisingly robust lineup: deviled lobster, pub-style; an "Empire" salad with assorted breads; and a range of mains including grilled filet steak, brisket of beef Carnaby, broiled Windsor-style lamb chop, grilled Dover sole Kensington, or curried chicken Bombay. For these flights, flight attendants wore frilly collars to match the theme.

United served steak and lobster on domestic flights.

Elaborate meals weren't soley reserved for international flights. A 1969 menu from a United flight from San Francisco to Detroit is just as lavish as Pan Am's international offerings. The drinks list alone covered bourbon, Scotch, and Canadian whiskies, plus an extensive cocktail selection: the "United Airlines Special," dry martinis, old fashioneds, Manhattans, daiquiris, Bloody Marys, Spanish sherry, gin, vodka, beer, tomato juice, and various soft drinks. Hawaiian macadamia nuts were served as an accompaniment.

Dinner began with a poached quenelle of scallops in Nantua sauce. For the main course, passengers could choose from broiled filet mignon with berry sauce, scaloppini of veal sauté au Marsala, minced chicken with mushrooms and berry sauce, baked langostinos Thermidor, or a stuffed baked potato with buttered Mexican corn. Rolls and salads were served on the side. The dessert menu included pistachio meringue glacé, mandarine sherbet, a hot fudge sundae, or petits fours, served with coffee, Sanka, tea, or milk, and finished with a dinner mint.

If you're wondering how steaks were cooked in-flight, a common method was to cut, trim, and freeze the steaks before being loaded onboard. They were then cooked to order on electronically heated quartz grills, which could bring a steak from frozen to rare or well-done in just seven minutes.

Japan Airlines charged 25 cents for beer and sake.

Japan Airlines' 1970 menu was relatively restricted compared to the grandeur of some '60s-era airlines, printed mostly in black-and-white and listed with English and Japanese text. Dinner began with a seafood cocktail, followed by tournedos with Italian sauce, served alongside buttered potatoes. A seasonal salad with French dressing and a mandarin pudding for dessert rounded out the meal, accompanied by rolls, butter, and a choice of coffee, tea, or green tea.

A separate snack menu offered a surprisingly generous spread: fruit compote, a poached egg on tomato, boneless ham, salami sausage, cheese, and raisin bread, plus coffee, tea, or milk. These menus were slightly unusual compared to others from the '60s because alcoholic beverages weren't included in the fare. Cocktails, whisky, gin, and vodka were priced at $0.50, while beer and sake were just $0.25. At today's prices, that would be $4.00 and $2.00 respectively.

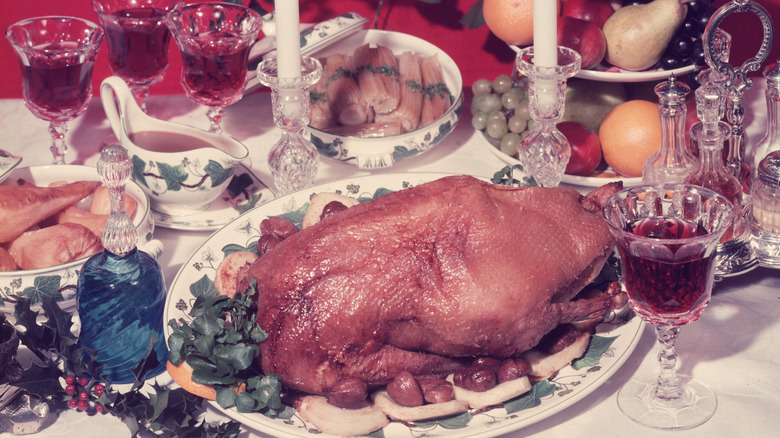

Pan Am served a full Christmas dinner in the 1980s.

The 1980s unfortunately marked the final full decade of Pan Am's operations. Following the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 and a series of poorly timed business decisions, the once-dominant airline found itself at a significant disadvantage heading into the '80s. Passengers were increasingly looking for affordable flights, not the elaborate international experiences that had defined Pan Am's service for decades.

Yet the airline stubbornly maintained its reputation for luxury. One example is its Christmas dinner menu, which offered a feast of festive elegance above the clouds. The holiday spread began with egg nog and a tossed garden salad, followed by a choice of roast turkey Grand Veneur with chestnut dressing and cranberry sauce, accompanied by buttered vegetables and candied sweet potatoes, or broiled filet mignon maître d'hôtel with a stuffed baked potato and jardinière vegetables. The meal concluded with a holiday dessert and a selection of beverages, including coffee, tea, red and white wines, champagne, and liqueurs.

Even as the airline struggled financially, Pan Am's dedication to presentation, variety, and service remained intact. Its meals during this period were a final flourish of the glamour and sophistication that had once made Pan Am synonymous with international air travel.