10 Bizarre And Disturbing Facts About Nutmeg

Nutmeg: you've probably cooked with this warm, sweet, and cozy spice before when making a béchamel sauce or a batch of eggnog without giving it a second thought. A readily available and affordable spice, a small bag of ground nutmeg at the grocery store costs a few bucks and lasts for years. But beneath its aroma and taste lies a history that's anything but warm and fuzzy.

For centuries, nutmeg was a luxury worth killing for. Its value sparked brutal colonization, massacres, and international espionage. Though not nutritionally essential, spices like nutmeg transformed bland European dishes, and as a result, became incredibly expensive ingredients. As one of the rarest spices, nutmeg was worth its weight in gold and prized by royalty as a symbol of wealth and power.

Nutmeg is also a bit of a biological oddity. The ground nutmeg you find in your pantry is far removed from its original form and origin, and contains a compound called myristicin, which can cause hallucinations in large doses. Throughout its long usage in the world, nutmeg has been used as medicine, a hallucinogenic, and even for magic and good fortune. Keep reading to uncover the stranger-than-fiction story of one of the world's most powerful and peculiar spices.

Nutmeg is not a nut

The word "nutmeg" comes from the Latin "nux muscata," meaning "musky nut," but don't let the name fool you: Nutmeg isn't actually a nut. It's a seed that comes from the fruit of the Myristica fragrans, a tropical evergreen tree that can grow up to 40 feet tall. The fruit itself is shaped like a small apricot or peach. When it ripens, it splits open to reveal a glossy brown seed wrapped in a vivid red, lacy covering. The brown seed is nutmeg. The red part surrounding it is mace — no, not the stuff you spray in someone's eyes. This kind of mace is a warm and sweet spice that, when dried and ground up, is used in curry powders and garam masala.

Not only does this tree produce two kinds of spices, but the fruit itself can be eaten too. Though it's largely unknown in Western cuisine, nutmeg fruit is popular in places where it naturally grows, like Indonesia. The taste of the raw nutmeg fruit is both citrusy and spicy; it's said to taste like a lemon rind sprinkled with nutmeg. It's often made into candies, juices, pickles, and essential oils.

Meanwhile, the nutmeg we're familiar with has already been transported across continents and arrives in supermarkets as either whole nutmeg or a finely ground brown powder. Grated fresh nutmeg is more potent than the grounds, so be cautious when substituting it in your recipes.

Nutmeg's origin was kept secret for hundreds of years

Nutmeg originally comes from a set of volcanic islands in one of the most remote corners of Earth. The Banda Islands, part of the Maluku archipelago in Indonesia, are tiny volcanic specks of land located thousands of miles away from Jakarta. Of the 11 islands in the chain, only five naturally have nutmeg trees. For most of world history, these islands were the world's only source of nutmeg and mace.

The remoteness of nutmeg made it incredibly valuable, to the point where the islands' location was a closely guarded secret. By the 6th century, Arab merchants were selling nutmeg in Constantinople, and around the 12th century, they began selling it to Europeans in Venice. But absolutely no one in Europe knew exactly where nutmeg came from. A small group of Arab traders guarded its origins closely for centuries and would even give faulty directions to European sailors to keep their prices high and outsiders out.

It wasn't until 1511, when Portuguese forces led by Afonso de Albuquerque captured a trading hub close to the Banda Islands, that European powers began closing in on the location of the so-called "Spice Islands." This would start an era of colonial forces dominating the region and the use of extreme measures to control the source of nutmeg.

Nutmeg used to be insanely expensive

When nutmeg reached Europe in the Middle Ages, it was much more than just a spice used in cooking. The imported commodity was one of the most expensive items in the known world. For much of Europe, it was a luxury reserved for the elite. Records show that the fare at a royal feast for the King and Queen of Scotland in 1256 was spiced with 2 pounds of nutmeg and mace, and 50 pounds of ginger and pepper. In 1476, the Duke of Bavaria's wedding feast called for a staggering 85 pounds of nutmeg. By the 14th century, a pound of nutmeg cost as much as "seven fat oxen," per one German price table. Later, in 18th-century London, the price of nutmeg was up to 90 shillings per pound; that's over $1,200 in U.S. currency today.

Nutmeg's prestige even inspired fashionable accessories. Wealthy Europeans carried personal nutmeg graters — tiny, ornate tools designed to add a dash of spice to drinks like punch at a moment's notice. These graters were first popularized by English elites in the 1600s as a status symbol. Today, those antique graters are highly valued collectibles. Thankfully, nutmeg itself is a lot more affordable.

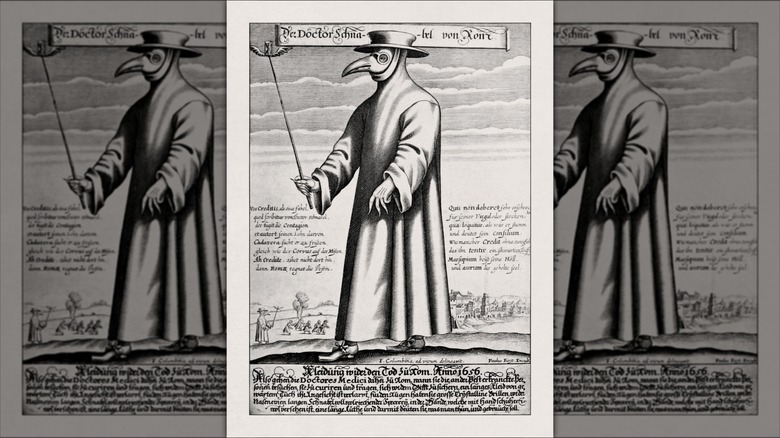

Nutmeg was believed to ward off the Black Death

In 14th-century Europe, people had more uses for nutmeg than just food; they were using it as a last-ditch weapon against the Black Death, too. At the time, most people subscribed to the miasma theory, or the belief that diseases were spread by bad smells in the air. As a result, people believed that strong, pleasant-smelling substances, like flowers or herbs and spices, could protect them against infection.

Nutmeg, with its strong aroma, was one of the elite contenders for getting rid of bad smells and fetched exorbitantly high prices at the time as a result. It was stuffed into plague doctors' masks alongside cinnamon and herbs to help "purify" the air. And ironically, nutmeg does have mild antibacterial and insecticidal properties, so it may have offered some tiny, accidental benefit by repelling fleas — the true carriers of the plague.

But in a cruel twist of fate, the very spice trade that brought nutmeg to Europe may have helped spread the disease further. Merchants and sailors arriving from the East were also unknowingly bringing rats aboard their ships, which in turn carried the infected fleas. In the end, the spice that people believed could protect them was arriving on ships that were helping the plague spread even more.

Nutmeg was a pivotal part of the spice trade, resulting in genocide and enslavement

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach the Banda Islands in the early 1500s, but they weren't the first outsiders to trade there. For centuries, people from China, Java, and across the islands region had visited these islands to exchange goods. When the Portuguese tried to muscle their way into the nutmeg trade, they were met with fierce resistance from the local Bandanese population. After a few decades of dealing with the hostility, the Portuguese gave up and left the islands.

However, things changed when the Dutch arrived toward the end of the 1500s. Already at war with Portugal and hungry for control of the spice trade, the Dutch had no interest in diplomacy. Instead, their solution was to kill and enslave the local population. In 1621, an estimated 14,000 of the Banda Islands' 15,000 inhabitants were either massacred, forced into slavery to work on Dutch-run nutmeg plantations, or escaped to nearby islands.

Even after this brutal and openly genocidal campaign, the Bandanese didn't disappear completely. After escaping to the Kei Islands, they maintained their own trading networks with neighboring islands for centuries afterward, quietly outlasting the Europeans' obsession with spice. Today, at least two Bandanese villages (the people of whom call themselves the Wandan) still exist in the Kei Islands, carrying on the language, culture, and legacy of the original people of the Banda Islands.

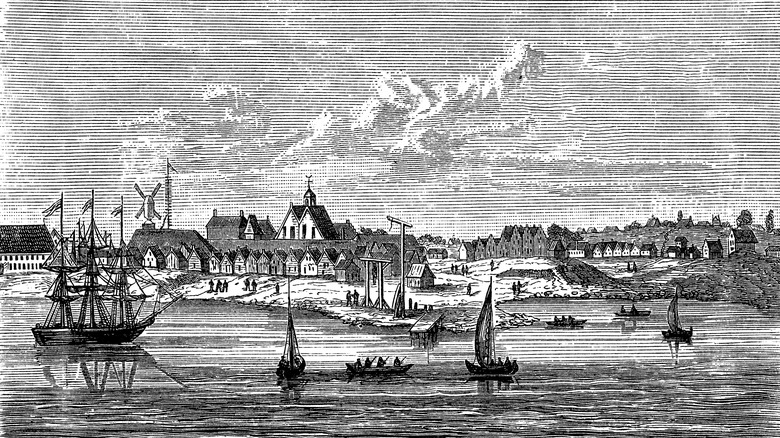

The Dutch traded New York for nutmeg

The Dutch initially arrived in the Banda Islands in 1599, eager to dominate the nutmeg trade. They were aggressive, and the Bandanese people were rightfully wary of trading or working with them. In 1603, hoping to push back against Dutch pressure, the Banda island of Run made a deal with the British instead: In exchange for protection and trade rights, the English could settle on their island and collect nutmeg. Run became one of Britain's very first overseas colonies.

This agreement kicked off more than 60 years of conflict between the Dutch and the British over the fate of this tiny island. In 1667, the two empires finally struck a deal. Under the Treaty of Breda, the Dutch would take full control of Run, and in exchange, the British would get a sleepy colonial outpost called New Amsterdam, soon to be renamed New York.

To the Dutch, giving up some swampy island in North America seemed like a fair price to finally secure their monopoly on nutmeg. Meanwhile, the British got a little island named Manhattan that would eventually become a massive international hub inside their new empire in America. Few trades in history have aged quite as dramatically as this one!

Nutmeg was democratized thanks to international plant smuggling

For over a century, the Dutch maintained a ruthless monopoly on nutmeg production in the Banda Islands, enforcing their control with deadly violence and making a fortune by keeping prices artificially high. However, at the same time, the French and the English were plotting their own schemes to topple the Dutch's reign and get their hands on nutmeg for themselves.

In the 18th century, a cunning entrepreneurial botanist and administrator known as Pierre Poivre was determined to grow nutmeg on the Isle de France (known as Mauritius today). Between 1768 and 1772, Poivre orchestrated secret expeditions to the Maluku Islands to smuggle nutmeg plants out under the radar. With the help of local spy networks, French agents snuck over 3,000 nutmeg plants off the islands and back to Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. It would take decades of experimentation to cultivate it, but eventually the smuggled nutmeg plants finally took root and successfully grew outside their native land for the first time.

Later, during the Napoleonic Wars of the 1800s, Britain very briefly took control of the Banda Islands. The Dutch kicked them out soon after, but not before the British grabbed nutmeg seedlings and quietly shipped them to their colonial territories, like Sri Lanka and Penang. Nutmeg cultivation had spread across the globe, and the Dutch monopoly was over at long last.

Nutmeg can get you high - or even kill you

It's not just an urban legend: Ingesting too much nutmeg can cause hallucinations, nausea, and even temporary psychosis. The two compounds responsible for the effect are myristicin and elemicin. These are naturally occurring chemicals that, when consumed together in large amounts, can seriously mess with your head. Myristicin is chemically similar to MDMA, while elemicin has been used in the synthesis of mescaline.

Thankfully, the teaspoon called for in most baking recipes is harmless. But according to toxicologists, ingesting two tablespoons or more can lead to a very unpleasant hallucinogenic experience. Symptoms include visual distortions, vomiting, dizziness, anxiety, and extreme drowsiness. Worse, the effects take several hours to kick in and can last for days, making it one of the worst trips imaginable. Nutmeg intoxication is rarely fatal (there are only two known deaths linked to it), but it can cause convulsions, heart palpitations, and serious discomfort.

Despite how awful it sounds, nutmeg has a history of being a desperate, last-ditch effort for people looking to get high. In the 20th century, it was reported to have been used in prisons, where access to other substances is obviously limited. But because of its horrific symptoms, it's not a commonly used drug for a reason. Just stick to a sprinkle of it in your next banana bread and you should be fine.

Nutmeg is believed to have medicinal and magical properties

Throughout its long history, nutmeg has been credited for its medicinal and even magical benefits. It's played a part in many traditional medicines across the globe, from Indian Ayurvedic medicine to folk medicine in Pakistan, Malaysia, and parts of Africa.

Modern science does back up a few of its health claims. Nutmeg contains powerful antioxidants, anti-inflammatory monoterpenes, and antibacterial compounds. Some studies suggest it may help with libido and mood, but only in small amounts. Too much, and you're risking a run-in with the hallucinatory side effects mentioned earlier.

Beyond medicine, nutmeg also shows up in folklore and magic across the globe. It's been carried by merchants as a good luck charm, believed to ward off evil, ensure safe travel, or bring financial success. Some of those superstitions might stem back to nutmeg's long history of trade, travel, and association with wealth.

Connecticut is called the Nutmeg State

Considering nutmeg's long, globe-spanning history, it might surprise you to learn that Connecticut's unofficial nickname is the Nutmeg State. The spice isn't native to North America, so why are people from Connecticut sometimes called "nutmeggers?"

Nutmeg has been used in American cooking since colonial times, and Connecticut merchants played a key role in importing the spice from Europe. One theory behind the nickname is that conniving Yankee traders would sell fake wooden nutmegs to unsuspecting buyers who didn't know what real nutmeg looked like. This might be why the phrase "wooden nutmeg" came to refer to a fraud or scam.

Another version of the story is less devious. Some buyers, unfamiliar with the spice, tried to crack whole nutmegs open like walnuts rather than grating them, leading them to believe they'd been sold a fake product. Whichever theory you believe, both offer a fittingly odd origin for Connecticut's quirky name. After all, when it comes to nutmeg, the story is never quite as simple as it seems.