Prohibition-Era Grape Juice Came With Instructions For Breaking The Law

Throughout America's notorious veto on alcohol, it was all about loopholes. Between speakeasies hidden behind unassuming storefronts (though there are still unique haunts worldwide today) and bathtub gin, creativity was at an all-time high. Many distilled their own lethal concoctions from home, while others sought approval from religious institutions for sacramental wine or pleaded for a whiskey prescription from their doctor. Just a few years into Prohibition, America discovered a legal way to flirt with the taboos, and everyone seemed to be in on it. The "grape brick" was a seemingly modest, concentrated grape juice block designed to make homemade juice, but it was also the secret to makeshift wine.

The temperance movement didn't just ban alcohol sales. Prohibition hurt the U.S. by making everything surrounding alcohol illegal, including making it, drinking it, gifting it, and even supplying possible ingredients. Shady business practices were a dime a dozen, but a particularly ingenious one came from vineyards that were suddenly out of work. While they couldn't legally produce wine, they could sell non-alcoholic wine (grape juice) and leave the last wine-making steps up to the consumer. It came with specific instructions on how to avoid making wine, but in doing so, they subtly provided all of the steps to fermenting a nice red. The coy packaging was littered with warnings, essentially informing consumers that this brick was practically wine, so if you weren't careful, you might "accidentally" end up with a bottle.

Grape bricks helped keep vineyards afloat during Prohibition

Vino Sano was one of the first grape brick labels on the market, produced by a San Francisco-based vineyard. Some just went ahead and called them "wine bricks," as the intent was universally understood. But the Vino Sano brick instructions were framed as negatives, including directives such as: don't dissolve the brick in a gallon of water, don't add sugar, don't shake daily, and definitely don't decant the juice after three weeks. If followed, these steps conveniently produced a 13% alcohol by volume wine. Another tell was the blatant wine-centric flavors. The $2 bricks shamelessly came in sherry, Champagne, port, claret, or muscatel, as Time reported in 1931.

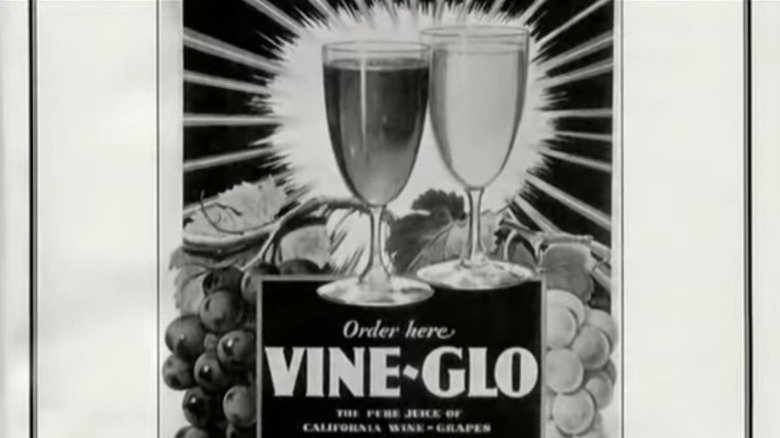

Vino Sano seemed to kick off the innovative scheme, but many other producers dabbled in non-alcoholic beverages that were suspiciously similar to the early steps of wine-making. Vine-Glo was even less subtle, with full wine glasses right on its label. The vineyardists were sure to include the legality of the "juice" as thoroughly as possible, and in the biggest, boldest letters. "For home use only" and "legal in your home" were printed front and center, and even included the specifics of the law they were skirting (Section 29, National Prohibition Act). While there were legal ways to get alcohol during Prohibition, this one was an inventive, hands-on option.