A Diet Of Takeout Food Fueled Bonnie And Clyde's Infamous Rampage

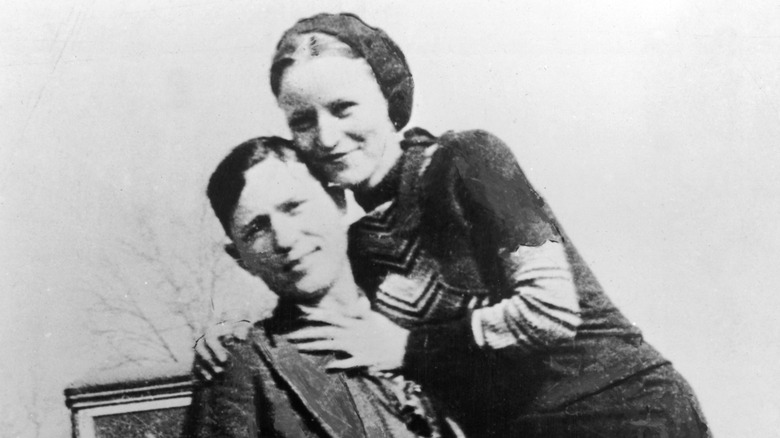

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow lived fast, died faster, and ate like fugitives the whole way down. Forget the movie myths of champagne toasts and candlelit steak; when you're changing hideouts twice a night, takeout is both strategy and sustenance. The Barrow gang ate what the road handed them, which was generally classic fried chicken wrapped in wax paper, bologna sandwiches, and whatever a gas station counter could cough up before the next siren. For Bonnie and Clyde, eating was mostly logistics: don't get recognized, don't get poisoned, don't get slowed down.

W.D. Jones, who ran with Bonnie and Clyde and survived long enough to dish to biographers, remembered meals as a catch-as-catch-can, grab-and-go affair — sandwiches if you were lucky, canned Vienna sausages or beans if you weren't. Sometimes it was nothing more than canned soup or day-old pie snatched from a dusty roadside café, eaten in the back of a stolen Ford. Their diet was built for speed. The convenience and calories mattered; taste (in both senses of the word) mattered less.

The couple's food routine was as practiced as a bank heist: pull in, order quick, eat in the car, and vanish before the faces behind the counter had time to match the headlines. The less time spent inside, the slimmer the chance of a bad break. Takeout joints and greasy spoons became anonymous waypoints on a map of robbery, running, and the fleeting comfort of a rare hot meal, composed of old-fashioned hot dogs roasted on a stick by the side of the road.

Bullets, lettuce, and tomato

Fried chicken was a favorite of the gang of ne'er-do-wells, partly because it could be eaten on the run and partly because nobody is going to ask why you're eating fried chicken in Texas. Even in the press, food dogged their story. In 1933, the gang drew unwanted attention in Platte City, Missouri, when Blanche Barrow marched into the bustling Red Crown Tavern to buy five fried chicken dinners, a tall order for a single woman, especially when she paid in small change pilfered from some vending machines. The staff took note of the unfamiliar face, the curious order, and the coin-heavy payment, and word got around, and an ambush and shootout with the law ensued. When you're living outside the law, even a quick meal could blow your cover.

On May 23, 1934, Bonnie and Clyde, America's most wanted, met their end not in a blazing gunfight at a bank, but outside a tiny Louisiana café run by Rosa "Ma" Canfield. Their final meal order, according to period accounts and museum records, was classic Depression-era road food fare: a BLT and a fried bologna sandwich, plus donuts and coffee. Local lore says someone reported the tellingly suspicious order, and either way, what we do know is that lawmen did set up another ambush seven miles outside town. When they opened fire, the star-crossed lovers (and their sandwiches) went down in a hail of bullets.

They died as they lived, eating fried food on the road. Today, tourists in Gibsland can order the same baloney sandwich at the old Ma Canfield's Café, now a part of the Bonnie and Clyde Ambush Museum, and chew over the idea that sometimes, it's not the stickup that gets you, but the takeout.