New York Restaurants Are Opening At A Surprisingly Fast Clip

New spots have lower rent and little buildout

Editor's Note: This article first appeared in Astrolabe, the excellent Substack newsletter on Michelin-starred restaurants from Gary He. You can subscribe here.

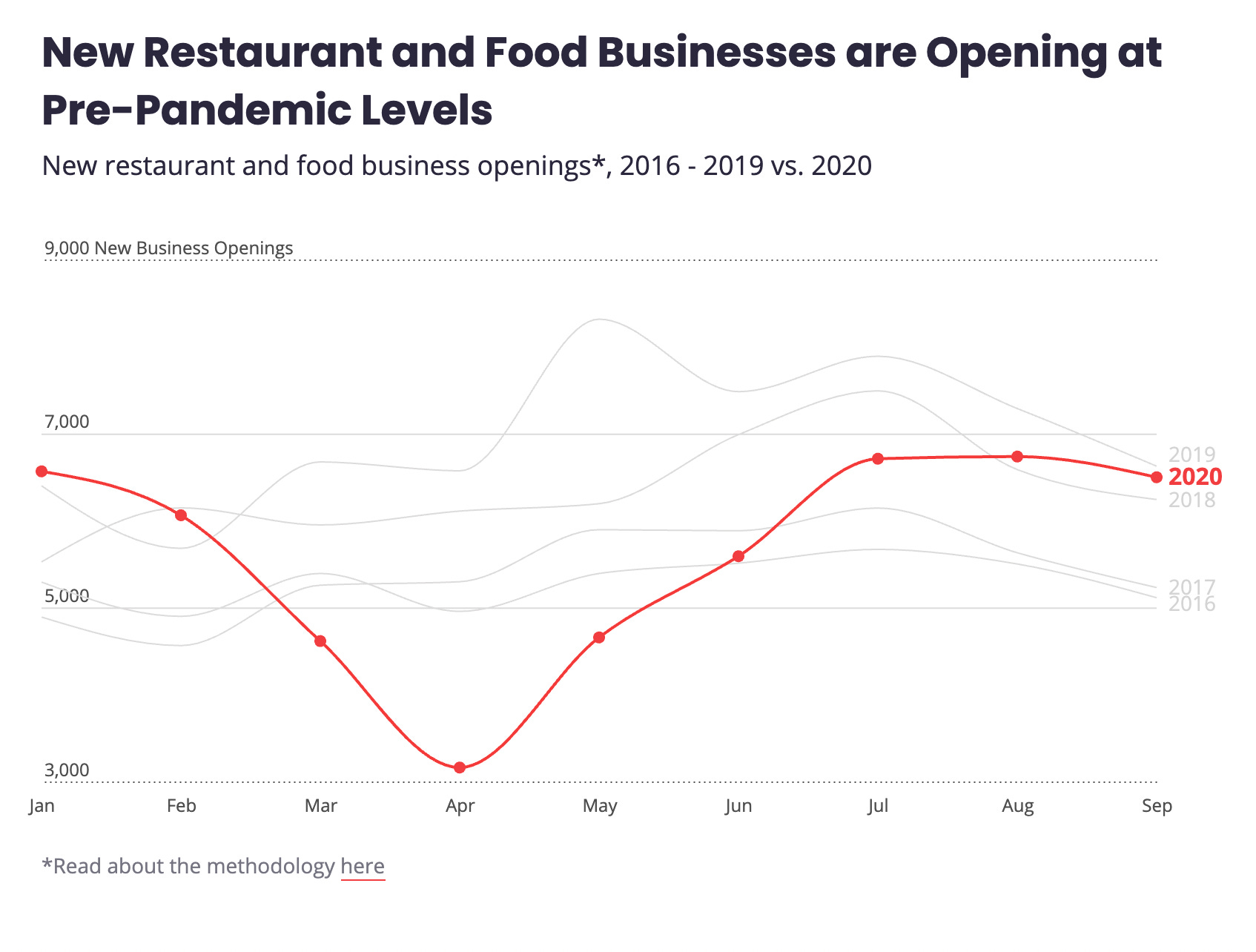

Nearly a year into the pandemic, restaurant spaces are turning over at almost pre-pandemic levels, according to Yelp's 2020 Annual Report, with new ones tailoring menus to the moment, moving into turnkey spaces, and taking advantage of rent deals.

After Michelin-starred Jewel Bako and Ukiyo shuttered in March, it didn't take long for 239 East 5th St. to become a new restaurant; in November, a young team installed by a meat wholesaler opened its first New York restaurant, J-Spec for "Japanese Specification" (by their admission, a made-up phrase). The menu focuses on Japanese wagyu imported by its parent company.

"We opened during the middle of the pandemic, and everyone said we were crazy," said Jumpei Sakai, the culinary director at Tomoe Food Services. Meanwhile, he's trying to spread the wagyu gospel with prices that are "cheaper than Costco."

The lease terms unequivocally drove Tomoe Food Services to snap up what had been Jewel Bako and Ukiyo: The first year's rent is $4,000 a month (a 50 percent discount) and they can exit any time without penalty. But there is another enticement: The restaurant would inherit the bones of successful, Michelin-starred restaurants. J-Spec did next to nothing to the space: It opened with the same Ukiyo mural and swapped out the nameplate. In all, Sakai estimates that he saved about half a million dollars in buildout costs, allowing him to be lean enough to launch a restaurant in the middle of the pandemic.

In New York State, according to the Yelp annual report, 2,548 new food and beverage businesses opened since early March, many of them taking advantage of turnkey situations created by recently closed restaurants and landlords looking to fill vacancies as quickly as possible in an uncertain market. Offerings border on fire sale-territory, with five months of free rent in one case to a year of heavily reduced rent in others. Sometimes the new tenants get both.

"Most landlords are eager to get spaces leased quickly," said James Famularo, president of Meridian Retail Leasing. Famularo's name and phone number adorn hundreds of former restaurants, the distinctive baby blue sign declaring "RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE" — an all too common sight in the city's pandemic landscape. He is bullish on New York (or at least he is when a journalist reaches out to him).

"There has never been a better time to get great deals on commercial spaces in Manhattan," said Famularo (who, as part of his job, hypes the New York City commercial real estate market).

Across town on University Place, John Fraser shut down his vegetarian joint Nix in June. But by August, vegan restaurant group Blossom cherry-picked the location because it didn't require many changes.

"If you take a restaurant that serves meat and fish and things like that, there's a lot more cleaning to do; it's a different energy in the kitchen," said Blossom restaurant co-founder and owner Ronen Seri, who confirmed he received half-off rent for the first year. "I wouldn't do this in any other place, honestly."

The lack of buildout costs combined with flexible escape clauses created an environment that is ripe for restaurateurs with a little cash to test new concepts or try a new neighborhood to see if it'll work. For this year, at least, the typical 10-year commercial lease is a bit less ironclad.

Peeking between cracks of papered windows at 7 Spring St., I spotted construction inside the former Uncle Boons space but was unable to determine who had taken over. (My calls to the landlord were not returned.) And at the former Bouley at Home on West 21st Street, giant posters bearing Famularo's name have been removed; he confirmed to me that there are several offers on the table.

"We are signing deals all over the city," said Famularo.

Despite all of these new openings, the reality is that we're still in the middle of a pandemic, and nobody is making money yet. Sakai noted that 50 percent capacity is the minimum to break even. "We're not looking for profit at the moment, only minimizing cash out the door."

But these new restaurants have low overhead, a bit of financial wiggle room, and may be better suited to survive months of operating at a loss.

As for the rent deals? There are sure to be many more: Indoor dining may be returning, but at 25 percent capacity, it is largely not profitable. Sales during the post-holiday period are usually dreadful for the industry, pandemic or not.

And the churn isn't going away. "A lot of restaurants will give up this winter," said Sakai.