Jacques Pépin Talks New Cookbook, Julia Child, And Biggest Cooking Disaster - Exclusive Interview

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

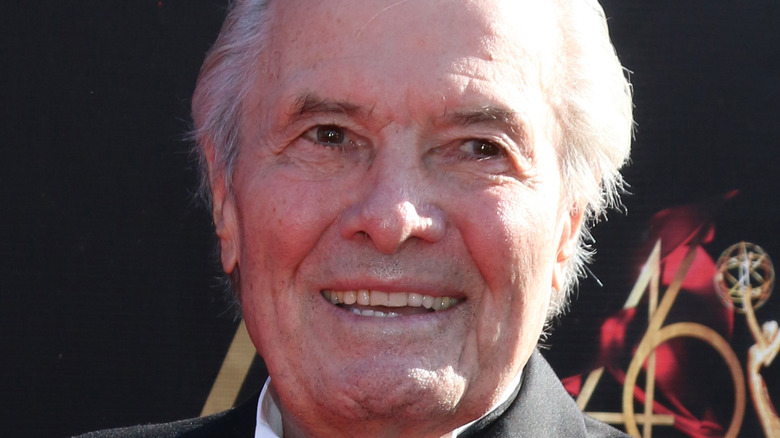

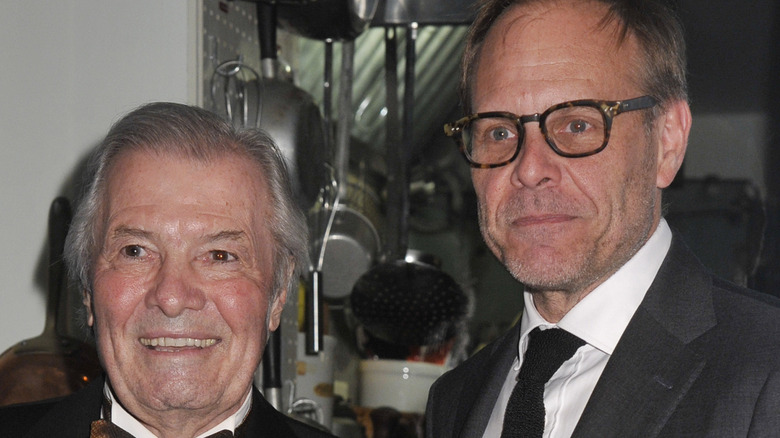

Jacques Pépin is a man who needs no introduction, but we'll give it a shot. After cooking for multiple heads of state in France as a young chef, he immigrated to America and started working at the now-legendary French restaurant Le Pavillon. That's already an illustrious cooking career, but the thing that has made Pépin a culinary icon is his commitment to education. He's authored over two dozen cookbooks, including the classic "La Technique" (via Art Net), and hosted a wide variety of cooking shows since the 1980s (via IMDb).

Jacques Pépin's new cookbook, "Art of the Chicken," is a little bit of a change of pace from his previous work. It has recipes, but it's also a memoir. Perhaps most importantly, it's a gallery of dozens of drawings and paintings of chickens that the chef has created over the years. Yes, in addition to his culinary mastery, Pépin is also quite proficient with a paintbrush. In an exclusive interview with Tasting Table, the chef talked about his love of chickens, his food philosophy, and his run-ins with other famous food personalities.

His artistic inspiration

What artists inspired you to take up painting?

I have been painting since the late '50s or early '60s. I've been painting forever, in my free time. I was married for 54 years. From the beginning, when we were married, we had a little house in the country. When people came for dinner, then we would write down the menu, whatever we ate, and people would sign on the other page and say funny things. We would put the label of the wine on it, [and] we would write even the music we played.

I illustrated the menus, and I realized I illustrated with chickens very often. I have 12 or 13 books of those menus, which is basically my whole life. My daughter came a few weeks ago, and she's now in her mid-50s. She said, "What did I eat for my third birthday?" I said, "Let's look," and we looked, and we found her, with all these chicken drawings. That was probably the beginning of what I do now.

If you could cook for one artist you love, who would you pick?

That's a good question ... probably Picasso. Yes, because of the diversity of what he did, from the blue period to abstract art.

Tips for buying and cooking chicken and eggs

You have access to great farm eggs a lot of the time. If you were giving advice to people who are shopping in a grocery store, what would you say to look for in chickens and eggs?

With eggs now, you can get organic eggs basically in any market, and the price is relatively inexpensive. A dozen eggs is [$3 to $5]. The organic ones [are about $1 to $2] more, so it's nothing, in terms of eggs. In terms of chicken, look at the organic chicken. It's also what you can afford. I will go for organic chicken usually, but if I go to my market and they're selling conventional chicken, and today you get two for one, I'll get those and put them in the freezer.

Are there any mistakes with cooking chicken that you see beginner cooks making a lot?

Drying it out too much, cooking it too much. Especially, the breast can get dry and overcook pretty fast. One way to cook it to avoid this is to use a very high temperature and let the bird rest or the pieces rest for a while after cooking so that the juice equalizes.

A whole section of the book is devoted to cooking things like liver. Lots of American cooks throw these pieces away. If somebody is cooking chicken offal, where would you tell them to start?

[Go with a] Jewish-style chicken liver mousse recipe, whether it's chicken or duck livers, with the liver and the fat of the chicken or the duck pureed together. At that point, it's emulsified too. [With] a dash of cognac or nothing at all, or salt and pepper, people will love it. You tell them what it is and it's a bit different. If you look at chicken feet, that's very good too, but they look like chicken feet so people get scared. The chicken mousse looks like a puree of something, so it's not that scary.

Would you serve it to people and have them try it, and then tell them what it is afterward?

Yes, sometimes. People will say, "What is that?" I say, "Taste it. You tell me what it is."

Mishaps with chicken embryos and Julia Child

One theme in the book is that, over your life, you've tried all of these chicken dishes that were new to you. The only egg dish you weren't able to eat was a raw chicken embryo in China. What did you do when you were face-to-face with the embryo and realized you weren't going to be able to eat it?

All the people in front of me were Chinese. They were breaking the egg, getting the embryo, dunking it in coarse salt, and swallowing it. I broke mine, took it out, dunked it in coarse salt, brought it to my nose, and I put it back. I couldn't swallow that one.

You mentioned that you shared many meals with Julia Child. Did you and her have different approaches to cooking chicken?

We had different approaches to cooking anything. We always argued and fought, but it was a good argument with a bottle of wine between us. I like kosher salt. She didn't like it. I like black pepper and she only liked white pepper, things like that which are not very important. We loved to argue and share wine.

She cut herself with your paring knife right before you were going to appear on a live TV appearance. How did you react when that happened?

It was in Los Angeles, at "The Tomorrow Show with Tom Snyder," and she brought all the food, so there was enough food for 50 people. With her, we never worried about recipes. We just cooked, and so that was great. We came on stage to check things out, five minutes before the show. I gave her that knife that I carried with me because I was on a book tour. At that time, you could carry a knife on the plane. She cut a piece off of the end of her finger, and I pushed it back together. She was mad at herself more than anything else.

She didn't want to talk about it on air, and Tom Snyder said, "Okay." As we opened the show, one of the first things he said was, "Would you mind if I tell people you cut your finger?" She wasn't happy, but on the other hand, it turned out that they did a sketch about her on "Saturday Night Live." It became a big deal too, so she enjoyed that part of it.

A cooking demonstration catastrophe

Did you ever have any mishaps or cuts while you were filming one of your shows?

Cooking is the art of recovery or adjustment or compensation. One time, I was doing a demonstration for 2,000 people in Sacramento on a big tour. It was the Go Natural tour, so there were dancers, there were singers, and there was one portion for cooking, which was me. I did a cheese soufflé. I appeared in about half of the show. They calculated about 40 minutes before the end of the show so that I could go back on stage and retrieve the soufflé from the oven at the end. It was a question of timing.

I came on stage and I looked at the stove. Everything was working. I looked at the oven. I did my soufflé, put it into the oven and left, and didn't come back for 40 minutes. Unbeknownst to me, the oven went on self-cleaning, like 750 degrees or whatever it was. You've never seen a soufflé as black and as burned as mine. I had a standing ovation, practically.

Was the oven filled with smoke when you opened the door?

Yes. There was no recovery there.

How his cooking has changed over the years

During the pandemic lockdowns, you made many at-home cooking videos that were very useful for people who were stuck cooking at home. Did spending more time in your house change your approach to the kitchen at all?

Not really. I always cook at home, every day. It wasn't really much of a change except as you get older, your cooking changes — more simplified. Now, I have beautiful tomatoes from my garden, and that's all I need. When you are a young chef, very often you tend to add to the plate. Now that I'm older, I remove from the plate to be left with something more essential without too many embellishments. The type of cuisine that I did in the videos was usually very simple things with what I had in my refrigerator or freezer or out of the garden, recipes that took three [to] five minutes to help people cook at home.

Do you think there's more honesty in that simple approach to cooking?

I don't think that there is a question of honesty. You'll have the same type of honesty in very sophisticated cooking. It's a question of approach and where you are. If you go to eat at Per Se in New York or at Daniel, where you expect to have very fancy dishes and calculated plates, that's what you go there for. It's a different situation. One is not really better than the other. It's different.

You left home to work as a culinary apprentice when you were 13 and never looked back. Was it scary to start your professional life at such an early age?

Not at all. It was very exciting. Since I was five or six, I'd been in the kitchen with my mother. I had two brothers, and my mother had a little restaurant, so it's not like we didn't work. We'd get there to peel potatoes or wash the bottles from the cellar or do one thing or another. Leaving and getting into an apprenticeship for me was something very exciting.

Life was very simple, in a sense, at that time, over 80 years ago. My father was a cabinetmaker by trade, and my mother did a little restaurant cooking. We didn't have the television, we didn't have a radio, we didn't have the telephone, no books. I had blinders on my eyes. I was going to be a cabinetmaker or a cook; that was about it. I went into the restaurant business, and I was very excited about it.

Why you should cook with your kids early

Do you have any advice for people who want to cook with their kids?

You cannot have the kid eat pizza or some type of takeout food when they're little while you cook a rack of lamb and then, at age 10 or 12, try to put the kid at the table and make them eat like you. You cannot do that. You've got to feed them the same food you eat when the kid is a year old, as soon as they start eating. When my daughter was a child, I don't think we ever bought baby food. I cooked spaghetti or whatever I had (I cut down on the salt and all of that), and then I took some of it to put in the blender to make a puree out of it. The kid was used to those tastes from the beginning.

When the kid always works in the kitchen, that's crucial. I held my daughter when she was a year and a half old and then made her stir the pot so she "made it," so she was going to eat it, and likewise with my granddaughter. She came and sat next to me at the stove. She was [between three and six] years old. I said, "Okay, give me the salad. You think it's clean? Okay, let's go to the garden, let's get some parsley."

I said, "No, let's try it, taste it, that's parsley. Give me that tomato. You think that tomato is ripe? Smell it. You think it's ripe?" The kid gets involved, touches the food, and that establishes a platform for communication, in a sense. After, the beauty of it is that you share the food at the table. It has to be done from the time the kid is born.

The two kinds of omelet

The final chapter of your book is devoted to eggs, and one of the most famous cooking segments of you is a video where you make both a country French omelet and a more haute cuisine omelet. If you had to pick between the two, would you pick the country omelet or the fancier one?

Sometimes I would pick one, sometimes I would pick the other, depending what I'm in the mood for, whether I have a hangover or not, it's hot or not, whether it's humid or not, [or] what's my mood.

A classic French omelet as I do is not better than the country one, it's just different in technique, in texture, and in taste a little bit, so you choose one or the other. Some people like their eggs very well cooked and some pretty wet in the center. It's a question of taste again, but the idea is to expose yourself to it, to expose the kid to it, and to share the food.

Old vs. new styles of culinary education

When you came up in the kitchen and were training, you worked in kitchens with the classic brigade system and chefs who were all-powerful. Now, things aren't so formal. What are the advantages and disadvantages of how you were trained versus the modern style?

It's a question of age. I've taught at Boston University for over 40 years now, and I was the dean at the French Culinary Institute in New York. In those places, a lot of people started cooking in their mid-20s or later. They went to college. Some of them were doctors or lawyers too, and at 40 years old, they decided to change and become a cook.

It's a totally different way of teaching people like this than when you're 13 years old. When you're 13 years old, the chef says, "Do that," and you never question. And if you say, "Why?" he would say, "Because I told you," and that was the end of it. In my first year or two of apprenticeship, I never approached the stove except to fill it up with wood and coal and clean it.

All of a sudden, chef said, "Okay, you start at the stove tomorrow." My God, I never thought that I would know how to do it. You learn through osmosis in a different way, by repeating, and the chef says, "You do this, do that," you repeat, you repeat, and eventually, you work at the stove. That's probably a good way, to a certain extent, to teach someone who is [12 to 15] years old, which is different from someone 30 years old. There is good and bad in both ways of teaching.

Stories from the French presidential kitchen

You were [French President] Charles de Gaulle's chef for a little bit in the '50s. What were some of the de Gaulle's family favorite things to eat?

When you cook for the presidents — I served [prime minister of India Jawaharlal] Nehru, [Yugoslavian dictator Josip] Tito, those were the heads of state at the time — you work with a protocol, usually, depending on whether the dinner is long, short, two meat, one meat, and so forth, [also] depending on the dietary requirements of the guests. You're not going to serve a pork chop to the prime minister of Israel.

However, on the normal days, and certainly on Sundays, the de Gaulles were very devout Catholics who, after church, always had family dinner with children and grandchildren. I always made the menu with Madame de Gaulle and then did whatever they wanted. At that point, she wanted everything a certain way, she wanted a leg of lamb, but not too rare because it's not good for the president, and some type of fish. You cook to please and to make people happy. It would be a different type of cooking, what we would do for state dinners and what we would do for them when they were by themselves.

There's a story that you once rode in the presidential car to go buy bread.

I used to take care of the Secret Service and people like that who were always coming into the kitchen to get something to eat and drink, so they were nice to me if I needed to go somewhere. One day, I needed to get bread fast, and so they gave me a car with the siren and all that to go there [and] get bread. That was a fun memory.

The rise of celebrity chefs

When you moved to the US, you were offered a position to cook for John F. Kennedy, but you turned it down. Was the White House shocked that you didn't want to go cook for the president?

No, I don't really think that they cared one way or the other. I had already been chef to presidents, different ones in France, between '56 and '58. At the time, I never had an interview with a magazine or a newspaper. Television barely existed. Being a famous cook, that never existed. The cook was really at the bottom of the social scale, and any good mother would have wanted her kid to marry a lawyer or a doctor, not a cook. It was a different world.

When I was asked to go to the White House, to tell you the truth, at that time, I didn't realize the potential because that sort of food celebrity never existed before. I had been in New York already for a while, and I was used to it. I had friends, I was going to Columbia, so I didn't really want to move again.

Now, there are so many chefs who are celebrities. You were at the forefront that movement. Do you think it's a positive change that so many chefs are famous now?

Absolutely, as long as the chef doesn't take it too seriously. If you are 20 years old, you've been cooking for four, five years, and someone writes an article on you and says you're a genius ... if you believe it, then you're in trouble. You can't take it too seriously, but we are not where we used to be, at the bottom of the social scale. It's much better.

James Beard and the joys of free wine

You ate at Chez Panisse with James Beard as your dining companion in the '70s. Did you realize at the time what an important and revolutionary restaurant that would turn out to be?

Not really. It was Jeremiah Tower who was the chef at the time, and they'd just started. I thought that it was like I was back in France eating very straightforward, simple, easy food that you used to have in restaurants like my mother's. I loved it, but didn't realize what it would become.

How did James Beard like his chicken?

James Beard was a glutton. He'd eat anything — just like me, I guess.

You talk a lot in the book about drinking wine while cooking and eating chicken. Do you have specific wines you like to drink with chicken and egg dishes?

The ones I like the best are usually free wines. I'll drink any of those.

Jacques Pépin's "Art of the Chicken" goes on sale September 27. Pre-order the book here.

This interview has been edited for clarity.