The History Of Tamales, One Of The World's Oldest Recipes

Legend says that the first tamales were made from the flesh of a god. The Aztecs believed that Tzitzimitl, grandmother of the god Chicomexóchitl, created the first tamales. Tzitzimitl sacrificed her grandson to create the tamales; the first corn sprouted from his grave. While archeologists have yet to discover evidence that the first tamales were created by a god, records do suggest they may date back 10,000 years — making them one of the oldest dishes still eaten today. These early tamales even predate corn: They were made from teocintle, the plant that would later become corn.

You might expect one of the world's oldest recipes to be straightforward, but tamales are remarkably labor-intensive. To make tamales, ancient cooks treated corn kernels with an alkali solution to break down the tough cell walls and bind the dough together. This process, called nixtamalization, made the backbreaking work of grinding corn a little easier. But cooks still have to prepare fillings and dough, wrap the tamales, and tend to them for hours while they cook. It's hard work, especially with traditional tools.

For ancient Mezoamericans, the pros outweighed the cons. Tamales served a practical purpose: Hunters and soldiers carried the nutritious, filling, and easily portable cakes with them while away from home, sort of like an ancient cliff bar. Over time, tamales evolved from an on-the-go snack to a culturally significant dish, served at feasts and employed in religious rituals. Tamales have changed over time — but also stayed the same.

Tamales in pre-Columbian cultures

For the Aztecs, tamales were a key part of religious celebrations with special recipes for different festivals. For the festival of the jaguar god Tezcatlipoca, the Aztecs stuffed tamales with beans and chiles; shrimp and chile tamales were served to celebrate the fire god Huehueteotl. Tamales played a key part in weddings and funerals, and they were offered to the poor during the Great Feast of the Lords.

On special occasions, pre-Columbian cultures folded tamale wrappers into elaborate shapes and decked the tamales out with designs made from flowers and seeds. A well-decorated tamale was seen as the hallmark of a skilled craftswoman, on par with sculptors and painters.

While pork and beef are some of the most popular tamale fillings today, the tradition only dates back a few hundred years: Pigs and cows were first introduced by European colonizers. Pre-Columbian cooks had no shortage of fillings, though. They used meat from deer, axolotl, rabbit, turkey, armadillo, fish, and frogs; they flavored their tamales with chilis, tomatoes, beans, flowers, and mushrooms. Tamales weren't limited to savory flavors, honey and fruits were also used.

Like many aspects of local culture, the Spanish tried to quash tamales. They attempted to replace corn flour with flour made from wheat, but it proved impossible to rid the culture of a staple that had persisted for so long. Tamales didn't disappear, they evolved — incorporating new flavors from Europe along the way.

Tamales in Mexico

While European colonizers wiped away many ancient traditions, tamales are still integral to nearly every major Mexican holiday. Tamales are served on the Day of the Dead, on weddings and birthdays, at New Year celebrations, and on Christmas. Many Mexican families prepare for Christmas with a tamalada, or tamale-making party. Family members travel for the event as tamales are prepared in shifts or assembly lines.

Mexico is home to over 500 distinct types of tamales — but, given how food transforms over time, from cook to cook and household to household, the actual number could be near infinite. The Huastec region of Mexico is known for the zacahuil, sometimes called the "party tamale." Zacahuil takes its name from the Mayan word for "big bite," an apt name for a tamale that ranges from 1 to 5 meters long and feeds 50 to 150 people.

Today, tamales are a source of pride and national identity, celebrated with festivals and events. But, for many years, they were eschewed as low class, even morally reprobate. Wealthy Mexicans opted for European cuisine, at least in polite society. But tamales persisted — not only among the lower classes but also as a guilty pleasure for the elites. In the late 19th century, the Mexican Revolution brought a new sense of pride in traditional culture. Mexican society began not only to accept but to celebrate the culture, and tamales with it.

Tamales in Central and South America

Tamales are found throughout Central and South America, from the Amazon to the Andes, and vary accordingly. A version known as pamonhas are popular in Brazil. Pamonhas are often served sweet, made from corn mixed with sugar and coconut — a combination introduced by the African cooks who influenced local cuisine. Brazilians eat pamonhas to celebrate Festa Junina, the Brazilian harvest festival.

In Guatemala, "red" tamales are stuffed with pork, chicken, olives, peppers, and tomato; "black" tamales blend meat with sweeter fixings like chocolate, raisins, and prunes. Nicaraguans eat nacatamal for breakfast, a tamale wrapped in banana leaves and often stuffed with meat, tomatoes, potatoes, and mint.

Many Caribbean countries have their own tamale traditions. Dominicans make pasteles en hoja, a type of tamale made with plantains and root vegetables instead of corn. Rather than wrapping masa around a meat filling, Cubans chop up meat and mix it into the dough.

These variations are often based on history or geography. Some are influenced by other cultures, like Brazilian pamonhas. Others employ ingredients local to the regional climate: Mountains, arid deserts, and rainforests. But throughout both Central and South America — and into North America, too — tamales serve as a thread that connects disparate peoples and cultures to a deeper history.

Tamales in the United States

Traditionally, tamales didn't stop north of what is now known as Mexico. Several Native American tribes ate variations of their own. The Choctaw made a version called banaha, and bean bread — a tamale-like, corn-wrapped bean patty — was popular among the Cherokee.

In the Mississippi Delta, tamales eventually became part of African American cuisine. Some people say that they were brought home by soldiers returning from the Mexican-American war, other accounts claim that tamales were introduced to the area by migrant cotton harvesters from Mexico. These recipes developed into hot tamales, a heavily-seasoned variation that uses corn meal instead of masa.

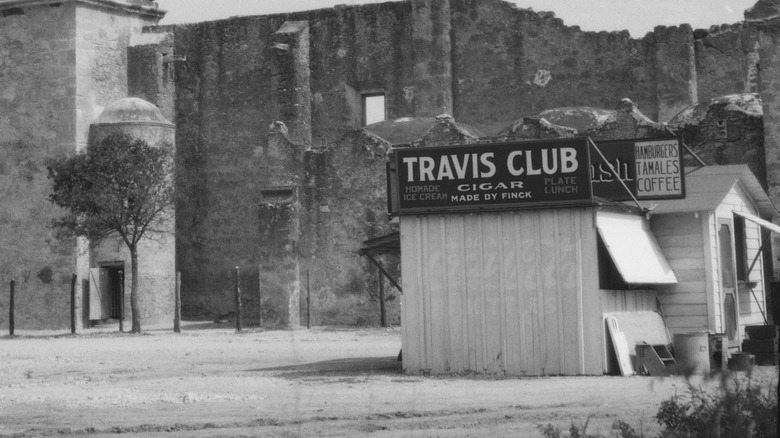

It wasn't until the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, that tamales really took off in the United States. While visiting Californians, who were already familiar with tamales, weren't impressed, the broader American public loved them. Soon, tamales could be found on street corners across America. These tamale stalls inspired both bloody turf fights — the infamous tamale wars — and popular music. The tamale craze of the 1920s inspired songs like "Here Comes the Hot Tamale Man" and Robert Johnson's "They're Red Hot," which modern audiences might know thanks to covers by both Eric Clapton and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

While many tamales sold in America bear little resemblance to traditional Latine cuisine, they offer first-generation chefs an opportunity to explore their heritage. Latine chefs make carrot cake tamales and hot dog tamales with American cheese, pushing the culture — and cuisine — in new directions.