What Viking Funerary Flatbread Teaches Archeologists About Ancient Baking

When most people think of the Vikings, they probably envision what the Vikings did way before picturing what they ate. But if food is fuel, then it's safe to say that the nomadic and infamously chaotic lifestyle of the Vikings needed lots of it. Most of what culinary archaeologists know about the Viking diet has been compiled from a combination of dig sites, the foods eaten by heroes in Norse sagas, and even a limited selection of ancient cookbooks. The Vikings as a people left behind precious few records and accounts. But one momentous archeological dig site uncovered a historical gem: Viking Funerary flatbread.

The loaves were uncovered in graves at Birka — a large, formerly hopping Viking trading post near Stockholm — earning this flatbread the name "Birka bread". Miraculously, the loaves were charred and therefore remained preserved through time. Whether the loaves were intentionally charred as a culinary choice or if they were burned in funeral pyres remains unclear.

The flatbread loaves found at Birka were made from a simple combination of salt, eggs, and flour, specifically barley and wheat. Other types of Viking bread used oats or spelt flour. For closest replication, curious home cooks should make their Birka bread over a campfire. But today's foodies don't value the loaves just for their recipe; the bread tells a much larger story than the sum of its parts.

Loaves centuries in the making

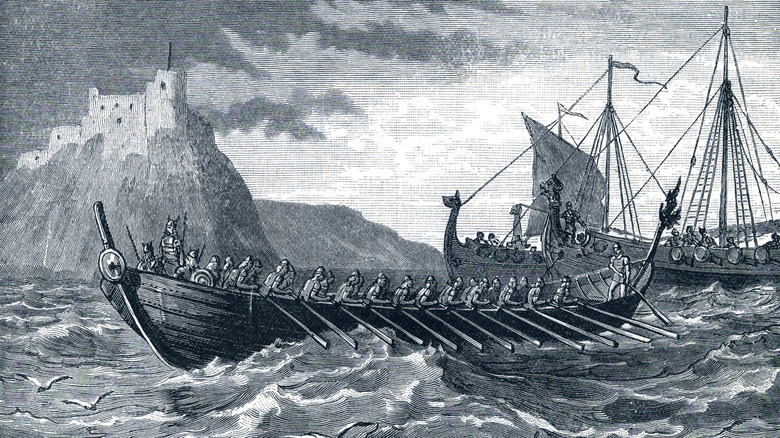

Crafting a loaf of flatbread was no small feat for medieval home cooks — but the passage to the afterlife was no small matter to the Vikings. Viking funerals typically involved cremation via elaborate pyres constructed on boats or rafts. In polytheistic Norse mythology, boats represent a safe passage into the world of the afterlife. (Whether these funerary boats were actually sent out to sea seems less likely than popular lore would suggest.) Unfortunately for modern historians, these cremations left behind little in the way of artifacts. Vikings were buried with an assortment of gifts known as grave goods, ranging from weapons to jewelry and food to sustain them on their journey to the next world.

Fittingly, creating the funerary flatbread was a production in itself. The grain would have been harvested pre-technology, likely with an ard, a plow consisting of a small wooden spike attached to an ox cart steered by a farmer. There weren't even any scythes in this region of the world yet. To make matters even more complicated, Northern Europe had short growing seasons with minimal sunlight, rocky land, and drastically varying levels of elevation. Today, a traditional bread with a similar recipe is still made in Normandy, France. Indeed, Normandy was originally settled by a group of Norsemen who emigrated from Norway, Denmark, and Iceland to Northern France during the 8th or 9th century.

A glimpse into the kitchens of early medieval home cooks

The little that archaeologists know about Viking culture comes from small discoveries like the Birka bread. Technically, the term "Viking" exclusively refers to pirates and pillagers of Northern Europe who lived between the 8th to 11th centuries. But contrary to popular belief, most folks who lived in these regions during this period weren't explorers at all, but farmers, fishermen, and craftsmen. While it might seem like a given to imagine a Viking chowing down on a hefty leg of lamb, the medieval Scandinavian diet was primarily foraged. Cattle, sheep, and goats were kept but used more for their dairy than for their meat. More often, the Vikings ate dried fish like herring, cod, and halibut, which could be dried for prolonged preservation and easy transportation — symbiotic with the Norse nomadic lifestyle.

Early medieval kitchens featured indigenous vegetation, including turnips, shallots, beans, peas, barley (which was turned into cereals), dill, parsley, coriander, mustard seeds, wild leeks, garlic, juniper berries, onions, cabbages, blackberries, duck eggs, mead, apple and strawberry wines, and a yogurt called skyr. Some folks even ate seals. Notably, the Birka bread uncovered at the dig sites is strikingly similar to another Norwegian flatbread called lefse, a potato-based offering ostensibly also created by the Vikings.