The History Of Peanut Butter

Peanut butter seems to be a ubiquitous condiment since it's found in nearly 95% of homes in the United States. It has applications far and wide: Besides the standard PB&J, it's used as a filling protein boost in smoothies, a sweetener for breakfast foods like oatmeal and pancakes, and a flavoring for desserts like ice cream and pies. It can also be featured in savory sauces and dressings. So, how did the nut butter become a standard pantry staple?

Many people associate the birth of the spread with the agricultural scientist, inventor, and historical figure George Washington Carver. But, although he was renowned for developing over 300 different applications for peanuts (and, as a result, aptly nicknamed the "peanut man"), the butter variety actually wasn't one of them.

Who really invented the spread? The truth is, we can attribute the creation of this now-loveable household snack to several parties across time. Here's everything you need to know about the history of peanut butter, from its ancient origins to its modern-day use.

The Incas created the earliest known version of peanut butter

Although China is considered the largest producer of peanuts, the legumes are actually native to the Western world, specifically South America. The plant naturally thrives in warm, rainy environments, making the tropical zones of the continent ideal for its proliferation.

Between roughly 1200 and 1533 A.D., South America was home to the Inca Civilization, which occupied an expansive area along the Andes mountain range between modern-day Ecuador and central Chile. Because peanuts were a widely available crop throughout the region, the Incas used the legumes as sacrificial offerings, medicinals, or to prepare marzipan-like cakes, sauces, and fermented drinks. Notably, tribes would roast and grind the ingredient to create a paste. Sound familiar?

Although this derivative isn't quite the same as the peanut butter we enjoy today, it is the first iteration of the spread identified in history. Additionally, it would later serve as the basis for more modern adaptations.

Peanuts emerged in the U.S. 100 years after the Incas

The Spanish invaded South America in the early 1500sbut, by then, the cultivation of peanuts was widespread; other nearby civilizations, such as the ancient Aztecs in modern-day Mexico, were also using the ingredient. The conquistadors quickly discovered the legumes and brought them back to Europe, and it wouldn't be long until traders eventually spread them to other continents like Asia and Africa.

Much later, in the 1700s, peanuts were finally introduced to the U.S. through the transatlantic slave trade. However, it wasn't until the 1800s that the legumes were developed into a commercial crop. Even then, the ingredient didn't become popular until after the Civil War; before this historical event, it was mostly reserved for livestock and a lower-class diet.

During the Civil War between 1861 and 1865, peanuts were mostly cultivated in the Southern states due to the warmer, humid conditions. As a result, armies in the region would rely on them as a key source of protein. Union soldiers had a particular liking for the legume, so by the Reconstruction era, it also became a common ingredient in the North. Peanuts' popularity continued to grow in the U.S. in the late 1800s, thanks in part to P.T. Barnum's traveling circus, which advertised them as a roasted snack, and, of course, George Washington Carver for being an advocate for their prevalent use.

Peanut paste was reintroduced in the States post-Civil War

A couple of decades after the Civil War, in 1884, Canadian chemist and pharmacist Marcellus Gilmore Edson received a U.S. patent to create a form of a peanut paste, which he called "peanut-candy." Making the product involved roasting and grinding the ingredient between two hot surfaces until it reached a butter-like consistency. The heat made all the difference; without it, Edson suggested that you would only be left with flour. He then proposed that sugar (of various amounts) could be added to the result, making it a useful new component to create confectioneries.

The chemist's concoction was still far from modern peanut butter, but adding a heating element to the milling process and mixing in a sweetener took it one step closer to the version we're used to today. For now, the product remained a well-kept secret — until John Harvey Kellogg commercialized it.

Kellogg created the first peanut butter prototype

Physician and nutritionist John Harvey Kellogg is known as the face behind today's breakfast cereal giant. However, Kellogg is also credited for developing the earliest version of modern peanut butter. In 1895, not too long after Marcellus Gilmore Edson's key contribution to peanut butter's history, he was able to patent an updated process to create the spread we recognize today from raw peanuts.

However, rather than slathering it on bread to enjoy as a meal, Kellogg had other ideas for the new food compound. He originally developed the product for his patients at the Battle Creek Sanitarium who were unable to chew solid food. Peanut butter was easy to digest and produce, so it quickly became an accessible form of protein. Kellogg even went so far as to claim that the spread was a healthier alternative to meat, and well-known historical figures like Thomas Edison, Amelia Earhart, and Sojourner Truth were frequent enough visitors of his institution to help promote this to the rest of the country.

The Industrial Revolution led to the mass production of the spread

The Industrial Revolution was already in full swing when John Harvey Kellogg developed peanut butter — historians believe the era began around 1760 and continued through the 1840s. So, it's no surprise that shortly after, several inventions aided in the production and later popularity of the spread, both commercially and at home.

Around 1896, well-known publications like Good Housekeeping advertised the creation of peanut butter with a meat grinder at home (and notably recommended pairing it with bread to eat). However, this process required considerable effort and didn't always guarantee a smooth and creamy product.

With this in mind, inventors started getting more creative. Joseph Lambert, an employee at Kellogg's sanitarium, invented a machine that made roasting and grinding peanuts easier. Due to the success of the appliance, he eventually left the institution to start his own business, called Lambert Food Company, selling the invention. Before long, Lambert had to produce larger versions of the mill to keep up with renewed demand for creating nut butter. In 1903, Dr. Ambrose Straub filed a patent for a formal peanut butter-making machine, and, by then, the U.S. was manufacturing nearly two million pounds of the spread per year.

The first peanut butter company launched in the late 1800s

With multiple options for nut butter creation now widely available, the U.S. saw the first businesses of its kind emerging. The American Refining Company, later renamed the "Krema Products Company," is the oldest peanut butter brand among the bunch and was originally launched in 1898 in Columbus, Ohio — and still lives on today.

Its early claim to fame was its all-natural spread: it had no added salt, sugar, or other preservatives that would be found in later iterations, making it a fairly simple, healthy option. In fact, the only ingredient in the product was the peanuts (we're sure John Harvey Kellogg was proud).

Later, the brand was purchased by Richard Sonksen in 1988, who also happened to acquire Crazy Richard's Peanut Butter. Today, the company's products are sold under the Crazy Richard name, and while its modern spread now has added sugar, nutritionists still consider it one of the healthiest brands of peanut butter you can buy.

The World's Fair spread the popularity of peanut butter

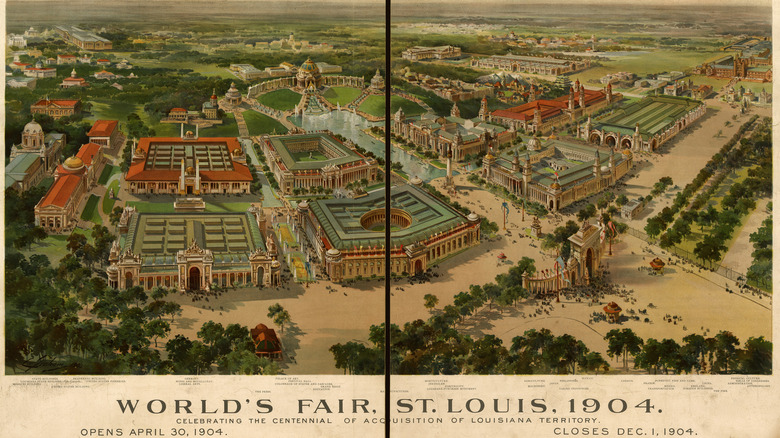

Although a good percentage of the American population was now regularly consuming peanut butter, many people still didn't know about it. However, that all changed when the spreadable snack was featured in the historical St. Louis 1904 World's Fair. At the time, the international event was held every few years, usually alternating host countries. It would highlight a range of industrial and scientific advancements and cultural items from around the globe. Visitors would travel from other nations to see the exhibits, enjoy unique attractions, and try new cuisines.

The exhibition in 1904 was not the first to be held in the U.S. Still, it was notably timely, as the country was at the pinnacle of culinary innovation. As a result, many of the American food staples we see today were established here, including hot dogs, hamburgers, iced tea, cotton candy, and of course, peanut butter. Missouri farmer C.H. Sumner held the only stand featuring the spread at the fair and made a little over $700, valued at roughly $23,860 today. While this may not seem like a lot considering nearly 20 million guests were attending the event, Sumner made quite an impact: Afterward, peanut butter production skyrocketed from 2 to 34 million pounds per year.

Peanut butter became a key source of protein during wartime

Thanks to Kellogg's marketing — and the spread's feature at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis — the U.S. population quickly turned to peanut butter as a healthy source of protein, even in times of tumult. During World War I, between 1914 and 1918, the product was used as a plant-based meat alternative due to rationing needs. And people were getting creative with the substitutions: Peanut butter was the highlight of dishes ranging from soup to "meatloaf" (yes, you read that right).

In 1928, Frank Bench's Chillicothe Baking Company was the first in the history of bread to start selling pre-sliced loaves (created using a production process invented by Otto Rohwedder) to the public, and it was a game-changer. This meant that now, households could spread peanut butter on warm toast without taking the time to cut their own servings. It also led to even more creative combinations like the peanut butter and mayonnaise sandwich popularized during the Great Depression.

By the start of World War II in 1939, PB&J sandwiches were a normal meal for active soldiers and remained a common lunchtime staple even after the war was over. In short, despite the spread being around for several decades, the American population treated it like the greatest thing since, well, sliced bread.

Hydrogenation allowed peanut butter to stand the test of time

Although the spread was seen as highly nutritious and a welcome solution for rationing during wartime, there was just one problem: Peanut butter could go bad. Grocers were instructed to open up the packaged product and stir it frequently; otherwise, the oils would separate, which would lead to spoilage.

Luckily, in the early 1920s, entrepreneur Joseph Rosefield found a solution: partial hydrogenation (PHO). This chemical process involved introducing hydrogen to the naturally occurring oil in the manufactured peanut butter. As a result, the spread remained solid at room temperature, eliminating separation and making it more shelf stable. It was a practice already used in other foodstuffs like margarine, but Rosefield was the first to apply it to nut butter. By 1942, PHO peanut butter had sold more than the natural variety.

In contrast, today's pantry staple no longer goes through the PHO process; the Food and Drug Administration has since discouraged the practice among food manufacturers due to the significant level of trans fatty acids it creates as a byproduct. Instead, producers typically opt to use palm oil or fully hydrogenated fat, which, unlike PHO, do not contain any levels of trans fats and offer the same benefits.

Crunchy peanut butter entered the scene later in the game

Before Joseph Lambert's creation, households struggled to achieve the same smooth texture of peanut butter as John Harvey Kellogg and his team and therefore deemed the homemade version less desirable. Little did they know, however, that nearly 100 years later, people would come to love this consistency — so much so that we still have crunchy (dare we say extra crunchy?) versus creamy debates to this day. So what changed?

When Joesph Rosefield originally filed his patent for the partial hydrogenation process in the spread, he wasn't quite done. Soon after, he licensed it to what would eventually be known as the peanut butter giant Peter Pan in 1928. However, after the brand hinted it would cut Rosefield's funding in 1932, he decided to strike out on his own, notably launching his own company, Skippy.

Rosefield's company featured a research lab, where he developed a new way to produce the spread: churning. This innovation resulted in pieces of peanuts finding their way into the final product, which led to the first mass production of chunky peanut butter. And the people loved it; not only did the crushed nuts add a welcoming texture, but the remainder of the spread was still smooth and creamy — not gritty and coarse like the version that used to come out of a meat grinder. Before long, Skippy outsold Peter Pan in the 1940s and remained America's favorite peanut butter for the following 40 years, according to The New Yorker.

The federal government began questioning what defined peanut butter

Not long Skippy's rise to fame, Procter & Gamble purchased Big Top peanut butter and rebranded it under the name Jif. The company aimed to top Skippy and Peter Pan, so now it was tasked with developing a spread that would sell. And they found it: The brand combined the traditional nut butter with sugar and molasses and used a different oil for partial hydrogenation – a recipe other competitors would soon try to mimic due to its success.

While the general population found this new iteration from manufacturers delicious, the FDA wasn't the biggest fan. With the addition of these sweeteners, was peanut butter really even peanut butter anymore? As a result, in the 1970s, the federal entity eventually set the standard for how the spread is defined even today: For the product to be considered "peanut butter," the FDA says it must contain at least 90% peanuts.

Natural peanut butter came back into full swing in recent years

Of course, with time, more Americans have become — and still are — more health-conscious, realizing the impact of additives in various foods, including peanut butter. That said, there's an increasing demand for more organic alternatives, and according to the National Peanut Board, natural spreads generally have more protein and less saturated fat, sodium, and sugars.

They're also reminiscent of the products the nation saw before Joseph Rosefield introduced the partial hydrogenation process; they're made with peanuts as the main – and sometimes sole – ingredient. However, as you'd imagine, this leads to questions about how a more organic spread can maintain its shelf life. Luckily, we have more modern means to keep food items good for as long as possible. When it comes to natural nut butter, the best way to extend its expiration date is to store peanut butter in the refrigerator or a cool, dry area like the pantry and mix it before consumption.

What does modern peanut butter look like?

A jar of peanut butter today doesn't look drastically different compared to the earliest version of the spread. Its manufacturing process may have changed over the years, but the end product is more or less the same; it's still made with the base ingredients of peanuts, even though manufacturers have since introduced oil, salt, and sweeteners to their recipes for taste and to extend shelf life.

There are also various types of nut butter that are more widely available now. While early innovators like John Harvey Kellogg had already been experimenting with making spreads from alternatives like almonds, they didn't have nearly the same popularity as peanuts, and for good reason: The latter was cheaper to produce and, at the time, had a more pleasing taste, especially before the addition of sugars and other flavorings in later years.

Despite these minor updates, peanut butter has come a long way from the ancient Incas. That said, whether you're team chunky, extra crunchy, or creamy, we can probably all agree that this pantry staple isn't going anywhere anytime soon.