The Explosive 15th Century Roots Of Molecular Gastronomy

A whimsical mixture of chemistry and food art, molecular gastronomy is all about transformations. Simple ingredients like mushrooms, potatoes, and herbs become distilled into foams, gels, and even smoke. At El Bulli, the famed Spanish restaurant that put molecular gastronomy on the map in 2003, even the most benign ingredient could be transformed into something revolutionary. Take its send-up of the humble Spanish olive: what looked like an olive and tasted like an olive was, in fact, a spherical liquid. Your eye and palate may be initially deceived, but your sense of texture exposes the true nature of the dish.

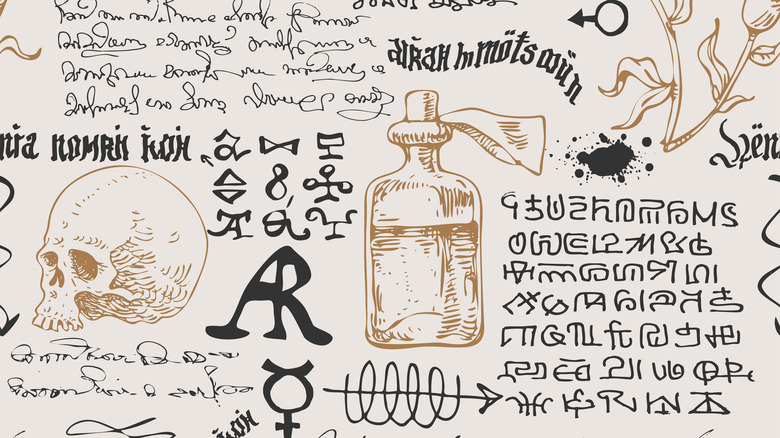

But long before chef Ferran Adrià began turning white beans into foam at El Bulli, chefs of the 1400s were mixing the disciplines of chemistry and cooking, treating their kitchens like laboratories. True, the term "molecular gastronomy" was coined as early as 1988 by Nicholas Kurti and Herve This, the forefathers of this specific field. Yet traces of the subject can be found in 15th-century manuscripts, where recipes took on the role of alchemical formulas. So what exactly is the link between a 15th-century chef's tinkering and a modern-day gastronomist's experiments?

Alchemy and medicine: a tale of two sciences

The culinary practices of old had a connection to two scientific disciplines: medicine and alchemy. Medieval medicine was based on our understanding of the body's four "humors," blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Doctors were in a constant battle to balance these finicky humors, and naturally, the patient's diet became a means to help even out said humors. Hence, some cooks began mixing medicinal science into their dishes, ensuring their cooking would favor their lord's health.

Then there was the once-celebrated science of alchemy, a study on how to transform matter. Not to be confused with witchcraft, alchemy was a respected science in medieval times, more akin to our current respect for chemistry. According to Britannica, many alchemical students were devoted to learning how to transform ordinary metal into gold, but the alchemical discipline was focused on all forms of "transmutation," including transforming the sick into the healthy and the old into the young.

Naturally, this shares some basic DNA with the goal of molecular gastronomy, which seeks to transform food's physical state and appearance in a whimsical way. Alchemy had more links to the kitchen than that, though. Its chemical formulas were referred to as recipes, and its texts often contained authentic culinary recipes. Take an alchemical text found in Italy — within, you can find both a recipe for wine and how to make a dying horse look fat and beautiful (via Science History Institute). So when did all this combine for an explosive collaboration?

How to make your dead chicken sing

While there were alchemists interested in cooking and doctors recommending certain foods for health, the cooks of the early 15th century looked to combine all of this into their dishes. "The Vivendier," a French cookbook with an anonymous author, has the ideal example of the melding of the minds. While it's most celebrated for its liberal use of butter, the book contains a questionable chicken recipe that is probably fatal to eat and definitely explosive.

Devoted to helping the cook "make that chicken sing when it is dead and roasted," the chicken cavity was stuffed with two very unusual ingredients: ground sulfur and quicksilver (mercury). Tied together tightly and roasted, the chicken was expected to produce a high pitch scream with the gases escaping. The recipe further advises that the same recipe will work for goslings and piglets, and if none of the animals didn't scream loud enough, the chef hadn't tied them tightly enough, per Gode Cookery.

Of course, mercury is poisonous, and sulfur is combustible, so this recipe should never be made in any kitchen. But these were two ingredients commonly used by alchemists in their experiments to show how the two disciplines of science and cooking could be combined in a whimsical, albeit dangerous, way. Molecular gastronomy has come a long way from its questionable alchemical origins, but it's nice to know that the art of transforming food has endured through the ages.