9 Types Of Trappist Cheese, Explained

Trappist cheeses have been around since medieval times, and, luckily for cheese lovers like us, many of them are still made using the traditional recipes that were first used in the 12th century. Made exclusively by monks (and occasionally, nuns who got in on the action), abbey cheeses were a delicious way to make enough profit to keep the monastery running while also providing the brothers with piles of seriously tasty fromage.

Originally, these cheeses came primarily from Belgium, Switzerland, and France. Now the recipes are made less in monasteries, with factory-made cheeses becoming much more common (via Le Trappiste Brugge). Many of the monastery cheeses have been given the protected designation of origin, meaning that, like Champagne or San Marzano tomatoes, that particular item can only be made in the original area of production. That also means they can be harder to get because of their smaller production abilities.

These abbey cheeses (also known as monk cheese) are all produced similarly — made with either raw or pasteurized cow's milk (or the occasional sheep's milk); the edible rind is washed throughout the maturation process (via Cheese.com). The washing and brining distinguish these particular varieties from the others; rind-washed cheeses have a noticeably orange-red covering that gives the foodstuff a rather pungent aroma. Yep, the rind is the real reason these stinky cheeses smell the way they do. Cut into one, though, and you'll find a buttery and creamy interior with a gentler taste than you might expect.

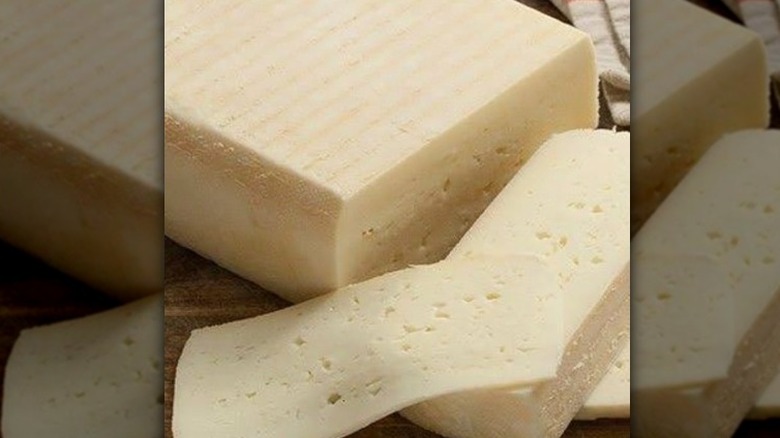

Saint-Paulin

Saint-Paulin is a good start if you're not crazy about cheeses typically described as stinky or pungent. A softer version of some of the other cheeses on this list, this French cheese originated in the Bretagne region but is produced in other places, most notably in Quebec, Canada. Cheese.com describes it as firm yet creamy with a milky aroma and nutty, unctuous taste. The rind on this particular type is edible but is drier than other Trappist cheeses, so it may be sliced off and discarded if you prefer. We suggest soft-bodied wine, like Beaujolais, cabernet franc, or even a Reisling, would be a delightful match, making it a truly approachable option for your next wine and cheese snack pairing.

Monsieur Gustav, a Canadian producer of Saint-Paulin, has this interesting tidbit about semi-soft cheese to help the next time you're trying to choose a texture — "a semi-soft cheese is generally softer than a firm cheese but tastier than a soft cheese." Creamy, buttery, and with a decent amount of flavor sounds ideal for our needs. They also posit that a decent cup of coffee is one of the best things to pair with their monk cheese, making it a perfectly acceptable breakfast or dessert option. See? It is possible to eat cheese all day long.

Port Salut

Much like Saint-Paulin, Port Salut (or Port-du-Salut) is a milder variety of Trappist cheese from France. Originating in the Loire Valley, it has only been around since the early 19th century (via Port-Salut). Because of its late origins, it's one of the first French cheeses to be made with pasteurized milk which contributes to its saleability, according to Cheese Hub. (Raw milk cheeses are notoriously hard to get approved for sale in many countries.) We're also willing to bet that this is the most universally recognized Trappist cheese on this list. Port Salut cheese may or may not have an edible rind, depending on its providence. Factory-made varieties are often wrapped in cloth or wax for easy distribution and must be removed before eating.

The lovely orange rind, not-overpowering aroma, and semi-firm interior ensure that it is one of those grocery store cheeses that make a perfect cheese board. Its approachability makes it great for someone who might be put off by something with a super stinky rind; think of Port Salut as the ultimate washed rind starter cheese. The slightly acidic interior isn't as sweet as some of the Danish abbey cheeses, which tend to have a slightly fruity taste. Instead, this is a more savory option that begs to be melted over fresh farm veggies or sprinkled onto a green salad. It pairs exceptionally well with light and fruity white wines or a dry gin martini.

Chaumes

A Trappist cheese made by traditional methods in France, Chaumes (pronounced "shown") has a gorgeous creaminess with a little hint of grit that gives it a terrifically satisfying mouthfeel. The buttery and elastic texture significantly improves with time, like a lot of washed rind cheeses, so if you can give it a week or so, you might be surprised at the difference it makes. Children will actually enjoy this variety, so your cheese plate can finally be enjoyed by all ages. Often used as a table cheese (but seriously, we think every cheese qualifies as a table cheese, darling!), you can easily turn this little beauty into a show-stopping grilled sandwich. It's known for its superb meltability, after all.

Probably in the middle of the spectrum for rind-whiffiness, Chaumes is good if you're looking for something with a little more aroma and flavor but aren't ready to fully commit to some of the stinkier abbey-produced varieties. It appears runnier than it actually is (as per Marky's) and retains its shape well due to the denseness of the supple, almost bouncy interior. It makes a terrific snacking cheese, easily served with decent crackers and a slice of pear. Add a glass of crisp white wine if you want to posh things up a bit.

Esrom

This type of Danish cheese can be a little harder to find, but if you're lucky enough to have a thorough cheesemonger nearby, you might be able to get your hands on a wheel. Esrom can only be made in Denmark because of its protected designation of origin status, making it a tough find though it is possible. You can also ask for Danish Port Salut if that helps your search for a mouthful of what is "said to be one of the top stinky cheeses in the world" (via Cheese.com). As we've discussed previously, that divine odor mostly comes from the washing of the rind and the subsequent development of specific bacterial cultures. The semi-soft interior has a lovely buttery texture with small holes and a delicate fruitiness — per Cheese Professor — that takes on more flavor with spicier notes when aged.

Named after the abbey (near the village of the same name) where it was first made, Esrom cheese was first made in the 12th century by Cisterian monks (via Cheesemaking). The recipe was lost for a few centuries but was rediscovered in the 1930s and has steadily grown in popularity since then. Scandinavian Specialties writes that the pungent aroma and slightly spicy flavor pair well with dark beers and red wines, sliced into a hearty sandwich or casserole.

Maroilles

Another French offering, Maroilles is known as the cheese of the North. Having been made in the Hauts-de-France region for centuries, with some texts indicating as early as 760 (per Le Guide du Fromage), this cheese has a pedigree for sure. The aroma of the rind can be described as having hits of cellar, damp brick, and undergrowth. The interior, however, is as creamy as you would expect, with mild hazelnut flavors, brininess, and just enough oiliness to make the texture stand out from other monk cheeses (via French Cheese Corner). Pair it with cured salmon and a lively Rhone Valley red wine for an immersive French treat.

Once you've brought home a lovely piece of Maroilles, you'll need to know how to store fresh cheese. Washed rinds cheeses are good for seven to 14 days once opened, so planning is essential — how much cheese will you be able to eat in two weeks? The exposure to oxygen that happens when you remove any waxy coating or wrapping will not only dry out your cheese, but that silky interior is now more likely to absorb other flavors from your fridge. Cheese expert Liz Thorpe recommends wrapping your Maroilles in either specialty "cheese paper" or layering parchment under plastic wrap and securing well. Plastic wrap alone is a recipe for disaster, killing the rind before you get to enjoy it.

Oka

In 1893, a French monk arrived at a monastery in Oka, Quebec, with a recipe for Port-du-Salut (the predecessor for Port Salut and many other washed-rind kinds of cheese) and a plan. The monk, Brother Alphonse Juin, was a master-cheese maker and tinkered with the original recipe until he finally developed what is now known as Oka, one of the best-loved Canadian cheeses today (via Cheese Lovers). The cheesemaking operation was bought from the monks in the early 1980s and continues to be factory-made beside the original monastery. Some connoisseurs (like Le Trappiste Brugge) may insist that factory-made versions pale in comparison to those from an abbey, but there are so many types on the market now that you'll be able to find one that appeals to you.

Perhaps the best indicator of the creaminess of the cheese is the tagline itself — printed proudly on the packaging, it simply reads, "An Irresistible Taste of Melted Butter." If that's not a reason to dig in, we can't imagine what would be. While the company has expanded the line to include several other varieties, Oka Original remains closest to the mild yet slightly bitter cheese first made at the abbey. The orange rind is a little thicker than some other types, so it's up to you if you peel it before adding it to your seasonal cheese plate with pickled peppers.

Père Joseph

This abbey-made cheese comes from South-West Flanders in Belgium. Made according to traditional recipes; it has a complex taste with fruity notes and a soft, creamy texture. It's suggested that this Père Joseph does very well on a cheese board with wine or Belgian beer. Trappist cheeses are typically considered excellent breakfast cheeses, and Père Joseph is a marvelous example of this, served with hearty bread and a smear of jam. The slightly fruity finish also makes it a lovely pairing with dessert if that's more your thing.

The traditionally washed rind is coated in brown wax to slow the aging process, making it slightly different from other Trappist-style products (via Peacock Cheese). Like the familiar red wax-coated Gouda, Père Joseph requires a gentle peeling before consuming, but otherwise, it's a standard abbey-made cheese. The strong aroma gives way to the customary silky texture, and, like other varieties, it has a lingering finish that's both a little salty and sharp. With 52% butterfat content (per The Belgian Shop), the zesty aroma belies the utter creaminess of the satiny interior that melts well but is also perfect for just slathering straight onto a cracker. The odor is often compared to that of Limberger, a notoriously stinky German cheese, so many suggest that it's best for those who prefer something a little more assertive in the nose.

Pont L'Eveque

From the northwestern region of France known as Normandy, Pont L'Evèque was originally made by Cistercian monks in the 12th century in the abbeys surrounding the bridge that the cheese is named after. Producer Isigny Ste. Mare still makes their pale ivory cheese in rectangular wooden molds, just as they were centuries ago, turning and washing the rind by hand until maturity. Normandy's dairy farmers have long asserted that their products are some of the best in the world, as reported by Elle et Vire, and the origin-protected Pont L'Evèque seems to live up to the hype. Those dairy farmers might be onto something, too. After all, Normandy's most famous cheese, camembert, is nothing to turn your nose up at. Served on a cheese board with a chunk of camembert, a handful of dried figs, and a chilled cider sounds like heaven to us. If you're looking to bring out even more of the aromas and flavors, try a rich red wine.

Pont L'Evèque's aroma is as pungent as you would expect. Still, it's interesting to note that many aficionados claim that the scent retains a whiff of Normandy's rolling hills and fresh hay (via The Gourmet Cheese of the Month Club). While that might sound like a bit of a stretch, it's hard to know for sure unless you've been to the Norman countryside to get a snootful.

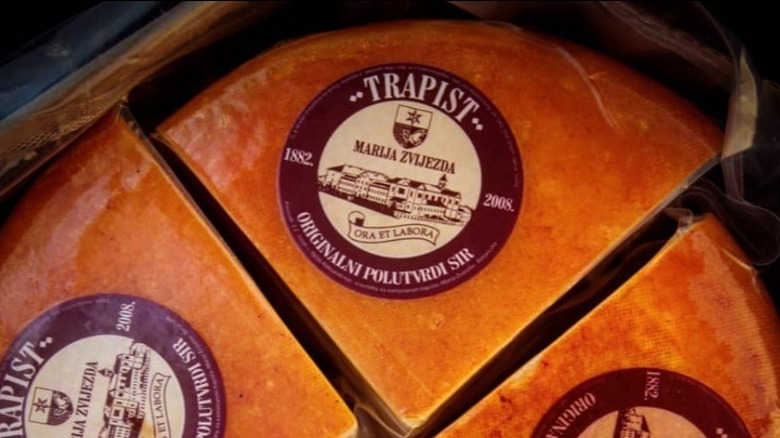

Marija Zvijezda

Our final entry comes from Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, complete with a long and winding story about more than a delectable cheese. However, the cheese chapter alone is fascinating enough for our purposes. The BBC writes of the largest Trappist monastery in the world, now home to only three monks, and the lost-recipe cheese named for the monastery. Marija Zvijezda (Mariastern abbey), later called Trappist of Mary Star, had been produced by the abbey until 1996, when the monk who knew the word-of-mouth recipe passed away. That's right — this production method was so heavily guarded that only one monk at a time was allowed to know the entire recipe, with other monks only specializing in one particular aspect to keep it hidden even from them.

Luckily, with a little ingenuity and help from some French Trappist monks adept at making washed-rind cheeses, the recipe was resuscitated in 2007 (as per Anadolu Agency), much to the relief of everyone involved. Currently, two of the three monks living in the abbey are in charge of producing this mildly scented (relatively speaking, at least), supple, and creamy cheese with a touch of saline and sweetness. The smooth rind is meant to be eaten, so nothing slows you down when you cut into one of these gorgeous rounds.