Kumis: The Alcoholic Horse Milk Likely Linked To Genghis Khan

Yes, you read that right. From South American Yerba Mate to English high tea, to a cuppa joe at your favorite local coffee shop, beverages play a significant role in many different cultures. They're sustenance. They're a social instrument. They ... taste nice, too. Introducing: Kumis.

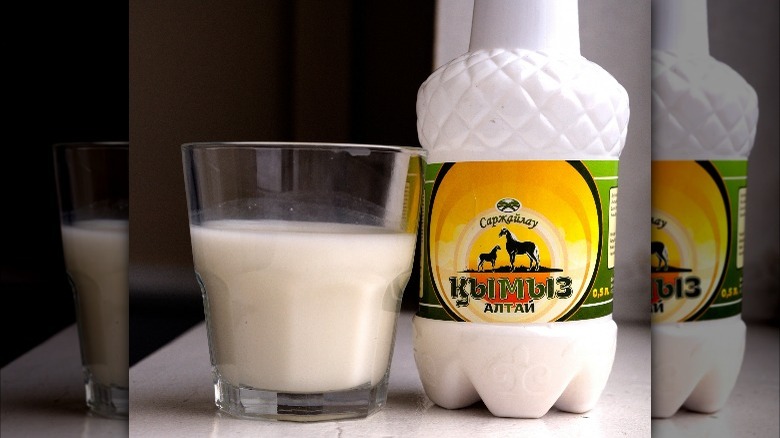

Kumis was the Central-Asian alcoholic bevvy sipped by "infants and Genghis Khan," per Atlas Obscura. It is roughly only 2% ABV. Kumis (aka "airagh") is white, foamy, fermented horse milk with a taste that's been described as "champagne mixed with sour cream." The Botai people were drinking it more than 5,000 years ago. In what is now Kazakhstan, they tamed wild horses and fermented their milk – its naturally high sugar content makes the fermentation process as easy as churning and waiting for alcohol to form, per CalorieBee. The alcohol content comes from lactic acid fermentation. But was the drink really linked to Genghis Khan?

It's been tough for historians to know for certain because, by definition, nomadic cultures tend not to leave much behind once they pick up and relocate – historical records included. But, Harvard assistant professor of anthropology Christina Warinner has been able to identify some of the dietary habits of the historically-elusive Mongolians by analyzing their dental plaque. "Dairying," says Warinner, started cropping up in Central-Asian peoples' dental records as early as 3,000 B.C.E., but milk drinking didn't reach its height until 1200 B.C.E. – the same time that "mobile pastoralism" really started taking off.

Choosy warriors choose kumis

The timeline checks out. Per Britannica, Genghis Khan was born in Mongolia around 1162, roughly when and where the Botai were fermenting kumis. The warrior-ruler would go on to dominate all the villages in Mongolia, founding the Mongol nation with famously-gnarly executions of every enemy along the way. And his entire campaign was fueled by kumis. (Probably.) Often, says Atlas Obscura.

Drinking horse milk (and its opportune timing in history) might have facilitated the nomadic lifestyles of people like the Mongols. As described by Harvard Magazine, Warinner believes horses' endurance over long distances "enhanc[ed] herding capacity, access to pasturage, and the control of larger territories." For Genghis K., larger territories were the name of the game: At its peak, his empire spanned Eastern Europe all the way to the Pacific Ocean – across Hungary, Korea, Siberia, and Tibet. Plus, horses could dig beneath snow to access grass and feed themselves, enabling winter travel, per Mongolian Ways. Mongol warriors were known to be accompanied by three to five horses each.

Milk even played a big role in Mongolian religious practices. According to historian William Stephens, milk was sprinkled into the air as an offering to spirits and ancestors, or as a prayer for protection and good fortune. It's even sprinkled over caskets at funerals (via Missiology: An International Review). In the 13th-century text "The Secret History of the Mongols," when his wife was kidnapped by enemy troops, Genghis Khan performs a milk offering for her safe return.

Kumis today

In 1911, author Elizabeth Kimball Kendall wrote of her travels in Mongolia, "To appreciate the Mongol you must see him on horseback – and indeed you rarely see him otherwise, for he does not put foot to the ground if he can help it. The Mongol without his pony is only half a Mongol, but with his pony, he is as good as two men," (via Mongolian Ways). Today, Mongolia is home to over 5 million horses – nearly twice the number of humans, who can grab bottled kumis from street vendors. The beverage can also be found in Russian grocery stores. In Russia, the milk is typically drunk a half hour before eating a meal as a health-packed aperitif, says CalorieBee.

Believe it or not, kumis is said to promote gut health, boost metabolism, strengthen the immune system, and keep the cardiovascular and nervous systems running smoothly, according to the North American Journal of Medical Sciences. Perhaps that's why Russian playwright Anton Chekhov allegedly turned to kumis as a tuberculosis remedy, although it reportedly failed to cure him, per "Food and Dairy Microbiology." Even Leo Tolstoy (Russian author of classics "War and Peace" and "Anna Karenina") referenced escaping from life's problems by drinking kumis in his 1882 book, "Confession." So, if you're thirsty to experience Mongolian culture and history for yourself or channel your inner Genghis Khan, kumis might be a way to do that.