New Study Finds Link Between SNAP Requirements And Mental Health

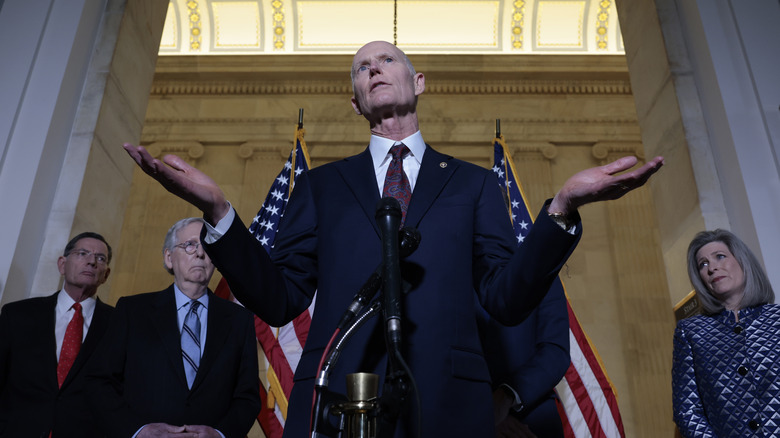

On June 29, Florida senator Rick Scott proposed that the country should reintroduce work requirements for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), according to WFLA. Many of these requirements were temporarily suspended by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which was signed when the first major wave of the pandemic broke upon the United States in March of 2020.

"For our country to thrive, we can't let their toxic plan of increased handouts and getting something for nothing continue," Scott argued in a piece published by the Wall Street Journal.

If the proposed Let's Get to Work Act of 2022 passes, WFLA reports, work requirements will once more apply to adults on SNAP, expanding to include adults ages 50 to 59 and parents of children older than six. It will also override many of the "no-good-cause" exemptions that allow states to circumvent the requirements. Whether the measure goes anywhere will have to be seen. However, recent research has found the severe mental health impact that such requirements have.

Work requirements raise anxiety and depression

One month after Rick Scott unveiled his plans to restrict access to SNAP, Northwestern University published a study into the mental health effects of limiting access to SNAP with work requirements.

The study focused on West Virginia, which instituted requirements in nine counties as a pilot program. They saw a 26% increase in mental health visits related to depression among women enrolled in both SNAP and Medicaid and a 12% increase in visits related to anxiety. Men also reported similar issues, but not at such a sudden increase. Researchers suspect the difference may come down to women typically bearing the responsibility of feeding families.

Moreover, researchers found that these requirements don't improve employment numbers. They only reduce the number of people receiving benefits. "So essentially, these work requirements harm people with no measurable benefit to the economy," Lindsey Allen, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, concluded.