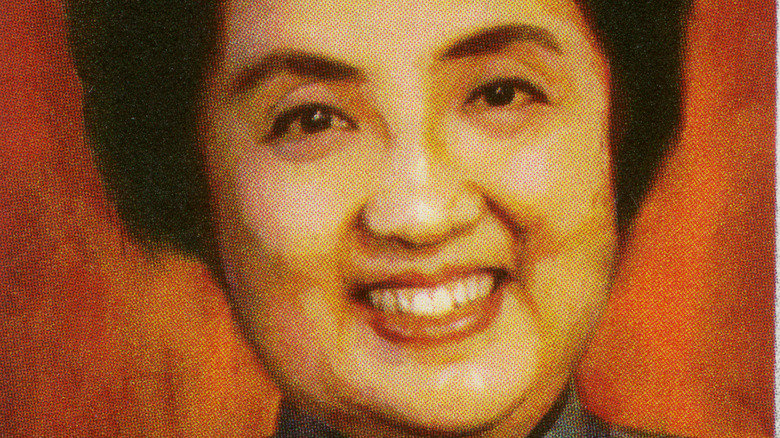

Joyce Chen's Important Impact On American Cooking

Joyce Chen may not be a household name like her contemporary, Julia Child, but her impact on American cooking might be just as important. Where Child brought French cuisine into the homes of everyday Americans, Chen brought an approachable form of Chinese cooking (via Food52). Her numerous influences on Chinese-American restaurants, and American kitchens include the invention of the flat-bottomed wok, numbered menu items, and the buffet-style dining where Americans were introduced to the many Chinese dishes for the first time (Joyce Chen Foods).

Chen was born in what was then known as Peking (now Beijing), China in 1917, and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts with her husband, who worked as a fine art importer (via Food52). After becoming a housewife and mother, Chen found herself cooking more often for her family. After a batch of her Americanized egg rolls sold like hot cakes at a school event, she felt there was potential to do more with her food. She would go on to open four eponymous restaurants in the Cambridge area, release the "The Joyce Chen Cook Book," and make friends with Child, who was already a fan of Chinese cuisine. This connection would help her obtain her own cooking show called "Joyce Chen Cooks" on WGBH, the same network as Child, where it would run for one season between 1966 and 1967. She would continue cooking in her own restaurants, and even launched a line of sauces.

Chen passed away in 1994.

Joyce Chen's legacy

Food52 noted Chen's ability to adapt Chinese foods for the American palate. Chen understood that the average American at the time could only stomach so much novelty in terms of recipes, and also terminology. To help Americans who may have been intimidated by the idea of Chinese pot-stickers, she coined the phrase Peking Ravioli during an episode of her show. Those egg rolls that inspired her culinary journey were also made with an inauthentic recipe that included half a pound of a "good hamburger" mixed with sherry, sugar, pepper, cornstarch, and brown gravy with syrup. In her own cookbook, she recommends the use of ingredients more commonly found in U.S. markets, and leaner cuts of meat that would have been in vogue at the time (via Serious Eats).

Chen's approach may come across as pandering to some (via Food52). Today, cooks at all levels sprinkle the word "authentic" onto menus and restaurant reviews more liberally than any seasoning in their kitchen. Chen knew her audience though, and that she was introducing them to new ideas. Thanks to her approach and work, those ideas are now a more common part of the American culinary landscape.