James Beard, America's First Foodie

"In the beginning, there was Beard." —Julia Child.

So begins James Beard: America's First Foodie, a new documentary from director and producer Beth Federici and coproducer Kathleen Squires, which airs Friday, May 19, on PBS. Though food lovers know Beard's name well—chefs and diners flock to the James Beard House for dinners, and the James Beard Awards have been dubbed the Oscars of the food world—few are familiar with the man himself, and specifically his invaluable contributions to the American food system as we know it.

RELATED James Beard Awards Names Outstanding Restaurant and More "

Think the farm-to-table movement is only recently a darling of chefs and restaurateurs? Beard was a champion of local food long before most gastronomes were paying attention. While most American chefs were looking to France for inspiration, Beard was celebrating the local berries, chanterelles and seafood he grew up eating on the Oregon coast.

In fact, it was Beard's mother, Mary Elizabeth Jones, who taught him how to eat. Jones, a British immigrant, led her son through markets, teaching him to skillfully discern which vegetables were the freshest or which chickens the plumpest. Instead of playing the role of homemaker, she earned a reputation as a renowned thrower of dinner parties and an excellent cook. The apple doesn't fall far from the tree.

Like his mother, Beard always walked to the beat of his own drum. In an era when it was illegal to be a homosexual, he didn't try to hide the fact that he was gay. Sadly, his brazenness got him expelled from Reed College, but he eventually traveled to Europe, where he indulged his love of the arts and fine food. As a stand-in for husbands who didn't want to accompany their wives to the opera, Beard managed to attend the theater almost every night. When he returned to the U.S., he even made a go of it as an actor, performing in theaters in New York, Portland and Seattle, and scoring a small role in Cecil B. DeMille's 1927 silent film, The King of Kings.

James Beard and Julia Child | Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

James Beard and Julia Child | Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

When he needed to supplement his income, Beard did what struggling actors still do today: He joined the hospitality industry. He started a catering business in 1937 called Hors d'Oeuvre, Inc., and, as they say, the rest is history. His most famous dish was a simple tea sandwich of brioche, raw onions, chives and his mother's mayonnaise recipe.

Three years later, he penned Hors d'Oeuvre & Canapés at a time when it was practically unheard of for a man to write a cookbook. In the documentary, Ruth Reichl says, "Cookbooks in those days were the domain of women. . . . I think it would have been very strange for a man to write a cookbook." Beard went on to write more than 20 books over the course of his career. In 1946, he also hosted the first food television show, aptly named I Love to Eat. Though the show broke new ground, it brought him little notoriety. Decades later, however, he was a frequent TV guest alongside his pal, Julia Child.

Off the small screen, Beard was unrivaled in his impact as a food columnist, cookbook author, culinary instructor and restaurant consultant. When he wrote about a restaurant, people took notice.

Take Chez Panisse, for instance. It was Beard's review of the Berkeley restaurant that put Alice Waters on the map and turned her restaurant into a California institution.

When The Four Seasons restaurant first opened in New York City in 1959, it was Beard's vision: He was the one who conceived of a menu that changed with the seasons (hence the restaurant's name). The kitchen worked directly with farmers and producers who grew food specifically for the restaurant, and the menu highlighted which farms the ingredients were sourced from. It was a novel concept at a time when most dinner tables in America were dominated by meat loaf and potatoes.

For all of his influence as a writer and teacher, it is perhaps his humanitarian work that has made the greatest impact. Beard, a consummate entertainer who derived his greatest pleasure from feeding friends, was saddened to learn how difficult it was for housebound seniors to access a proper meal. So, along with New York Times food critic Gael Greene—a former cooking student of his—he cofounded Citymeals on Wheels. The pair raised $35,000 in 1981 to launch the program, which, 36 years later, raises $19 million a year.

Today, cooking at the James Beard House is a rite of passage for any young chef. It is an opportunity to connect with community, showcase regional cuisine and, above all, honor the tremendous legacy of Beard himself—an innovator and pioneer of locally grown and thoughtfully prepared American food.

This month, we're going Under the Hood and into the art and science of the culinary world to find the emerging designers, independent farmers and (spoiler) major corporations creating trends from the ground up.

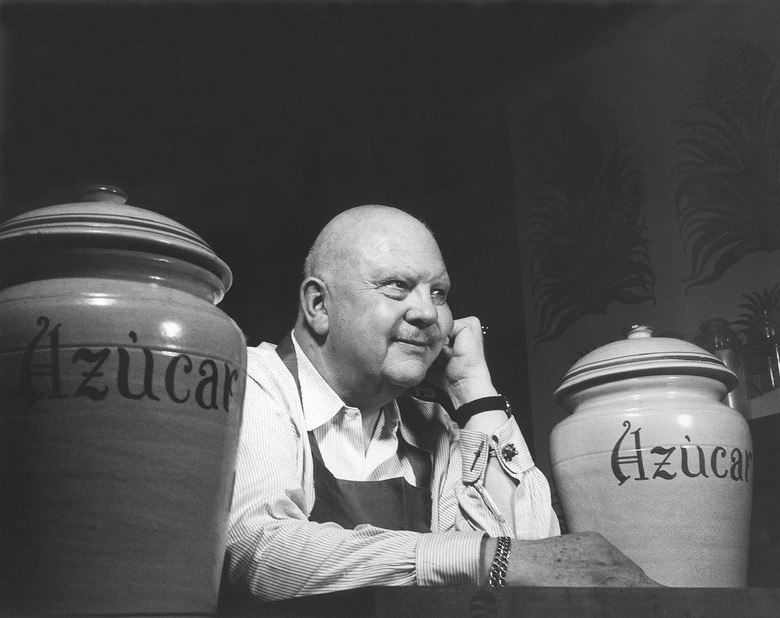

James Beard was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1903 and frequently returned to the coast over the summer, where he celebrated the seasonal ingredients he grew up with.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

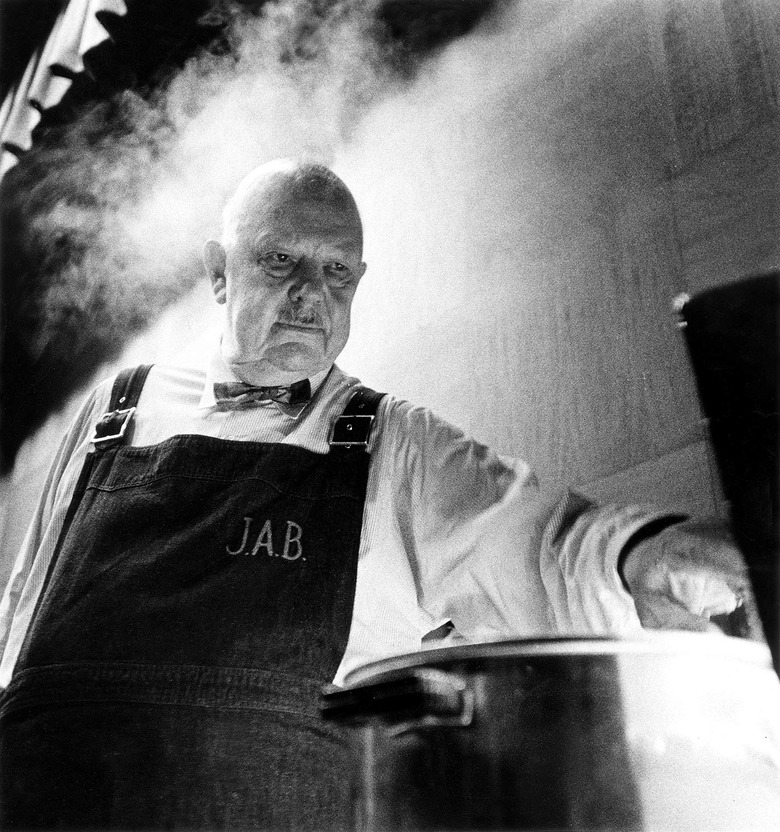

He was expelled from Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Although the college blamed the expulsion on bad grades, the explanation held by Beard himself is that it was because Beard was gay.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

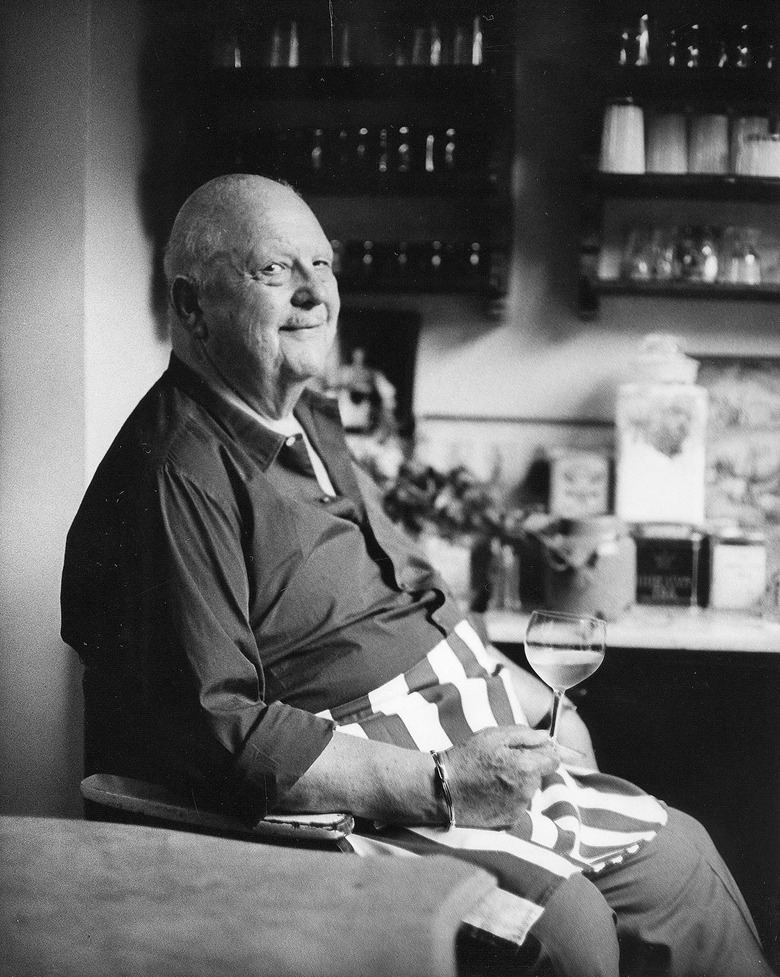

He tried to be an actor and appeared in a few plays and a silent film, but eventually started a catering business to pay the bills.

Photo by Ken Steinhoff, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

He was pals with Julia Child and frequently appeared on TV alongside her.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

Together with former New York Times restaurant critic Gael Greene, he founded Citymeals on Wheels.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

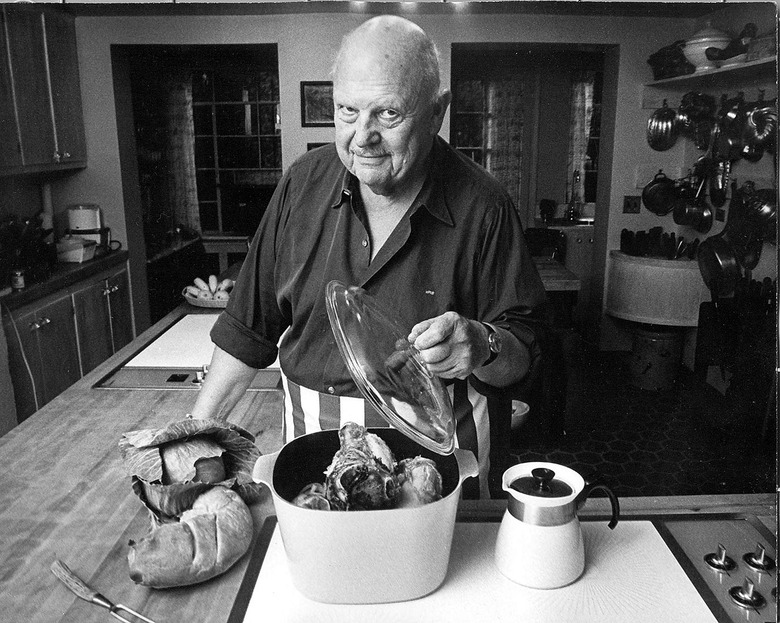

He wrote more than 20 cookbooks, including a book on cooking outdoors and one on French cuisine.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

His 1974 review of Alice Waters's Chez Panisse put the restaurant on the map.

Photo by Dan Wynn, courtesy of the James Beard Foundation

In 1946, he hosted the first-ever food program on TV.

Photo courtesy of the James Beard Foundation