Why David Chang Loves To Incorporate Koji Into Cooking

If umami is your thing, you can't afford to not know about koji. At Harvard University's 2013 Science & Cooking public lecture series, via Eater, Chef David Chang described koji as "when rotten goes right," and he has spent much of his illustrious Momofuku career harnessing its power to achieve predictable, consistent culinary results. In case you've never heard of it before, koji (Aspergillus oryzae) is a type of fungus used in fermentation. It starts as mold spores and is the secret behind such powerful umami ingredients as mirin, rice vinegar, and soy sauce.

As Chang tells Fine Dining Lovers, koji is "responsible for the fragrance and the floral notes in sake and the pungency of miso," but on its own, it tastes a lot like Fruity Pebbles cereal. At the Harvard lecture, the chef shared that much of his research into koji was motivated by a desire to produce a top-global-quality food product in America since many of the "luxury" products U.S. foodies import from other countries like Parmigiano Reggiano and white truffle oil are the bottom of the crop. "The rest of the world sends us their worst," says Chang. But American-made koji could change the global playing field.

Koji brings big flavor from small particles

The three key factors necessary for koji fermentation are yeast, bacterial activity, and room temperature. The spores are typically infused with soybeans, barley, or rice, and the mold consumes the grain base in order to fuel its natural reactions. It's a similar process to how kombucha SCOBY or sourdough starters create other fermented foods. But, that's about where the similarities end.

Think of koji like a yeast starter, launching the bread-making process into gear. Koji does the same thing for fermentation. Its amylase and glutamate enzymes ferment grains while simultaneously curing meats and converting starches into sugars. The result is a highly complex flavor profile: Umami-forward, yet salty-sweet and funky. Koji can also be mixed with salt and water and used as a pickling marinade called "shio koji." (Gastronomic microbiology never tasted so good).

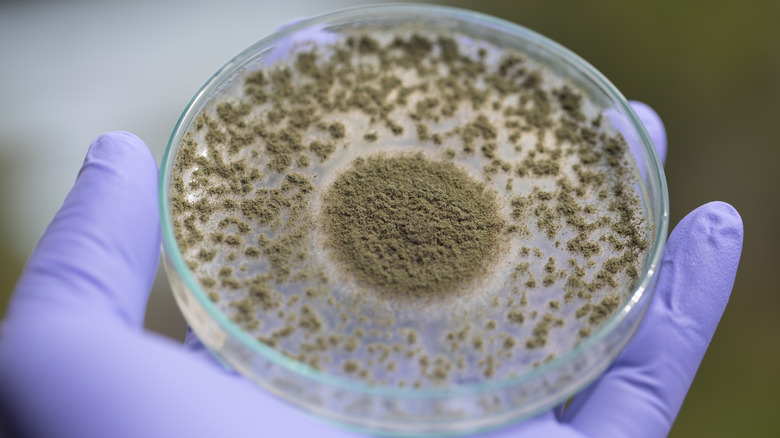

Made properly, koji looks like a layer of snow and emits a sweet aroma. Dangerous mold smells like green bananas. For this reason, koji's popularity has been a little slow to start in the U.S. due to strict food safety regulations, which don't exactly make room for food produced by bacteria. But you can still try out koji for yourself.

Ways to get funky with koji

Koji-fan David Chang has created a line of fermented condiments in collaboration with Kaizen Trading Company and Momofuku Culinary Lab to help introduce koji to unfamiliar home cooks. "Hozon" is a salted, koji-fermented condiment similar to miso paste but without soybeans. "Bonji" is a soy sauce substitute made from lentils, nuts, or chickpeas. These condiments can make for an easy intro course to koji's unique taste, and get your brainstorm rolling for other ways to use it in the kitchen.

Vegan triple Michelin-starred fine dining giant Eleven Madison Park swears by koji. As Brock Middleton, fermentation sous chef, tells Grub Street, "When you're not using animal protein, it's even more important to find inventive ways to unlock umami." The Eleven Madison Park kitchen is cranking out koji carrot tartare, miso-mole, and more.

Cooking with koji isn't just for the pros. Jeremy Umanski of Larder Deli in Cleveland, Ohio co-authored a book with koji expert Rich Shih called "Koji Alchemy: Rediscovering the Magic of Mold-Based Fermentation," which includes recipes for such inventive creations as Popcorn Koji, Korean Makgeolli, Roasted Entire Squash Miso, and Amazake Rye Bread.

Koji can rapidly age cheeses and dry-age meats. Due to its reaction with starches, it also adds a savory umami kick to bread and pastries. Use it for a crunchy pickle on daikon, sunchokes, eggplant, or beets. Traditional Japanese koji rice is only the beginning.