13 Most Influential Food Critics In History

Everybody's a critic! Especially when it comes to food. But only a select few have the privilege of reaching the masses with their opinions and insights about the culinary scene. A food critic can make or break a restaurant's reputation with a few lines of perfectly prepared prose. Armed with palates and pens, these arbiters of taste digest the whole experience of a meal, from presentation and taste to history and social context, to serve up reviews that can transform the way that diners experience the sacred act of eating a meal.

The history of food criticism as an art has its roots in 18th-century France, where food was not only a way of life but a status symbol. Critics like Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière were known to frequent the finest dining establishments in the French capital, reviewing meals that consisted of fifteen courses. In recent times, however, there has been an effort to democratize the art of the restaurant review. Critics like Jonathan Gold focussed their efforts on small, under-the-radar eateries tucked away in immigrant neighborhoods.

Though we now live in an era where people choose a restaurant based on Yelp's most popular picks, which are based on the reviews of the masses, a few select individuals have ushered us into this era. So next time you're savoring a special meal, don't forget to pause and think about the eaters who came before you responsible for honing the craft of thinking about food.

Antonin Carême

The original French foodie Antonin Carême was a celebrity chef before the term even existed. Born in the late 18th century into poverty, Carême started out as a kitchen boy in a chophouse when he was eight years old, and at age 15, started working at a pâtisserie in one of the most fashionable neighborhoods in Paris. Just a few years later, he was turning heads with his very own bakery, which became famous for baked goods made into the shapes of famous buildings.

His creations caught the eye of a French diplomat, and after that, voilà, Carême went on to serve the upper echelons of Parisian society, including Napoleon himself. It's hard to overstate just how influential his contributions were to the world of gastronomy: He penned one of the first modern step-by-step cookbooks, popularized the double-breasted white coat and tall hat as a chef's uniform, and invented the four "mother sauces," including béchamel, which became the backbone of French cuisine. If you're a fan of French cuisine, chances are you're familiar with Carême's work whether you know it or not.

Robert Sietsema

Nobody knows the New York food scene like Robert Sietsema. Not your average high-brow food critic, what sets Sietsema apart is his knowledge and appreciation for the lesser-known and harder-to-find restaurants often overlooked by bigger food critics. For a time, he even had a column that highlighted New York's best sandwich of the week. After earning a degree in English and moving to New York to join a punk band, Sietsema got his start as a critic at the Village Voice, and he's now been writing about the New York food scene for three decades.

Sietsema has a lot to say about the current state of the dining scene. In an interview with BOMB magazine, he likened the experience of eating at a fast-casual restaurant to squatting "down like a medieval peasant eating with your fingers in the field." Observations like these make it clear that he is criticizing a lot more than just flavor; he demonstrates an understanding of the cultural and historical context of the restaurants that form his subject matter. And while many restaurant critics call beforehand, Sietsema prefers to go anonymously and pay in cash so that he gets the "real" dining experience.

Nina and Tim Zagat

If you're a regular on the restaurant scene, then you're probably familiar with the Zagat rating. Decades before Yelp or Google reviews, the Zagat guide first arrived on the food scene in 1979 with the aim of democratizing the restaurant review process. Often framed near the entrance of restaurants, the rating is based on a 30-point scale and separated into three categories: food, décor, cost, and service. This was the brainchild of Nina and Tim Zagat, two New York lawyers (and foodies) who revolutionized the process of restaurant reviews. After the couple moved to Paris, Nina's interest in food culture led her to take classes at Le Cordon Bleu, where she learned about the technical aspects of cooking. When the couple moved back to New York, they had the idea of aggregating a massive number of reviews from diners and subjecting them to statistical methods to come up with a method of reviewing restaurants that relied on "everyday" diners rather than famous food critics.

The signature thin, burgundy Zagat guide has since sold millions of copies and has become an industry standard for proof of a quality dining establishment. Although these days we regularly rely on aggregated reviews for just about all goods and services, Tim and Nina Zagat pioneered the idea of user-generated content with respect to restaurants. Next time you go out to eat, look for the Zagat review.

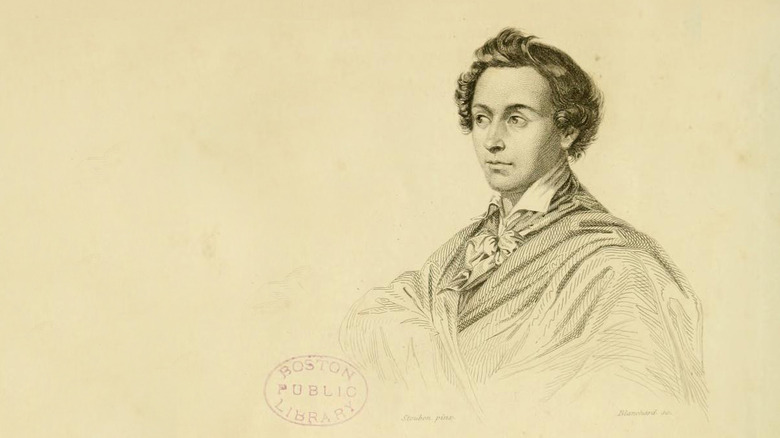

Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière

It's not hard to make enemies as a restaurant critic, of which Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière, a French aristocrat and a pioneering food critic, had many. Born in 1758 to wealthy parents, La Reynière began as a theater critic and eventually turned his sights onto the world of gastronomy, which was evolving rapidly in the wake of the French revolution at the end of the 18th century.

In 1803, he had the idea of creating an almanac for food lovers, which compiled reviews of dishes and restaurants in his signature witty, scathing style. The idea proved so popular that over the next nine years, he published eight volumes of his "L'Almanach des gourmands," and it became well-known among the Parisian bourgeoisie. Although food guides are common in today's gastronomic landscape, La Reynière's idea was extremely novel at the time and ended up ruining the careers of many fledgling chefs and restauranteurs. In fact, he had so many enemies because of his harsh reviews that he was forced to leave Paris altogether in 1812, and he faked his own death just to see how few friends would attend his funeral. And there were few indeed.

Mimi Sheraton

A true New Yorker through and through, Mimi Sheraton was dubbed "the Queen of Cuisine" by the Greenwich Village Historic Preservation Society. After all, not everyone can claim to be the first female food critic at The New York Times. The daughter of a fruit merchant father and a mother who was a "very good and ambitious cook," Sheraton grew up in Brooklyn, where the multitude of immigrants exposed her to a wide variety of cuisines from around the world. She was poised to use her well-trained tastebuds for the benefit of all New Yorkers.

After attending New York University and working as a copywriter and then a magazine editor, she began to pursue food writing as a hobby. And New Yorkers were lucky that her hobby turned into a career because, by 1975, she was writing reviews for The Village Voice and The New York Times, where she was eventually hired as a food writer. As a journalist, she covered restaurants from Manhattan's posh Upper East Side to red sauce Italian joints in Coney Island. Sheraton even went on to win multiple James Beard awards for food journalism, including one for her book "The Whole World Loves Chicken Soup" and another for an article on the fortieth anniversary of the Four Seasons.

Ruth Reichl

A pioneer of the farm-to-table movement, Ruth Reichl has a special place in culinary history. Reichl started writing about food in the early 1970s and went on to publish several food-centered memoirs that have been translated into 18 languages. She was also co-owner of The Swallow Restaurant from 1974 to 1977 in Berkeley, California, which helped transform the value of the culinary landscape to put more emphasis on sustainable, locally sourced ingredients.

Her fusion of the culinary and literary gained her a job at the Los Angeles Times, where she managed the food section, which was the biggest in the country at the time. Her exceptionally frank memoirs deal not only with the subjects of food and eating but of motherhood and feminism. She was eventually handed the helm of Gourmet Magazine, where she served as the famous publication's final editor before it closed in 2009. Reichl is active on Twitter, where she writes almost poetically about the foods she loves. She also came out with a cookbook in 2015, "My Kitchen Year: 136 Recipes That Saved My Life," that explores her life after Gourmet Magazine through the lens of cooking.

Henri Gault

Becoming a tastemaker in Paris is no easy task. Henri Gault, the co-founder of the famous Gault-Millau annual guide to restaurants, along with his partner Christian Millau, changed the way that French cuisine was perceived with his emphasis on culinary modernity. As France was nearing the end of the "Trente Glorieuses," the thirty years of economic prosperity after World War II, the focus of the food scene in the French capital began to shift from traditional cuisine that took hours of preparation and catered to a stuffy, wealthy clientele to lighter, smaller menus with shorter cooking times that could be enjoyed by more people. And thus, Nouvelle Cuisine was born.

After Gault and Millau coined the term, they sought to highlight the new cuisine in their annual guide, which helped to popularize it and give it a platform for international recognition. The influence of many of the principles of nouvelle cuisine, like an emphasis on local ingredients and simple preparation methods, can be seen today in New American cuisine. So next time you're enjoying a simple, perfectly prepared plate at a modern restaurant, you might have Henri Gault to thank.

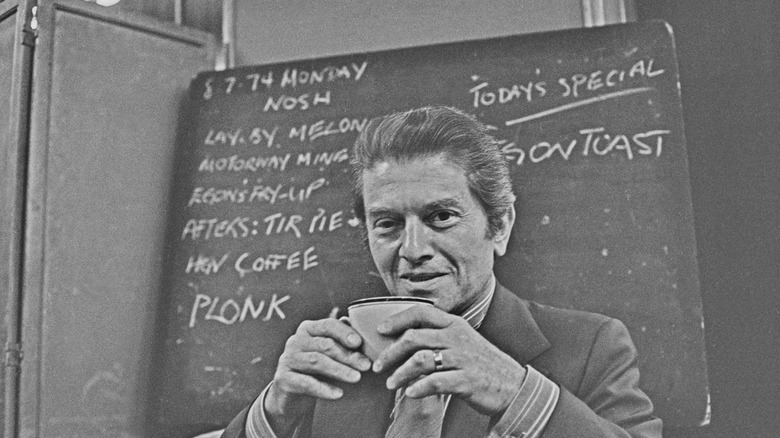

Egon Ronay

As it turns out, Britain's "king of good food," as he was lovingly dubbed by The Guardian, was not from Britain at all. The late Egon Ronay came to the United Kingdom shortly after the Soviet occupation of Hungary during World War II, where he managed a restaurant in Picadilly Circus. Irritated by the lack of quality food available to the public in Britain, Ronay wrote his first restaurant guide, which was based on the French Michelin guides, in 1957 and it sold over 30,000 copies.

Ronay was dedicated to being a totally impartial judge of food, and he never once accepted anything he was reviewing without paying for it. He had great faith in his adopted country despite British cuisine's bad reputation, once saying that "it won't be long before food in this country [the UK] is better than it is in France." A fan of simplicity, Ronay bemoaned overcomplicated menus and an excessive focus on presentation, and he is widely regarded in Britain as one of the most influential forces on national cuisine in recent times.

Michelin Brothers

The highly coveted Michelin star is perhaps the most famous internationally recognized symbol of restaurant quality. While many food critics that took the culinary world by storm started out working in restaurants or in magazines, the Michelin brothers have a very different origin story. André and Édouard Michelin began their journey to gastronomic super-stardom by starting a company that manufactured tires. But they were forward thinkers.

The Michelin travel guide, the first of which was published in 1900, was meant to encourage the use of automobiles by enticing consumers to travel further to visit the list of restaurants recommended by the guide. As we now know, the idea was a wild success. Michelin now publishes guides that cover the globe and a Michelin star has become synonymous with culinary excellence. In fact, it is rumored that the famously hardened celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay started crying when one of his restaurants lost its 2-star Michelin rating.

Francis Lam

The son of Chinese immigrants, Francis Lam's career as a gastronomic authority started at the Culinary Institute of America, where he wrote about his experiences in the kitchen. Through a series of unexpected events, he met Ruth Reichl (another famous tastemaker on our list) and began writing freelance stories about food for Gourmet Magazine. Many years and four James Beard Awards later, Lam is the host of "The Splendid Table," a radio show on NPR that discusses culinary culture and best practices in the kitchen.

Lam has long championed the important role that immigration has had on the culinary landscape, which he has written about extensively in a column for The New York Times that discusses the subject in depth. Although his parents were initially disappointed that Lam didn't go after a traditional career in law or medicine, they eventually came around when he turned into one of the most influential American food critics of our time. Now, with one of the best food podcasts out there, thousands of people tune in to hear what Lam has to say about how best to enjoy our favorite activity: eating.

Jonathan Gold

A native Angelino, Jonathan Gold ate his way through Los Angeles with a deep, nuanced appreciation of everything that it took to create a meal worth eating. Unlike the archetype of the stuffy, suit-wearing restaurant critic who needs a tablecloth and a salad fork to savor an entrée, Gold drove around LA in his pickup truck through the city's many immigrant neighborhoods to discover the best that there was to offer. And he found it.

Gold brought hole-in-the-wall eateries and mom-and-pop restaurants that were on the fringes of the LA culinary scene into the limelight. And in doing so, he changed the way that mainstream consumers thought about the role of a food critic. Although he was famously bad at submitting assignments on time to the Los Angeles Times, where he served as a food critic, he more than made up for it with his passion for the craft. In 2018, after Jonathan Gold's devastating death, the world lost one of the brightest, most adventurous food critics out there.

Tejal Rao

It is impossible to fully appreciate cuisine in the United States without paying homage to the immigrant experience. Tejal Rao is from London, the daughter of a mother who was born in Uganda and grew up in Kenya and an Indian father, and she spent time growing up in Kuwait, France, and Sudan, so she had a wide range of dining experiences to draw upon when she began to write about food. With a bachelor's degree in literature and experience as a line cook in California, Rao had exactly what it took to become one of the premier food critics of our time.

Her work encompasses not only nuanced critiques of upscale restaurants, but she also writes recipes and dives into the social aspect of food culture, reporting on everything from the human impact of fine dining to the cooking grandmas of TikTok. Rao currently lives in Los Angeles, where she serves as the first California food critic for The New York Times. Not only does she know how to write about food, but she is an avid cook and gardener, testing out recipes so that she can share her insights with the rest of us.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

While most people who considered themselves foodies in 19th century France were focused on the upper crust of society, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin had a broader appreciation for the whole host of classes and cultures that made the Paris dining scene what it was. Even if you've never heard his name before, you're probably familiar with the phrase "you are what you eat," an inaccurate paraphrasing of a quote from Brillat-Savarin: "Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are."

Though he worked as a lawyer and a judge for most of his professional career, Brillat-Savarin is known best for his book "The Physiology of Taste," which he published in 1825. The work includes meditations, recipes, and reflections on everything having to do with his varied epicurean experiences. The tone of the book ranges from informative to comedic, written with wit, knowledge and a keen sense of humor, and it has become one of the world's seminal texts on food and the culture of eating.