Every Type Of Champagne Explained

It's hard to think of a type of wine more revered than Champagne. Produced in northern France in the region of the same name, the sparkling beverage is simultaneously a symbol of celebration, luxury, and patience. Its winemaking process is not one to be rushed, and the most basic styles require a 15-month aging period (via Comité Champagne).

With such a meticulous approach, it's no surprise that Champagne garners international recognition and is regularly a source of inspiration for sparkling wine producers worldwide. Indeed, many viticultural regions create high-quality bubbles following the same technique used in the alcoholic beverage, also known as the traditional or champénoise method. This entails making a still wine and then having it undergo a secondary fermentation in the bottle to create bubbles. To determine the final flavor and sweetness level, a liqueur de dosage — essentially cane sugar and wine — is added before bottling.

No matter the similarities in method or grape varieties, the Champagne region stands out as a leader in all things bubbly. With so many options — not to mention price points — on the market, it's worth breaking down what distinguishes one bottle of Champagne from the next.

Doux and demi-sec

Believe it or not, Champagne production was originally skewed toward sweeter styles. In the 1800s, Barbe-Nicole, the widow at the helm of Veuve Clicquot's success story, produced highly sweet, bubbly wine with as much as 300 grams of residual sugar per liter (via Smithsonian Magazine). To put it in perspective, popular dessert wines such as sauternes count 120 to 220 grams per liter (via Wine Folly). While sugar levels varied, Champagne was a decidedly sweet beverage for many years.

These styles are no longer at the core of sales, but production has not halted entirely. If you're looking for a sweet fizzy drink or want to pair Champagne with dessert, sugar is the key ingredient. Nowadays, residual sugar levels are a mere fraction of what they have been historically, and the sweetest style — doux — starts at 50 grams per liter, with the next sweetest — demi-sec — containing 32 to 50 grams per liter (via Comité Champagne). You'll probably find it easier to track down a bottle of demi-sec, which should still satisfy your desire for a sweet wine.

The higher levels of sugar make these styles of Champagne fuller-bodied and more flavor-forward. As such, they may not be what you'd reach for to quench your thirst on a hot summer day, offering richness and complexity to match a decadent dessert. Consider serving them with pastries at tea time, to round off a festive brunch, or as an apéritif with cheese.

Dry and extra dry

If you took these terms at face value, it would be natural to assume that dry (also labeled as "sec") and extra dry Champagne describes wines with low sweetness levels. However, the former consists of residual sugar levels between 17 and 32 grams per liter, whereas the latter sits between 12 and 17 grams (via Comité de Champagne). Confusing, indeed. As it turns out, the reference point is a little distorted since it was originally used to label wines that were considered dry back when sweet Champagne was the norm.

If you're in the market for slightly sweeter bubbly wine to serve as an apéritif, with spicy food, or as a light dessert, these styles are a good midpoint between doux or demi-sec and brut. That said, you might find it tricky to track down a bottle, as these sparking beverage types don't represent a large portion of the market. Still, reputable houses such as Champagne Taittinger, Veuve Clicquot, Champagne Pommery, and Champagne Lanson release them every now and then.

Brut and extra brut

Common house Champagne often tends to be produced as brut or extra brut. These classifications reflect a sweetness level of six to 12 grams of sugar per liter for the former and zero to six for the latter (via Decanter). Compared to a still wine, brut Champagne contains more residual sugar, but it's worth noting that the grapes are harvested particularly early to maintain high acidity. Consequently, the taste isn't so much sweet as rounded and softer on the palate. Extra brut styles take it a step further, adding minimal amounts of sugar in the liqueur de dosage to maintain a dry, high-acid sparkling wine.

For an easy-drinking bubbly that pairs well with a range of foods and pleases a large crowd, brut Champagne is your best bet. Whether you're sipping on it as an apéritif or serving it with soft cheese or fried chicken, it offers a gentle balance of acidity and rounded fruit flavors. Meanwhile, extra brut is the way to go if you want to pair Champagne with delicate seafood and oysters or enjoy a crisp, zingy style.

Brut nature and dosage zéro

Champagne zealots often swear by brut nature, aka dosage zéro styles, for the purity of flavor. Per the term "dosage zéro" — or zero dosage — no sugar is added to the wine before bottling, leaving it as high-acid as ever. Brut nature Champagne may still have up to three grams of residual sugar. However, the amount is negligible and naturally occurs from ripeness in the grapes.

That's not to say the wines are unbalanced or sour — merely that they are the epitome of refreshing crispness. As long as the Champagne is properly made with ripe fruit that expresses aromas specific to the vineyard, the result is pleasant and a favorite for an increasing number of people. Still, you need to be on board with tart flavor profiles to enjoy these particularly dry bubbles.

Many people are firmly rooted in the brut nature camp, especially those in the wine industry. Popular among sommeliers and natural wine enthusiasts, zero dosage follows the same philosophy of not adding anything to a wine. As Beverage Journal reports, exports of brut nature were up by more than 30% in recent years.

Vintage

Likely the most touted style, vintage Champagne is the stuff of collectors, wine aficionados, and padded wallets. It refers to wines made with grapes from a specific year (aka "vintage") that showcased superior growing conditions and an exceptional harvest. Considering that the Champagne region is in the far north of France at the extremity of optimal viticultural latitudes, it's worth noting that climatic conditions such as frost can spontaneously wreak havoc on crops.

Some wines require blending various harvests, whereas the best years are highlighted by producing wine solely from that period. Champagne producers make the call to declare a particular vintage, rarely doing so more than three times per decade. As such, these bottles tend to garner high prices and prestige since they only represent about 5% of production, expressing characteristics specific to the vintage in question (via Forbes). Aging requirements are more stringent and require a minimum of three years, which further ups the price and status.

Since vintage Champagne is so reputable, it tends to have qualities that allow it to age for several years. Older wine has a range of features that make it distinct from when it was bottled. Aged Champagne even starts losing its characteristic bubbles. Whether you drink the vintage stuff shortly after bottling or ten years later, it is typically more complex than non-vintage styles, making it an excellent option to sip on solo while savoring the flavors and aromas that stand out from that year.

Non-vintage

Most Champagne produced is non-vintage, consisting of wines blended from various vintages. As sommelier Victoria James explains, you're typically looking at a composition of three to five vintages in a bottle (via VinePair). Since weather conditions can be unpredictable in the north of France, it is risky to place production solely in the hands of one harvest. To guarantee a steady flow of bubbles and some uniformity, non-vintage Champagne is produced by combining assorted base wines before they undergo the secondary fermentation process.

Given this careful craft, non-vintage styles are typically fruity, well-balanced, and easy crowd-pleasers. The wines must be aged for a minimum of 15 months before release, though they often exceed this time. As the primary production of the area, non-vintage Champagne is often created in brut styles, which round out the flavors while maintaining a bright freshness on the palate (via Comité de Champagne). With a more modest price tag and greater volume on the shelves, a non-vintage bubbly is an excellent option for celebrations, day-to-day drinks, and pairing with food.

Blanc de blanc

There's plenty to be said about the sweetness levels and winemaking practices used to produce Champagne, but when it comes to the grape varieties involved, it's pretty simple. Blanc de blanc translates to "white of white" and consists of bubbly made with only white grapes. In theory, this can be chardonnay, pinot blanc, pinot gris, arbane, and petit meslier, but chances are the Champagne will be 100% chardonnay. According to Comité de Champagne, less than 1% of the region's total vineyard area is planted with the latter four varieties. That said, if you come across a bottle that includes those grapes, you'll want to scoop it up and savor its rarity and particularities.

Blanc de blanc tends to be a favored style among Champagne drinkers, thanks to its delicate freshness and bright flavors. Chalky notes are a common feature, attributable to the soils in which most of the chardonnay grapes are grown. Aromas of apple, pear, citrus, and tropical fruits mingle with hints of white flowers, salinity, and minerality. Over time, this style of Champagne takes on the scents of brioche, honey, dried fruit, and spices. Whether as an apéritif or paired with fresh seafood, a blanc de blanc is always a great option to pour.

Blanc de noirs

On the other end of the spectrum, blanc de noir means "white of black." This style of Champagne is just as golden as you'd expect, but it's made with red wine grapes, commonly referred to as "black" due to their deep, dark color. In the pressing stage of winemaking, careful attention is required to ensure that the grape skins have minimal contact with the juice collected to retain a pale hue.

The two grapes used in blanc de noirs are superstar pinot noir and lesser-known pinot meunier. Bottles can be single varietals or showcase a balanced blend of the two grapes. Even though you probably wouldn't be able to identify a blanc de noir by looking at a glass of it, a couple of sips should lead you in the right direction. The red grapes tend to exude more weight and body on the palate, making this a bolder, more structured style of Champagne.

Aromas of stone fruit, red and black berries, citrus, and tropical fruit are often present. Additionally, notes of spice and flowers are commonly detected. Given its heftier body, blanc de noir is a great option to pair with food, including meat and bold cheeses.

House style

Whereas some people love the mystery and surprise of popping open a bottle of vintage Champagne, bubbling with unique flavors and aromas specific to the year, other people prefer consistency. Knowing that a particular brand will deliver the same experience every time is part of the reason people become loyal customers. And once a consumer narrows in on the characteristics they are drawn to, they are more likely to return to this brand if they are in the market for higher-end bottles. That is essentially the basis behind house-style Champagne.

Champagne houses (the business behind popular brands such as Veuve Clicquot) typically purchase grapes from growers and produce and market a line of wines with their label (via Union des Maisons de Champagne). To build a customer base and identity, each brand creates a wine blend that becomes its signature non-vintage style. Since the mix is a combination of wines from various vintages, it is skillfully reproduced year after year. Variations such as the percentage of grape varieties, ripeness, maturation, dosage, and winemaking processes result in distinct styles across Champagne houses.

Rosé

If you think rosé Champagne is a frivolous style only intended for people who want something pink and bubbly in their glass, think again. It is often one of the most prestigious types of Champagne, not to mention among the most expensive due to the multilayered winemaking process. Although a wine connoisseur might scoff at you for speculating that rosé is made by mixing red and white wine, that is, in fact, totally acceptable in Champagne (via Comité Champagne).

In these instances, white wine is produced and blended with 5 to 20% pinot noir (or occasionally pinot meunier) wine. Alternatively, the rosé can be made following a maceration method which entails leaving the skins to mingle with the juices for up to 36 hours. In both cases, the resulting wine is varying shades of salmon, pink, or raspberry. Given the presence of red wine or contact with the grape skins, rosé Champagne is often fuller-bodied with a bolder flavor profile. Still, it is bright, fresh, and fruity, making it an excellent apéritif or pairing with food. Unlike the image it conveys, rosé Champagne tends to be crisp and dry, rarely displaying perceptible sugar.

Prestige cuvée

Arguably the best type available by any Champagne house, the prestige cuvée is made using the first juice pressed from grapes (aka tête de cuvée). Not only is the best grape batch used, but these wines are typically made with fruit from the top vineyard sites in stellar vintages. Additionally, they are aged for a long time before release and tend to have the capacity to age even longer in the cellar. As Gayot reports, the style is always vinified with a brut dosage, maintained low to highlight the features of the fruit.

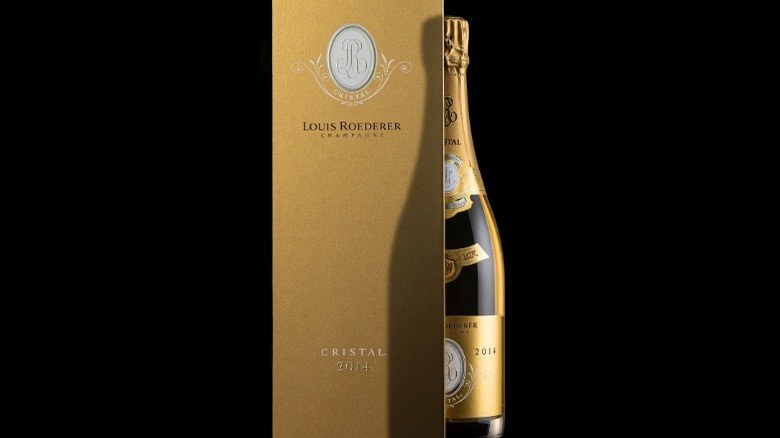

Considering the various levels of excellence, it goes without saying that this Champagne is quite pricey. Yet, this style is a symbol of quality, luxury, and rarity for bubbly wine lovers with extra dollars to spend. Perhaps the most famous prestige cuvée Champagnes are Moët & Chandon's Dom Pérignon and Louis Roederer's Cristal, which have each garnered plenty of praise in their own right. Typically sold in dazzling bottles that often come with their own box, this sparkling wine is as much about image as it is about flavor.

Grower

If you've tasted your way through the major Champagne house styles — or stopped after a few because you weren't satisfied — consider picking up a bottle of grower bubbly next time you're at the wine shop. This classification refers to sparkling wine made by the farmers who grow the grapes. In other cases, growers sell their fruit to Champagne houses or to cooperatives that produce the final sparkling wine product (via Wine Folly).

Grower Champagne typically comes from a small plot of vines tended to and harvested by the growers themselves. Once the fruit is picked, the growers produce Champagne following the same process as larger establishments. That said, yields are much smaller and concentrated in a specific area, making these wines an excellent reflection of the terroir. Bottles are commonly labeled as "RM," which stands for "récoltant manipulant" and translates as "grower producer."

While grower Champagne doesn't denote a quality level, it is certainly more of an artisanal product made on a smaller scale. If those are features you're seeking, and you want to step outside the usual bubbly lineup, it is an excellent category to explore. Keep in mind that marketing budgets will by no means match those of large Champagne houses, so you may need to do some research to track down producers.