The Beginner's Guide To Biodynamic Wine

These days, when you venture to your local wine shop, you might be met with plenty of bottles with unfamiliar labels. We're not talking Austrian reds labeled "blaufränkisch" or mysterious rosés labeled "ramato." Rather, we're talking about terms that describe the way a wine was produced. You may have seen "natural" or "organic" wines, but what does that even mean, anyway?

To many consumers, "biodynamic" is one of those unfamiliar terms. It sounds great if you care about the environment — "bio" is usually a positive, right? And who doesn't want to be dynamic? But if you really want to learn about how different wines are produced, it's a good idea to know exactly what biodynamic wine is and how it's made.

That's why we chatted with Mark Osburn, the lead sommelier at SommSelect, an online wine club that delivers wine (including the biodynamic stuff) to your door. He explained to us the basics of biodynamics and gave us a better understanding of why this type of farming is beneficial for the environment and eco-savvy wine drinkers everywhere. Let's dig into biodynamics for beginners.

Biodynamic farming is considered better for the environment

So, what exactly is biodynamic farming? It's placed in contrast to conventional farming, Mark Osburn told us, which uses a wide array of synthetic, manmade products to grow wine grapes. Most wines are farmed conventionally, so the use of these chemicals and compounds is widespread. But biodynamics, by contrast, focuses on "basically eschewing all sorts of synthetics, these chemicals like fungicides, herbicides, pesticides," Osburn explained.

Biodynamic and organic farming have a lot in common, but according to Osburn, "biodynamic takes it many steps further, and it really focuses on the actual farm itself, like the microcosm. You want to enrich, nourish, and allow your microcosm to thrive, so you're using a lot of local preparations, you're bringing in livestock, you're installing beehives probably, you're planting cover crops to include more diversity, and you really want the soils to speak, you want them to be alive. And that's where it all starts, in the soil. So it's about really making your microcosm thrive with a biodiverse system."

Most agree that farming biodynamically is better for the environment. "When biodynamics is practiced on a small scale, I think it absolutely is better for the environment, ten-fold, compared to conventional farming," Osburn said. We don't yet know what the effect of biodynamic farming would be if we as a society were to practice it on a large scale, but its small-scale use is certainly promising.

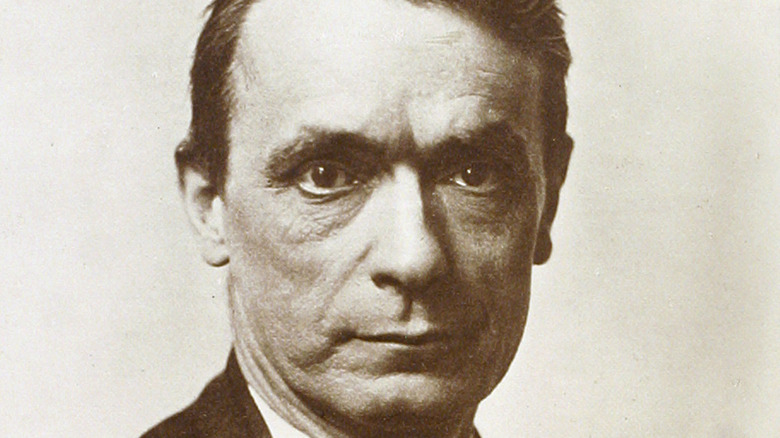

Biodynamic farming was created by Rudolph Steiner in the 1900s

The origins of biodynamic farming can be traced back to around 1924 when philosopher Rudolf Steiner was asked by German farmers to address the first apparent negative impacts of industrialized farming. The farmers were worried about the continued fertility of their soils in the wake of the use of nitrogen fertilizers. This is when Steiner likened the soil to a plant's digestive system, according to Demeter, one of the main certifying bodies for biodynamic farming. Steiner claimed that "a farm comes closest to its own essence when it can be conceived of as a kind of independent individuality, a self-contained entity."

Just seven years later, there were already around a thousand biodynamic farms popping up in regions where farmers were concerned about the effects of the industrialized farming practices that were, at the time, becoming ubiquitous in much of the world. A hundred years later, as we face a growing environmental crisis, more farmers are turning to biodynamics as an alternative to the destructive farming methods introduced at the dawn of the industrial age.

Biodynamics aren't just applicable to winemaking

If you're hearing about biodynamics these days, most of the time it's in reference to winemaking. However, Mark Osburn told us that this farming method isn't only applicable to winemaking — it's a general farming practice. "Back when Steiner created this a hundred years ago, I don't even think wine was on his mind," he said.

But in the world of wine, the word "biodynamic" has gained a reputation as an eco-friendly term that can effectively help sell wines to environmentally concerned consumers. "It's not a new practice, but you mostly see it in wine because it's a buzzword that's really taken off," Osburn explained. "Especially in the 21st century, you've got all these consumers that are eco- and health-conscious. You want to be putting clean things in your body, and that's why it's caught fire with the wine industry."

We all want to be more conscious consumers, and many who have the luxury to spend money on wine want to make sure their dollars are going to producers doing their part to reduce their negative impact on the environment (and, you know, not pumping their wines full of additives in the process).

Not all biodynamic wines are labelled biodynamic

But here's where things get tricky, because labels can have a big impact on how we feel about what we buy. It's great to say you want to try biodynamic wines, but how do you know which ones are actually biodynamic and which aren't? While you can generally trust a label if it says a wine is biodynamic, that doesn't mean that all biodynamic wines are labeled as such, Mark Osburn told us. That's because it can be prohibitively expensive for many smaller producers to apply for biodynamic certification.

When asked if there were any biodynamic producers that don't label their bottles, Osburn said, "there are many, many, countless farmers who ... are only farming a few hectares. They meet all of the rigorous demands certified biodynamic does, even certified organic, but they just don't have the time or the money to consistently slap that logo on the back of their bottles. It sucks because we are a very visual people, and we're susceptible to buzzwords, and seeing 'certified organic' is, of course going to spark someone's interest, even if they don't know what it is."

Additionally, many producers would like to farm biodynamically, but it can be time-consuming and expensive to actually get to that point. The certification itself is pricey, of course, but there's also the fact that biodynamic farming generally requires more labor, according to Osburn. That's why it pays to research the producers you're buying from if you really care about the effects of biodynamic farming. "It's the smaller guys who are doing this just because they want a better ecosystem and cleaner wines," Osburn said.

There are two main biodynamic certifying bodies

So, how exactly does a farm get biodynamic certified? According to Osburn, it can be an intense process. There are essentially two main certifying bodies for biodynamic agriculture – Demeter, which certifies a wide range of farms (not just vineyards for winemaking), and Biodyvin, which specifically focuses on wine. Farms must be certified organic before they undertake the process of transitioning to biodynamic farming. Osburn said that it can take about a year to go from being an organic farm to getting that biodynamic certification.

However, for farms that are not yet organic certified, the process can take significantly longer. Osburn told us that it might take some farms three, four, or even five years to get that biodynamic certification. This highlights why actually obtaining that certification may not be right for some producers. Those who have very small operations or very specific customer bases might find that applying for certification doesn't make sense from a business standpoint, even though they may be using biodynamic principles to farm their grapes.

Biodynamic and natural have different meanings in winemaking

For many wine consumers, it can be tricky to navigate different terms used on wine bottle labeling. There are clear distinctions between organic and natural labeling, and we've already covered that organic" and biodynamic are similar with some differences. But what about "natural" wine? Are all biodynamic wines natural?

Not necessarily, Osburn said. Actually, it's the other way around. "Almost all natural wines that I know of come from biodynamically or organically farmed grapes," he noted. But a good chunk of "natural" winemaking takes place in the cellar, not just on the farm.

Per Osburn, "natural wine, loosely (because I don't think there's a defined, technical definition), [means that] in the cellar, you're intervening as little as possible. You're trying to make the wine as natural as possible. It's about eschewing additives in the winery ... like tannins, acid, Mega Purple, sugars, sulfur, that kind of stuff. If you're doing none of that and allowing the wine to ferment naturally and age it without interfering a lot, and bottling it with just a little sulfur or maybe no sulfur, that qualifies for natural wine."

So, while many natural wines are indeed biodynamic, the two terms don't have the same meaning.

It's easier for some wine regions to farm biodynamically than others

While it would be easy to say that all winemakers and grape growers should transition to biodynamic farming as soon as possible, it's not necessarily easy in some parts of the world. The fact is that it's easier for some wine regions to farm biodynamically than others. Osburn told us that winemakers in warmer wine regions generally have an easier time with biodynamic farming. "Warm, sunny, drier climates can farm biodynamically much, much, much easier because, really, the big issues when it comes to biodynamic farming is mildew and grape rot," he said.

In a cool, rainy climate, grape growers are likely to struggle with the growth of mold and mildew, which can ruin their crops. To stay financially viable, these growers have to resort to fungicides — otherwise, there's a good chance that their crop won't survive. Admittedly, there are some cooler regions that do manage to farm biodynamically, though there are generally other factors that essentially negate the risk of rot development. Alsace, an exciting winemaking region on France's border with Germany, boasts many biodynamic farms despite its cool climate, but this is largely because the Vosges mountain range traps bad weather, rendering the region relatively dry.

When it comes to wine regions in the United States, most winemakers on California's central coast would likely have an easier time farming biodynamically than those in New York's North Fork.

There are some spiritual elements to biodynamic wine production

One factor that separates organic and biodynamic farming is an element of spirituality that biodynamic farming boasts that organic farming does not. Not all biodynamic farmers buy into this breed of spiritual thinking, but many do. According to Osburn, biodynamic farming is "like organics but someone who has spent a lifetime practicing Eastern medicine. It's not founded and rooted and backed in deep, hard science; it's a holistic approach. It's about spirituality, it's about the cosmic forces ... but you don't have to do that."

Perhaps the most well-known and among the most provocative of these supposedly "spiritual" practices is filling a cow horn with manure and burying it in the vineyard, which is meant to "enrich the soils and let them retain more carbon," per Osburn. These cow horns are buried in the vineyard in the fall, and come spring, they are retrieved from the ground, and the manure mixture is combined with water to create a kind of "tea" that's used in the vineyard, per Biodynamic Trainee.

The process might sound odd, but many winemakers have seen success using the method.

Many biodynamic producers adhere to the biodynamic calendar

Another oft-written-about aspect of biodynamic farming is following the biodynamic calendar. This calendar is based on moon phases and the zodiac, according to the U.K.'s Biodynamic Association, and it can help wine growers know when to complete what tasks in the vineyard and beyond. There are four different types of days according to the biodynamic calendar: root, leaf, flower, and fruit. Different tasks are undertaken on different calendar days. For example, according to Beckmen Vineyards, on leaf days, winemakers should avoid spraying or harvesting. Fruit day is preferred for harvesting grapes.

These practices can also extend to the cellar, but not every winemaker will abide by these guidelines once the grapes have actually been picked. "In the cellar, it's a lot more loose," Osburn told us. "Yes, you have to try and be as minimal in intervening as possible, but they don't have set rules for a lot of things."

The biodynamic calendar might tell you when wine will taste best

The biodynamic calendar isn't just useful for winemakers, though. Some believe it can even inform consumers on when they should drink that nice bottle they have stashed away. According to Natural Merchants, many advise against drinking wine on root days — this is when wine is believed to have more of a subtle, earthy flavor, so it's apparently harder to pick up on the pleasant fruity qualities. Leaf days are also regarded as less than ideal for drinking wine.

Those who put stock in the biodynamic calendar will tell you that fruit days are the best times to drink wine because it's said to result in fruitier and more vibrant flavors. Flower days are also an acceptable time to drink wine, especially if you're sipping a more aromatic variety — whites like Riesling may be at their prime during these days.

Of course, not every winemaker who practices biodynamic farming necessarily abides by this calendar, and you're not likely to regret opening that special bottle on your birthday if it does happen to be a root day. However, it can be interesting to taste the wine on different days to see if you can notice a difference.

There is some evidence that biodynamic wine tastes better

So, we know that biodynamic wine tends to be better for the environment, but how much does it matter when it comes to taste? First of all, you're not likely to be able to tell if a wine is biodynamic or not just by taking a sip of it. While some natural wines have a distinctively gamey flavor profile that's easy to spot, the same cannot be said of wines that come from grapes that have been biodynamically farmed. However, there is some evidence that biodynamic wines could taste better than their conventionally farmed counterparts.

Studies conducted by researchers from UCLA found that biodynamic wines scored on average 11.8% higher than other wines that were not farmed with biodynamic or organic methods. These trends have been discovered in both France and in California. And this appears to be true even when the wines are unlabeled.

In this case, it doesn't look like biodynamic farming reduces the quality of wines produced. In fact, it looks like the opposite is true. Whether this research will continue to bear out in the marketplace remains to be seen.

It pays to research producers and think more critically about winemaking

So, what's the moral of the story when it comes to biodynamic wine? If you want to purchase a product that has a minimally negative impact on the environment, it may be worth it to pay a few extra bucks for the biodynamic stuff. But just keep in mind that not all biodynamic wines are labeled. If you really want to dig into the sustainability of the bottle you're holding, your best bet is to do some research on the producer. This can give you a better idea of what you're getting and how it's impacted the environment. You might just learn a little more about wine in the process.

And while thinking critically about the wine you're buying is a great place to practice more conscious consumerism, we shouldn't stop with the vine. All of our agricultural products have an impact on the environment, and thinking more critically about where all of our food comes from is essential to building a healthier, more environmentally friendly future for all of us. It just so happens that wine is an exceptionally enjoyable place to start.