Was Duncan Hines A Real Person?

We might know Duncan Hines the way we know Betty Crocker, Chef Boyardee, Sara Lee, Oscar Mayer, and Uncle Ben — per Chicago Tribune. But like a few of these brand names, Hines the brand was a real person who was once known for his travel and dining guides, not just the bakery quick mixes that bear his name today.

Per Food & Wine, the real Duncan Hines was born in Kentucky in 1880. His father was a former Confederate soldier who had been injured during the Civil War and was unable to care for his children. Because Duncan's mother had died when he was just four, his father's injuries meant Duncan, along with another brother, were sent to live with their maternal grandparents. Hines credits that move with the realization that food could be much more than just sustenance. "Not until after I came to live with Grandma Duncan did I realize just how wonderful cookery could be," he said. His soft spot for Southern cooking was also nurtured by his grandmother, who served him the classics — from candied yams and cornbread to country ham and "turnip greens with fatback."

Duncan Hines was a salesman who kept notes about places he liked

As much as he loved food, Duncan Hines was no cook. Per NPR, being a traveling salesman selling office stationery exposed him to meals of inconsistent quality, so he began carrying a notebook to write down the addresses of all the places whose cooking he enjoyed. Among his scribbles: "The kitchen is the first spot I inspect in an eating place. More people will die from hit or miss eating than from hit and run driving." It is said he made note of everything, from the cleanest diners to the most sumptuous offerings, be it a good cut of beef, or a delectable bun. NPR says Hines also "appreciated regional cuisine, quickly discovering in which part of the country to brake for broiled lobster tail (New England) and where to stop for fried chicken (Kentucky)."

His biographer, Louis Hatchett, says "His restaurant notes were extraordinarily accurate. As word spread among his family and friends, people were begging him to share the list he had created. There was nothing out there like it," he says. "In 1935, sick of being pestered, he finally sent out a little blue pamphlet in his Christmas cards, containing a list of 167 restaurants across 33 states that he could safely recommend."

The Hines name lived on although the memory of the man didn't

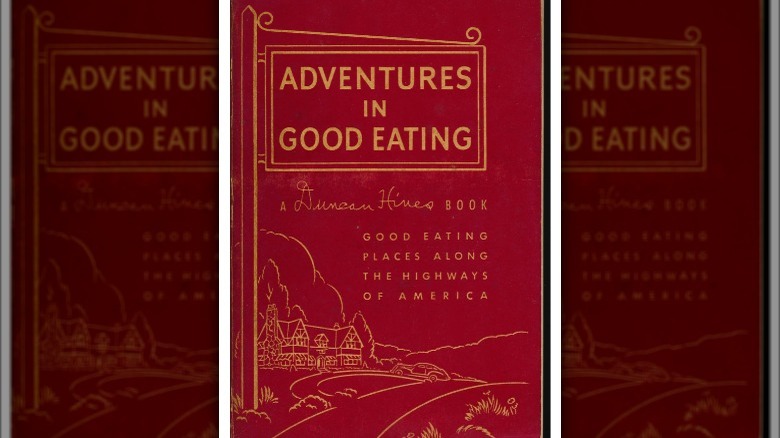

Hines published his first edition of "Adventures in Good Eating," which sold for a dollar apiece in 1936. It would be the first of several guidebooks, published between 1936 and 1947, that would go on to sell two million books, per Slate. The books would make Hines a very wealthy man, albeit a nasty one. His biographer wrote that Hines had a "violent temper." Hines had a nephew that said, "but he quit after about three weeks because his uncle was partial to 'blowing up' at him over usually inconsequential matters."

Unlike the Michelin guides, which featured restaurants if they were determined to be "fine dining establishments," Hines began charging restaurants for his "Duncan Hines Seal of Approval" endorsements. These, Hatchett says, were what made Hines a wealthy man. On top of all that, Hines leant his name to a line of food that included "jam, pickles, mushrooms, sherbet, salad dressing, ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, bread, pancake mix, ice cream, cooking ranges, and coffee makers," according to Slate. By 1955, Hines was bringing in $50 million in royalties, and he made even more when his company was sold to Procter and Gamble two years after that, per Food & Wine. It was a deal that eventually guaranteed that the name of Duncan Hines would live on, even if the memory of who he was as a person would not endure.