The Truth About The Rarest Pasta In The Entire World

We all have our favorite types of pasta, but there are actually over 300 kinds of this Italian staple and you'd be surprised at how different they all are when it comes to shape, texture, filling, and accompanying sauce. But there is one pasta so rare that only a small number of people have ever tried it. Why? To start, it's only produced in Lulu, a village near the city of Nuoro in Sardinia.

The village is home to Paola Abraini, whose family has been making su filindeu, which means "the threads of God," for more than 300 years. It is a mystery as to why or how her ancestors invented this one-of-a-kind pasta, but its recipe and technique has been passed down through the women. Today, only a few people know how to prepare su filindeu: Abraini, her niece, and her sister-in-law.

The thin, thread-like pasta reportedly requires so much time and effort to prepare that for the past 200 years, it was only served to those who underwent a 33-kilometer (21-mile) pilgrimage on foot or horseback from Nuoro to Lulu for the biannual Feast of San Francesco (via BBC Travel).

Why the rarest pasta is hard to make

Su filindeu only involves three components: semolina wheat, water, and salt. But don't be deceived by the short ingredient list. Many have tried to make the elusive pasta, but to no avail.

British chef and cookbook author Jamie Oliver visited Abraini and endeavored to learn how to make the dish under her instruction but had to give up after two hours, saying, "I've been making pasta for 20 years and I've never seen anything like this," per Channel 4. Engineers from pasta company Barilla attempted to replicate Abraini's technique with a machine — and they failed.

Why is su filindeu so difficult to make? It requires a certain intuition that can't be taught. After kneading the dough, Abraini continues working it until it's the right consistency by "understanding the dough with your hands" — something that can take years to master, as she told the BBC. If the dough needs to be more elastic, she dips her fingers into a bowl of salt water. If it needs more moisture, she dips into a bowl of regular water instead.

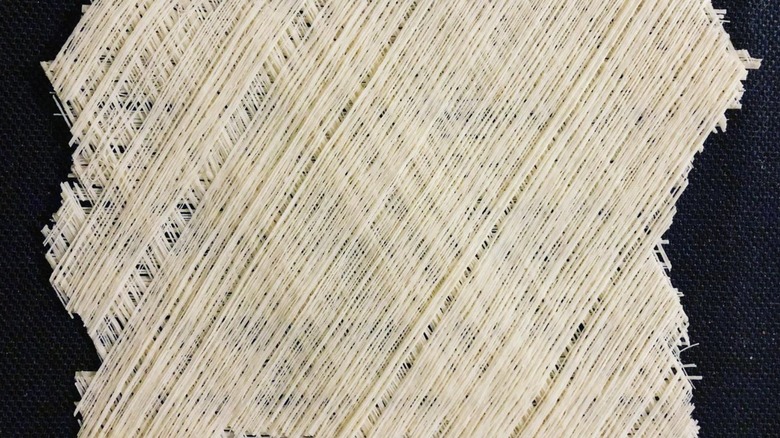

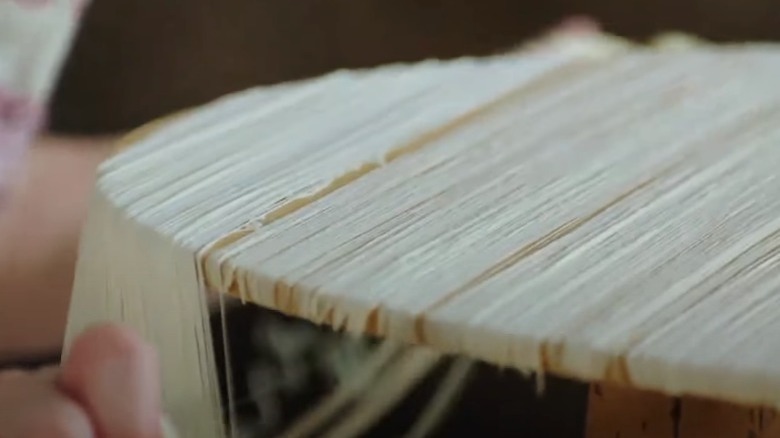

Once the dough has the perfect consistency, Abraini stretches and folds it eight times, making it become thinner with each pull. The result? 256 even strands that are about half as wide as angel-hair pasta (via BBC Travel).

What the rarest pasta tastes like

The thin strands of the su filindeu dough are laid across a round wooden tray as one layer. Another layer is put on top of it at a different angle, and then a third layer. The tray is left outside to dry under the sun, per Saveur.

After several hours, the layers harden into "delicate sheets of white razor-thin threads resembling stitched lace." To complete the dish, Abraini breaks the circular sheets of pasta into strips, which are later placed into boiling sheep's broth and topped with grated pecorino cheese. The pasta dish is meant to be enjoyed as a thick soup for pilgrims who make it to Lulu for the Feast of San Francesco, which is celebrated in October and May, according to BBC Travel.

What does su filindeu taste like? Saveur describes it as "bafflingly fine" noodles in a "potent and pasture-y broth" with a flavor unlike anything else. Australian chef Leo Gelsomino told SBS Australia that the texture of the pasta was "firm but silky and small" and tasted delicious and healing because the noodles absorbed so much flavor while cooking in the broth.

Why the rarest pasta is endangered

Su filindeu is exceedingly rare; in fact, it's one of the foods most at risk of becoming extinct, as Raffaella Ponzio, head coordinator of Slow Food International's Ark of Taste, told BBC Travel. The Ark of Taste is a project that aims to collect and protect culinary products that are in danger of disappearing. Among all the different types of pasta listed under the initiative, no other kind is made by as few people as su filindeu, thus making it the rarest and most endangered pasta in the whole world.

The future of its production is unknown. Out of Abraini's two daughters, one is knowledgeable of the basic technique but doesn't have the same passion and patience for it, and neither of them have daughters of their own. The two other women in Abraini's family who know how to make su filindeu are in their 50s and don't have potential successors among their children who are willing to learn and pass on the challenging recipe.

Seeing how her family's culinary tradition has become such an important cultural touchstone of Sardinia, Abraini attempted to teach girls from other families in Nuoro how to prepare su filindeu, but they were unsuccessful. She eventually invited students into her home, but they left and never returned when they saw how much effort was required to make the pasta, according to the BBC.

The future of the rarest pasta

Despite all this, Abraini has refused to give up on trying to share the secret of su filindeu. She has gone to Rome twice to be filmed making the dish by Italian food and wine magazine Gambero Rosso. Abraini has also been making the special pasta for three local restaurants, thus introducing the dish to non-pilgrims for the first time.

Al Ciusa, one of those three restaurants, won Sardinia's Porcino d'Oro prize for best dish in 2010 with Abraini's su filindeu nero (a black squid ink version of the pasta). At Il Rifugio, another restaurant supplied by Abraini, su filindeu is the most sought-after menu item. "We have people coming from all over Europe just to taste it," owner Silverio Nanu said to BBC Travel.

For now it will take a trip to Sardinia to try su filindeu. Though not many have ever eaten the dish, those who have tasted it are adamant that it should be preserved.