Indian Cooking Essay, By Author Claire Hoffman

The summer I turned 30, I went back home to visit my mother and had a run-in with the law. But the "punishment," so to speak, had less to do with hard time and more to do with learning how to make curry.

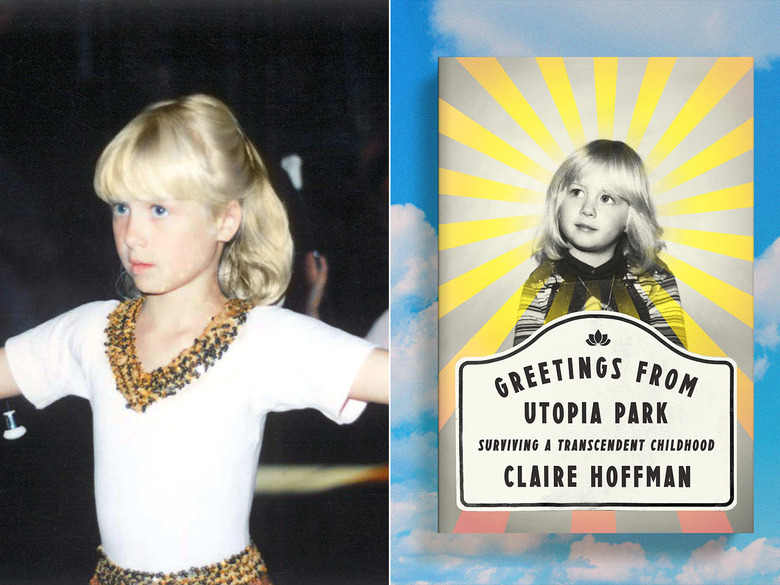

The trip home had become an annual pilgrimage—I had moved away at 17 in a huff of disenchantment. My hometown—Fairfield, Iowa—was the headquarters for the Transcendental Meditation movement, and in the 13 years that I lived in the utopian community, I had felt increasingly restricted and alienated by the all-encompassing beliefs that seemed to pervade every aspect of life (a "correct" way to eat, sleep, dress, park your car and, of course, meditate, determined by our Indian guru)—an experience I recount in my new book, Greetings from Utopia Park.

RELATED The Masala Dosa You Need in Your Life "

In the time since, I'd gone to grad school and become a newspaper reporter, but life in Fairfield had become something I was nostalgic for. I yearned for the eerie silence that took over the town for hours each day as thousands meditated together. That year though, I felt like an overgrown child. I had just quit my job at the Los Angeles Times and broken up with a much-older boyfriend—all of which is to say that I felt like I had brushed up against adulthood and felt bruised and uninterested in the serious life that seemed to be taking form around me.

I let my mom baby me—she didn't mind when I watched Law & Order marathons all day and cheerfully made me my favorite stir-fry. Even though I felt guilty about taking advantage of her young-adult swaddling, I drank it up. It put a spring in my step after months of struggling to make my rent and contending with my own ambition.

And so it was that I ended up at a metal shed of a local bar, where cheap cocktails were served in 16-ounce plastic cups, with a guy friend from high school late one Wednesday night. My friend—we'll call him Tommy—exuded a sort of sexual ambivalence that attracted both women and men like honey. He enjoyed a reputation as a lady-killer, but he and I had an understanding—I loved him, but I kept him far away from the inner doors of my heart.

As we knocked back mammoth gin and tonics, we laughed wildly, regaling each other with stories of the abjection of being young, poor and ambitious. About two hours and 60 dollars later, the world seemed blurry and terrific. It was still 80 degrees at midnight—so we tipsily decided to go swimming.

As Tommy drove us in his mom's station wagon along gravel backroads, we sang along to the radio, as if we were in the midst of our own John Cougar Mellencamp song, living a never-ending summer night in this far corner of rural America.

At the local reservoir, I was immediately hit with the crisp scent of tall pine trees that enclosed us in our own hushed chamber. We stripped off our clothes—we had both spent enough summer nights in the woods to know that the only way to go was naked. I went in first, plowing into the murky waters, and fell back with a splash. I heard my breath inside my own head and looked up at the stars as they trembled, sharp and bright.

I heard Tommy crashing toward me. We stood up to face each other, goofy drunk smiles on our faces—and at that moment, floodlights illuminated our bodies.

A bullhorn crackled, and a voice ordered us out of the water. Disoriented, I tried to cover my body with my hands, both of us snickering and trying to stave off the panic of what was actually happening. Quickly slipping into our soggy clothes, we made desperate pleas to the police officer, none of which worked.

I was slapped with a ticket for public indecency. I didn't know what being 30 really meant, but this felt less like a juvenile infraction and more like an omen of a life slipping off the rails.

I stumbled home on foot, wet and ashamed.

When I rolled into my mom's small kitchen the next morning, hair matted, ankles still muddy, I told her about my ticket. Instead of scolding me though, my mom laughed—which I'm forever grateful for. But I could tell she thought maybe I should spend less time skinny-dipping with the likes of Tommy and more time dating suitable men—which I knew not only because of a deeply intuitive connection to my mother, but also because that day she suggested I take a cooking lesson.

It was the first and only cooking lesson purchased by my mom. She set it up casually as if it were already a done deal—her friend and neighbor, an Indian woman, would come over and teach me how to compose a traditional Indian feast. I felt the subtext: learn how to be a more enlightened lady.

Vaju, my teacher, was a tiny woman, recently widowed. She came over the next day to my mom's small kitchen in a whirlwind of purpose and productivity. I stood to the side, dressed in too-small jean shorts, hair rumpled, nursing a fresh hangover but full of good intentions. My head was bowed: I felt strangely touched, and I wanted my mom to see that I took this seriously.

I listened carefully as Vaju laid out the menu—six dishes (five more than I'd ever cooked at a time). There would be coconut rice (see the recipe), vegetable stir-fry, vegetable curry, deep-fried poori, raita and milk pudding for dessert. As we set out, I felt anxious—my cooking skills were limited to making a mean salad dressing.

But even more than that, I felt guilty about my mom's generosity and wondered if she got me this cooking lesson so that someday I would be a more "ideal" wife. Even though I was naturally rebellious, I felt particularly ashamed of my skinny-dipping snafu with Tommy. But soon these feelings—anxiousness, guilt, suspicion—were pushed to the background as Vaju moved me around that kitchen with precision. A small woman in a sari, she radiated a warm heat, and she took her charge seriously, showing me how to crush the cumin seeds just so and mix the curry spices. I felt my mind go quiet with its worries as I patted the poori batter. When I looked up, I saw my mom in the doorway, beaming at me.

After three hours, we had an incredible buffet of Indian cuisine laid out on my mom's sunny dining room table. We sat down—my mom, Vaju and I—and laughed at the incredible spread as we tore apart the piping-hot bread and dipped it carefully into the vegetables. I told them enthusiastically (knowing full well that I was lying) how easy this would be for me to do again at home—I'd need some staples like curry powder and cumin, but it could be done, I said, as my mind flashed to my spare Silver Lake kitchen, its shelves stocked with salt, cereal and nothing else. I dragged my poori along the plate and wondered if maybe this was the beginning of a new chapter. After we cleaned up, I went off to the courthouse to settle my charges.

These days, I'm a married mother of two in L.A. All anyone wants is chicken fingers. I never made Indian food again.

Claire Hoffman is the author of Greetings from Utopia Park.