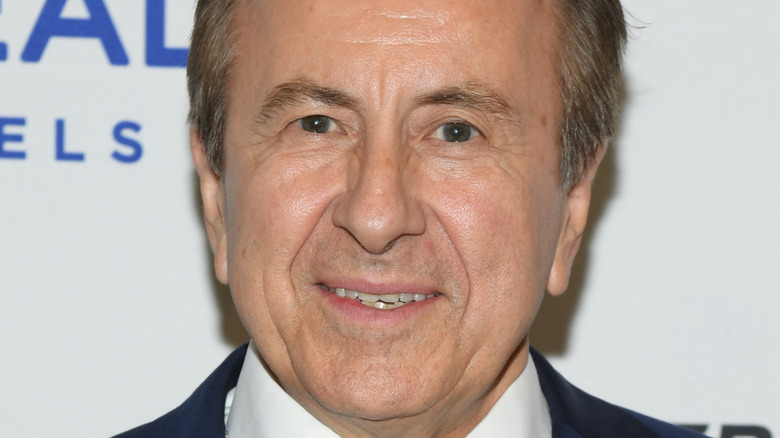

Daniel Boulud On DANIEL's 30th Anniversary, NYC Dining, And Cooking Seasonally - Exclusive Interview

To try to simply list Daniel Boulud's accomplishments is to risk doing him a disservice. He's racked up more accolades in his decades as one of the world's most prominent chefs than it's possible to list in a brief introduction, but we will try. After working his way through Michelin-starred restaurants and fine hotel kitchens as a young chef in Europe, Boulud emigrated to America, taking over the executive chef position at the illustrious Le Cirque. He won the first of his half-dozen James Beard awards while working there, then opened his namesake restaurant, DANIEL, in 1993. His restaurant group has expanded into an international juggernaut over the years, and in 2015, Boulud accepted a Lifetime Achievement Award from the World's 50 Best Restaurants.

Boulud graciously took a break from his busy schedule to talk with Tasting Table in an exclusive interview to celebrate DANIEL turning 30 this year. The two-Michelin-star restaurant is still the crown jewel in his hospitality empire, and the chef happily took a trip down memory lane. He also spoke about his approach to cooking seasonally and staying current in an ever-changing dining scene, and he even shared some cooking tips.

How DANIEL keeps its cuisine fresh

How has the cuisine at DANIEL evolved over time?

It keeps evolving. Te principal success of DANIEL is me, is the team, that we work together. It's the suppliers we have been working with for so many years. It's also New York and our loyal customers. The evolution of the restaurant — the cuisine keeps being very French at the core, but we always embraced seasonality, we always embraced culture, we always embraced technique. Our strength has always been to make sure that our cuisine is relevant, but it's still complex. We are not doing minimalistic cuisine.

We are not doing hyper-designed cuisine either, but we are very conscious of texture and taste and what drives the idea of a dish. Is it an ingredient? Is it a classic sauce? Is it a technique we enjoy bringing back? Because of seasonality, each season, there is a renewal of things that you are familiar with and there is a renewal of things you discover during each new season or a renewal of things you forgot and bring back. There is definitely a cycle of life in our menu that is part familiar and part very new. We will use sorrel every spring, but are we using it in a cold dish? In a hot dish? Are we using it with seafood? Are we using it with salmon, like a classic saumon à l'oseille?

This year, the sorrel, we are using it with softshell crab and passion fruit. Eddy, the chef de cuisine, also was very involved with the development of the recipe, and he felt that there'll be a real contrast between the tannic side of sorrel and the very bright and crisp side of the passion fruit and the crispy softshell that needs tanginess. The softshell is not a very French dish, but it's definitely a New York dish, because I have been cooking softshell for the last 40 years of my life in New York and always prepared the softshell in a very seasonal way, because the window of that particular ingredient is so short.

Redcurrants are another good example. We are falling off spring and starting into summer. Redcurrant is also something we use in many different ways. This time, we are using it with a trout and arugula and young radish. It has a lot to do with the sauce. That's also a dish that is unusual in this combination, but very fresh, very summery, early summer. We'll keep it for maybe a month or two. We have squab. Canard aux cerises [duck with cherries] is a classic French. We love to dig into a classic application and give it a twist. For example, we are using it with squab right now with cherry, and that worked very well as well.

How Daniel Boulud balances flavors

How do you approach pairing these seasonal ingredients and creating dishes?

Layering of seasoning. Seasoning is very important. Texture is very important — taste, harmony. Contrast is very important in the dish because it creates surprise, but harmony, as well, is important because then, nothing really clashes. There are certain things that help keep things in harmony. For example, with the squab, we have a crusted black tea squab. A young guy, Dan Leber, a farmer in Pennsylvania, has been working with us for a long time and developing the best squab we've ever had.

We crossed the squab with the black tea powder. We have also a mix of freeze-dried cherry and amaranth flakes. That creates the seasoning for the squab, and then we use the liver, the heart, the tenderloin. We stuff that into the legs of the squab and we confit that squab.

Also on the dish, we have an onion tart made with pâte sablée. We caramelize cipollini onion with a little bit of mustard coulis, mustard flour, and mustard seeds. We have the salad of amaranth leaf. To finish, we have a cherry and vinegar sauce that has cherry coulis. It's enriched with a cherry coulis and that is very delicate, in a way. There are not too many other garnishes. There is a little bit of collard green that we use as well, because collard greens right now are in abundance and go very well with anything, like roasted birds. When you do your turkey for Christmas, collard greens are always good, or with pork or anything. With that particular dish, with the squab, it's wonderful.

Daniel Boulud's favorite dishes from his career

Do you have a favorite dish in DANIEL's history?

Each season, there is always a favorite dish. It's tough to choose. Many dishes were created because of the opportunity or the seasonality. For example, the Sea Scallop Black Tie in the history of DANIEL, it was created before when I was at Le Cirque, but it was carried on. That dish was created for the holiday celebrations where people put on their black ties and go to galas and celebrations and things. It always remains a classic dish. The Paupiette of Sea Bass wrapped in potato with red wine — we have done 15 different interpretations of that with the combination of the sea bass, the potato, the leeks, and the red wine sauce. Once in a while, we reinvent a new one again.

Recently, we did the salmon baked in clay with a fig leaf, figs, and fennel. The fig, the fennel, the sumac, the fennel pollen, and the salmon are baked in clay. We bring a new interpretation, because it's fig season now. It's salmon season in Alaska, Alaskan king salmon. The fennel is so perfect with that. We often revisit dishes and create new ones.

Why DANIEL has thrived for 30 years

When DANIEL opened, these sorts of fine dining, French-influenced restaurants were very prominent in New York. Over the decades, DANIEL has thrived and many of its contemporaries have closed.

Some of them did, but you see, Jean-Georges, DANIEL, Le Bernardin, are all still open. We remain classic New York establishments. There were some restaurants that were a little bit more trendy, that were very hot, but couldn't sustain success. Sometimes, restaurants don't always have a long lease, and you don't always renegotiate well, because a restaurant has success and the landlord wants to take advantage of it and [they] will raise the rent and that might kill your business.

I attribute the longevity of Danielle to its delivery of cuisine, of service, and of setting. Every 10 years, we completely redo the restaurant, a full refresh and redesign, and we keep maintaining it. We also keep very engaged with our team at staying creative but staying consistent with our quality, with the quality of service and cuisine.

DANIEL and Le Pavillon are New York institutions

DANIEL is a kind of restaurant that you cannot put anywhere. Some restaurants look like they could be in Mexico, in Copenhagen, in Tokyo, in Paris, because they're this new generation of small restaurants that do only tasting menus. DANIEL has never been doing only tasting menus. It's a real restaurant. My life would be easier if I had to do just a tasting menu, but that's not the case. I enjoy the way things are with being able to maintain this excellence at a level that is unique to New York, it's unique to Paris, it's unique to cities that have a demand for this type of restaurant.

There is definitely an interesting demand for new things in New York — for example, Le Pavillon, the new restaurant I opened two years ago. When I arrived in New York City, the only thing people talked about was Le Pavillon, that legendary French restaurant that was in New York and that defined fine dining for 30 years and that also inspired all the other French restaurants to open under that sort of that model or style of restaurant. Doing a new Le Pavillon in New York 50 years after it closed and bringing back this iconic name is exciting.

My Le Pavillon, it's a modern restaurant that still has roots in classic French cuisine, but also it's an American — a real New York restaurant. It was based on the fact that I wanted to create a restaurant that was very French and very New York. The name of "Le Pavillon," the history and all that, there was nothing more French and more New York. Today at the Le Pavillon, is there a lot of French in it? Maybe not, but there is a certain respect for tradition, there is a respect for a type of cuisine that represented its era.

DANIEL is even more New York. It's very New York as well, like Le Pavillon, because DANIEL was born in New York. It's a New York restaurant, but by definition has French DNA.

Boulud loves exploring cuisines from around the globe

You keep on exploring new things. You opened Joji, your first omakase restaurant. Martha Stewart came to Joji and learned how to do sushi a little bit. How were her sushi skills?

That was fun. I always dreamed to open a Japanese restaurant, and this opportunity came to be able to do it at One Vanderbilt, where our partners own Le Pavillon with us, and I found that very fascinating. I'm not a sushi chef either. I have enough knowledge to pretend that I can do it on my own, but in partnership with Josh and the team there, we created something very unique.

Are there any other cuisines that you're interested in exploring in future restaurants?

I love Vietnamese cuisine [and] Italian cuisine. I have a restaurant called Boulud Sud, and Boulud Sud is flirting with and embracing five different cuisines, at least. There is the French Provencal, then there is the coastal Italian cuisine, there is the Greek, there is the Middle Eastern, so Turkish, North African, Israeli, and Lebanese cuisines. There is the Spanish cuisine. Those cuisines to me are quintessential for the Mediterranean.

At Boulud Sud, we have manakeesh, which is not a pizza. it's basically a flatbread pie, the manakeesh that we do in a more Turkish style. We do tagine and we do gambas al ajillo. We do Italian pasta as authentic as any pasta restaurant. We do also wonderful Provencal dishes and mezze. That shows how much we enjoy embracing other cuisines.

Exploring global cuisines, continued

I have written a book called "Braise." It's a journey around the world of braising, and every culture, every cuisine has a way of braising things. Braising sometimes requires a lesser cut. You don't need filet mignon to braise. You don't need sirloin. You braise with neck, you braise with shanks, you braise with ribs. When you look at Mexican cuisine, when you look at Indian cuisine, they always use affordable cuts and make delicious food out of it.

Cafe Boulud was recently celebrating its 25th anniversary in New York. At Cafe Boulud, the menu was always divided into four muses. Those four muses, those four menus are my inspiration and maybe the best reason why I love to be a French chef in New York and in America. One of them is La Tradition. La Tradition is based on French traditional cuisine. There is always an offering of dishes of that.

There is La Saison, it's a menu that is spontaneous, that is seasonal, that is market-driven, and that can be French in inspiration, that can be local American and all that. Then there is La Potager, which is a vegetarian menu. I remember 25 years ago doing a menu just of vegetables. It was really the beginning of having more vegetarian food on menus. Vegetables always play a big role in my own personal diet.

And then, there is the Menu Voyage, Le Voyage. I remember from the time Andrew Carmellini was the chef at Cafe Boulud when we opened, then Gavin Kaysen was the chef at Cafe Boulud, and then Aaron Bludorn, we all enjoyed together creating menus that had nothing to do with French cuisine. We had a Mexican menu. We were traveling the world. We had Japanese, we had Vietnamese, we had Indian, we had North African, we had Brazilian, we did New Orleans, for example.

We will really look at traditional cuisine and really respect the importance of a classic recipe and create our own and refine it and make it a little bit more interesting. It was also an opportunity to include our team in the kitchen, because we always had a chef that was from Vietnam and had his grandmother cooking for him, or a chef from Korea, or Japan, or Mexico, you name it. Every time we had a cook from somewhere else, that could be a good inspiration.

Daniel Boulud's last meal

If you could choose your final meal to eat on Earth, what would it be?

It should be at DANIEL and it should be like when I celebrated my 50th birthday. I had a friend that offered to bring the wine and I said, "Okay, I will bring the food." We had maybe 24 friends between the food and wine world, and I had 16 chefs that used to work for me, and they each made an amazing dish for the celebration. For my last meal, I would like to do an encore of this.

My hope is to do it again when I turn 100 years old, because this one was for my 50, which I felt was really my mid-life celebration. For my full life celebration at 100, it'd be good to bring the talent I had the opportunity to nurture, to mentor, to train, and to grow with and to have them cook for me and my friends as a gift to life and to friendship and to what we've done together.

Boulud's friendship with Jacques Pépin

One person you're dear friends with is Jacques Pépin. Has he ever given you any advice that you've taken to heart?

I have some great memories of Jacques Pépin. What's interesting is that I've always been fascinated by Jacques, because he came before me and he's my encyclopedia of French fine dining in New York, because he was working at Le Pavillon when it was the old Le Pavillon. When I opened the new Le Pavillon, during staff orientation, I invited Jacques to come as a speaker. The owner of Le Pavillon at the time was not a nice person, and I don't think Jacques kept a good fond memory of that guy. He didn't like it.

There was a lot of rivalry between the maitre d's and Jacques at the time, a little bit rivalry or opposition. I've known [Jacques] for 40 years and it never ceases to please me the way he thinks about French cuisine, the way he communicates about French cuisine. He never ceases to impress me by inspiring so many generations and inspiring kids today. At his age in his late 80s, to be able to inspire kids of French cuisine — the biggest lesson with Jacques is that he has known how to make it simple, make it easy, make it friendly, and make it delicious.

Jacques is the quintessential chef. I love to watch him in his little cooking classes he does, because he is a chef that was born with a certain generation. I've learned those practical techniques that are still relevant today but many people don't know. Today, people are learning in a different way, and we are teaching a different way of doing things. Jacques is so pragmatic, he's so knowledgeable, and Jacques knows how to take the fuss out of things and make it homey, friendly, delicious, and easy.

The competition technique for a perfect omelet

I saw a video of you cooking an omelet where you cooked the shell of the omelet and the scrambled eggs inside separately. Did you come up with that?

No. This technique, sometimes it's applied in competition. The MOF does chef competitions, and everybody is doing the same dish. It's not like "Iron Chef," [where they would tell you] "Here is the octopus. Now do whatever you want with it." Everybody has very strict guidelines on how to cook an egg, and they have to do it to perfection. Sometimes chefs use this technique that will combine the basic technique of an omelet and then the basic technique of scrambled eggs and put the two together. It's called an omelette fourrée, and "fourrée" means "stuffed." Stuffed omelette. It is not practiced in restaurants or anything like that, and it requires a little bit of a technician to be able to do it right.

Because you have to do the two things at once, right? But I imagine that both components of the omelet are then perfect.

That's true.

You can dine at DANIEL at its location on 60 E. 65th St. in Manhattan Tuesday-Sunday from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m.

This interview has been edited for clarity.