9 Telltale Signs On The Label That Identify Good Canned Tuna

From the time it was first offered in the early 1900s, canned tuna has become a popular ingredient all around the world. Canned tuna is versatile and convenient. It can be enjoyed as a ready-to-eat snack just by opening the can, or it can be used in a variety of delicious recipes. It's also more affordable than fresh fish and has a much longer shelf life. And just like fish in general, it's notable its high levels of protein, vitamin D, vitamin B12, selenium, and heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids, which protect against cardiovascular disease.

Despite its popularity, there are concerns about consuming tuna as the shadowy side of the fishing industry and mercury contamination have been increasingly reported. Many people are concerned about the environmental impact of certain fishing methods, overfishing, by-catch of other marine animals, the risk to endangered species, and contamination from fish farms.

Consumers can rightly feel confused about how to make good choices in the grocery store, or even whether to buy tuna at all. If you've never inspected canned tuna labels before, there are some telltale signs printed on them that can give you information about how the tuna was caught and its nutritional properties that can help make these decisions easier.

Wild caught versus farmed tuna

The term "wild caught" indicates that the tuna was caught in the ocean rather than coming from a fish farm, where tuna are raised in captivity. There are certain differences between wild-caught and farmed tuna to take into account before choosing one kind or the other. Wild tuna are free animals that live in the ocean with no restrictions on their natural movement, migration patterns, and lifespan (unless they're caught in a fishing net). Farmed tuna are either hatched in captivity or, in a method known as tuna ranching, are caught young and moved to tuna farms. In either case, they live in a large floating cage for up to a year before being processed.

From a health standpoint, wild tuna, because of their freedom to swim more, are leaner than farmed tuna and have less saturated fat. On the other hand, farmed tuna tends to have more omega-3s because of the fortified feed they eat. Some people question this feed, which can be natural or artificially enriched with the aim of fattening up the tuna as much as possible.

Most of the controversy between these types of tuna is about sustainability. Wild tuna is not a known source of ocean contamination. Farmed fish are kept in concentrated areas where their waste builds up instead of being dispersed over wider areas of the ocean, and this buildup can contaminate water sources on the coast. Chemicals are also used to ward off disease and algae.

How the fish was caught

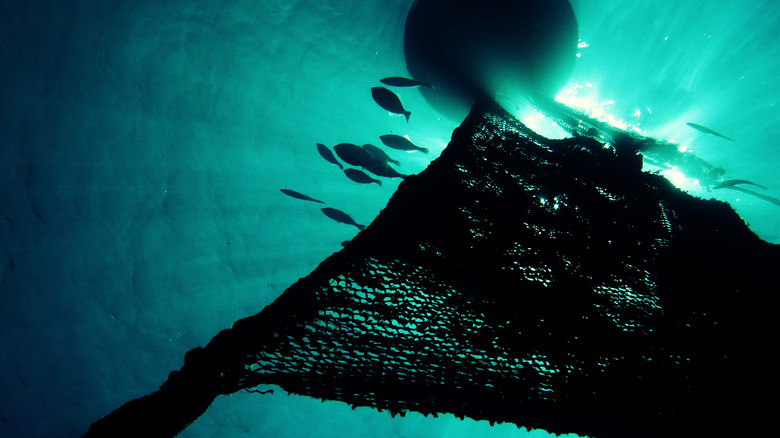

Tuna can be caught in a variety of ways, some of which are more sustainable than others. Gillnets are large nets a few miles long that hang in the water and trap a fish's head and gills when it swims into it. Longlines are miles-long fishing lines with baited hooks attached at regular intervals. Purse seine nets are large nets that are wrapped in a circle around a school of fish after it's located and then pulled closed like a drawstring purse. Gillnets and longlines, and sometimes purse seine nets, have high by-catch rates, meaning the nets or lines not only catch tuna but other marine animals like sharks, birds, rays, turtles, and other species of fish, as well.

Pole and line fishing is the most environmentally friendly, with troll-caught tuna coming in second. Pole and line means that each tuna is caught one at a time by a person using a single fishing pole and hook, making it easier to target tuna and prevent by-catch. Trolling also uses one hook for each fish, but many lines are installed on the back of a boat. Although they are the least invasive, even these methods have some drawbacks — they're heavy on fuel, and pole and line fishing can use unsustainable bait.

If the label doesn't indicate the fishing method, you may want to steer clear of it, because the manufacturer probably doesn't want to reveal it. The company won't advertise the fact that its product was caught using gillnets, for example.

Dolphin safe certification

Dolphin-safe tuna labeling, which indicates whether dolphins are caught with tuna, began in the 1990s in the United States and kick-started an often emotional awareness in many people of where their tuna comes from. Dolphins are at risk because they are like flashing road signs pointing out where yellowfin tuna schools are. This kind of tuna is often found swimming near dolphin pods in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. After locating the dolphins, some commercial fishing boats use purse seine nets to surround them in order to get a huge haul of tuna. The price? A huge haul of dead dolphins too.

Scientist Sam LaBudde brought this matter to the world's attention when he went undercover on a commercial tuna boat in 1987, filming shocking footage of dolphins drowning in nets. Tuna boycotts from outraged Americans quickly led to the start of dolphin-safe labeling. The Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act was established in 1990 to regulate this labeling and verify that commercial vessels were following the rules.

While buying dolphin-safe tuna helps, it unfortunately doesn't address all the concerns with this product. Dominant American tuna brands have been in the news for falsely labeling cans as dolphin-safe, and thousands of dolphins continue to be killed every year, as highlighted in the Netflix documentary "Seaspiracy." Even if no dolphins were harmed, the label doesn't reveal if the tuna itself was caught ethically or if other marine animals were caught as by-catch.

MSC certification

The blue MSC label on tuna cans indicates whether the fishery that caught the tuna has been certified by the Marine Stewardship Council, an international nonprofit organization concerned with safeguarding the oceans and preserving seafood levels. Any fishery that catches wild fish or seafood can be certified, although no fisheries are compelled to comply as participation is voluntary. The label shows compliance with the MSC Fisheries Standard, which establishes if the fishery uses sustainable fishing practices, and the assessments are made by independent certifying parties.

The assessors primarily look for three things. The first is whether the fishery avoids overfishing in order to leave sustainable levels of healthy fish in the ocean indefinitely. The second is if the fishery reduces undesirable environmental impacts not only on the species caught but on the entire affected ecosystem. The third consideration is how well-managed the fishery is in terms of following applicable laws and flexibility in the face of new environmental concerns.

The MSC label on tuna cans can help consumers understand if the product was sourced using more environmentally-friendly methods. While considered by many to be the best ocean safeguard currently available, even this labeling is involved in controversy. Some critics have called the certification misleading after reports surfaced of endangered right whales getting trapped in fishing gear or hit by fishing vessels certified by the MSC.

FAD-free

Cans labeled "FAD free" contain tuna that was caught without the use of a Fish Aggregating Device (FAD). This device is either a natural object like a log or a synthetic construction that floats on the ocean surface with the purpose of attracting groups of fish. Many marine species like tuna, especially skipjack tuna, are attracted to the shadowy area cast under floating objects because they are a source of safety from above-water predators and a source of food when other species like mussels grow on them.

FADs make it easier to catch more tuna because the devices are equipped with satellite and GPS technology, which show the location of each device, and with sonar, which reveals the number of fish gathered underneath. Fishing vessels, usually purse seine boats, will travel to the locations with the most fish, thus increasing the efficiency of the vessels.

However, the environmental impacts of FAD-caught tuna are cause for concern. Since the nets are cast in a circle around the whole area, the by-catch increases significantly. In fact, Marine Policy reports that FADs are 2.8 to 6.7 times more likely to trap by-catch like sea turtles and sharks than fish caught without the devices. Overfishing is also a concern since it's easier to catch fish faster than the species can naturally reproduce and maintain a healthy population level. Lastly, abandoned devices, known as ghost gear, continue to trap marine life and contribute to increasing levels of plastic ocean trash.

Mercury considerations

The toxic metal mercury enters the air from industrial fossil fuel pollution and then rains down into the water fish live in. Traces of it are found in most fish, but some types contain more than others. Concentrations are highest in the bodies of large and predatory fish, who have simply spent more time accumulating mercury by eating smaller fish lower in the food chain. The FDA includes bigeye tuna with other large fish like king mackerel, shark, swordfish, and tilefish as high mercury choices to avoid.

Canned tuna is usually one of two kinds, and the label will say which. The first is albacore tuna, which is called chunk white or solid white albacore on the label. The second is chunk light, which is usually skipjack tuna, a smaller variety. Albacore contains almost three times more mercury than light tuna, so selecting the latter is a strategy to avoid ingesting too much.

How much tuna is safe to eat each week? The FDA recommends that adults, including pregnant adults, consume a maximum of 12 ounces of canned light or skipjack tuna a week. The recommended limit drops to 4 ounces for albacore or yellowfin tuna. Children should only eat two servings (from 1 to 4 ounces depending on the child's age) of canned light or skipjack tuna a week and avoid the other species.

Water packed versus oil packed

Canned tuna labels will specify whether the tuna is packed in water or oil, but does it really matter which one you choose, and is oil-packed tuna worth the higher price tag? Neither kind is better or worse than the other. The choice lies in the tuna's intended use. Water-packed tuna is a good choice if you're planning to drain the liquid anyway or if you will use the tuna in a recipe that calls for a variety of spices or flavorings. This tuna is more of a blank canvas for creating your own flavor.

On the other hand, there are reasons to choose oil-packed tuna. It's perfect for recipes that call for oil, and it has a richer flavor and moistness that make it ideal for the times when tuna will be eaten alone. Although oil-packed tuna is more flavorful in general, there are gourmet and luxury tuna brands that really take tuna to the next level. Brands like Costa Rica's Tonnino oil-packed tuna fillets, Spain's Ortiz Bonito del Norte oil-packed white albacore and, both from Italy, Rio Mare yellowfin tuna in oil and Callipo jarred tuna fillets in oil, are decadently delicious and worth trying at least once.

Water-packed tuna has fewer calories and lower fat content, with 66 calories and not even 1 gram of fat per half-cup serving. Tuna packed in oil has 145 calories and 6 grams of fat in the same size serving.

BPA, expiration date, and the can itself

Tuna sold in cans is subject to the same safety considerations that apply to all canned foods, and carefully reading the label can help you identify these. Look for BPA-free labeling to avoid ingesting bisphenol-A in your tuna, a harmful industrial chemical linked to cancer and disruption of the endocrine system. Unfortunately, not all companies have been transparent about what they are using instead, and there is some controversy over the safety of BPA alternatives like bisphenol-S.

Every can will be stamped with an expiration date, so make sure to check this date to avoid consuming unsafe fish. Canned tuna has a rather long shelf life of three to five years, so as long as the cans are stored correctly, the expiration date isn't a pressing concern — but the cans will go bad eventually. For the best results, store them away from direct sunlight in a location with a temperature between 50 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit, like the kitchen pantry.

Inspect the can itself before taking it home from the grocery store. Discard any dented or rusted cans because the seal may have been damaged, allowing harmful bacteria to enter. Botulism, a dangerous form of food poisoning, is rare but sometimes present in canned goods, so absolutely reject any bulging or leaking cans or any that hiss or even explode while you open them.

Species

Words on the label identifying the type or species of tuna can help you decide which tuna is ideal for your recipe. There are actually more than 12 separate species of tuna living in the oceans. Bigeye, bluefin, albacore, skipjack, and yellowfin are the five kinds most commonly sold in the United States. Canned tuna may also be identified by the more generic terms "white" and "light." The difference between white and light tuna is that the term white refers to albacore tuna only, while light tuna is usually skipjack or yellowfin tuna or a combination of the two. "Chunk light" just means the light tuna is not a fillet but smaller pieces packed in the can.

Any of these kinds of tuna can be a good choice. It depends on how you intend to use the tuna, health considerations like mercury levels, availability, and budget. Albacore tuna is a firmer, meatier choice that holds together well if that's important for your recipe. It has a more neutral flavor for those who don't want a strong tuna taste. Skipjack and yellowfin tuna have softer, more flavorful flesh and a strong fishy taste. Yellowfin tuna is often found in gourmet oil-packed products and is prized for its fantastic flavor. In terms of nutrition, the health benefits of skipjack tuna (such as higher selenium levels) make some people reach for this species, and the FDA recommends fewer servings of albacore tuna every week than light tuna because it contains more mercury.