Aaron Franklin Wants You To Make Better At-Home Barbecue This Summer - Exclusive Interview

Aaron Franklin is the master of barbecue. Franklin Barbecue, the Austin restaurant he started with his wife, Stacy, ranks number one in Tasting Table's recent roundup of the best barbecue restaurants in Texas. But don't just take our word for it — Franklin's world-famous brisket has garnered praise from the likes of President Obama, the late Anthony Bourdain, and the loyal following of barbecue enthusiasts who travel from thousands of miles away to wait in an hours-long line, hoping to sample the best smoked ribs, pulled pork, turkey, sausage, and of course, brisket.

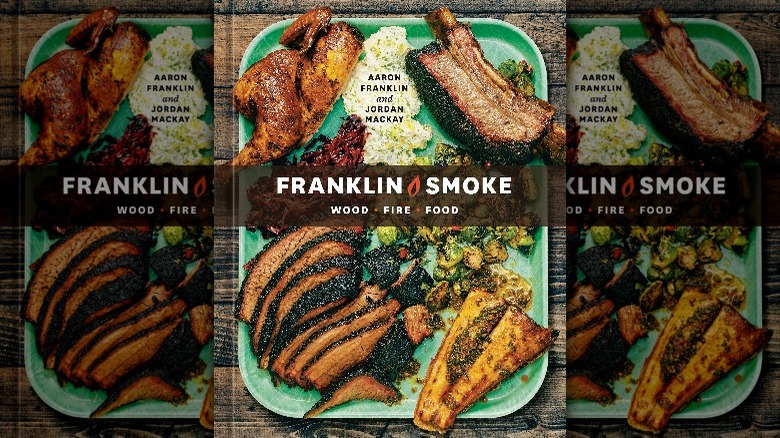

In 2015, Aaron Franklin became the first pitmaster to be recognized by the James Beard Foundation Awards when he took home the title of Best Chef: Southwest. In 2019, he was further honored by James Beard for his legendary barbecue. To help you emulate Franklin's mastery at home, he's written three cookbooks with his collaborator, Jordan MacKay: the New York Times bestselling "Franklin Barbecue," "Franklin Steak," and the newly released "Franklin Smoke."

We recently connected with Aaron Franklin to talk barbecue, slow cooking, and the most common mistakes folks make with brisket. Speaking exclusively with Tasting Table, Franklin shared his barbecue guidance for foods that aren't meat, his favorite everyday ingredient for the delicious steak, and a few tips to enhance your at-home cooking.

Why barbecue isn't just about meat

"Franklin Smoke" expands the Franklin Barbecue universe by focusing on barbecuing foods beyond brisket and steak, including vegetables, birds, fish, and shellfish. What are the differences or similarities in cooking techniques for non-meat items on the barbecue?

The book is intended to focus on how to utilize an entire fire, from beginning through initial combustion, through hot coals, through all the stages in the lifespan of a fire. If you think about it like that, the cooking doesn't change between meat or vegetables.

Either way, you have to go through the same process. If you go to the grocery store and you're looking for a steak, you have to ask yourself: Is it a big, thick steak that's fatty, or is it super thin and lean? Then you collect the data as you would the same way for vegetables or oysters or a thin fish or a big fish. The idea is that you're constantly building your bag of tricks to become a better cook so that you'll start to understand what kind of heat [whatever you're cooking] needs.

If you want a smoky fish that's pretty fatty, that would tell you I want to build a fire like this. If you're going to do a thin steak or maybe broccolini or something like that, you need really hot, intense heat. Then you can build the rest of your menu off the lifespan of the fire ... The technique is [the same] across the board for anything you're cooking. It doesn't matter what it is. Food is food, pretty much, but to know how to treat different foods is cool.

Franklin's favorite underrated cut of beef

What's your favorite underrated cut of beef, and how do you prepare it?

We talked about it a lot in ["Franklin Smoke"] and now it's harder to find, but a bavette steak is one of my all-time favorite steaks. That's a lower sirloin. Here in the States, it's called flap steak or flap meat at the grocery store. It's a nice, lean piece of meat. It's got a texture more like a hanger steak, but it's fairly inexpensive.

[Since] it's lean, it doesn't have a lot of fat that doesn't render out. It's got a good, fibrous texture, like a hanger steak or maybe a flank. It's got a pretty good minerality too. It takes flavors well, it's easy to cook, and it's smaller. I like smaller steaks — I'm not going to sit there and eat a four-pound steak by myself; that's way too much.

Bavettes also take on smoke nicely. You can grill them really well, but normally, if I cook them, it's at home with a little bit of butter in a skillet. They work great for that. It's a versatile piece of meat.

Franklin's favorite everyday ingredient

How do you choose between a rub versus a sauce for your meat?

It depends on how you're going to cook. I usually use salt on everything. I'll use a couple of different kinds of salts for different things. I typically cook at a pretty high heat, and usually, rubs burn. Rubs are for slower cooks — if you're smoking ribs or brisket or something like that. I keep it pretty simple ... if I'm doing steaks, it's almost always salt. Salt's great. It pulls out the natural flavor that's already there. I don't like to make things taste like what they're not.

We have a couple of different seasonings in ["Franklin Smoke"]. One's a riff on Lawry's, which is freaking delicious. Everyone loves Lawry's. The other one is steak seasoning, which actually is super good and it's more of a beef ... It's vegan and MSG-free, but that's good on even mushrooms. It's mostly mushroom powder that's on there. It's like Maggi umami — works great in sauces also. We use it at the other restaurant on the fries ...

If I was going to air dry some meat and then slow cook in an oven to par-cook it, I would [use] that steak seasoning. But for a more intense heat, like in a skillet or on a straight grill, that stuff would burn, so I typically just use salt. I don't have a lot of stuff at home since we never cook, but I always have salt.

One of the sauces in your book caught my eye — the rye barbecue sauce. Why rye instead of bourbon?

I love rye. I celebrate the dark spirits. Rye's a lot more peppery; it's a lot less sweet because of its mash bill. Rye goes with the smoky grilled flavors a lot better. It has these pepper notes and vanilla notes depending on what kind you get. In the book, we used High West Double Rye, which is my standard around the house for normal drinking and cocktails and stuff. It's got a fair bit of sweetness on it, but it complements the smoke and the pepper. Cherries are a natural fit for that. I don't know; it sounded good.

Aaron Franklin is ready for cooking innovation

Do you have any guidance for home cooks who have less time on their hands if slow cooking isn't an option?

If you're into slow cooking but you don't have time, maybe slow cooking is not your thing. There's no substitution for time and labor. There is technology out there for pellet cookers and things like that, [which] definitely have a place in this modern world. I don't own any of them, but the technology's come a long way. The food quality people are capable of achieving off of a pellet cooker, specifically — or other technology-driven cookery — is way better than it's ever been.

If you want to take shortcuts, it's okay, but you always have to know that your potential for the best thing you could possibly eat is going to go down a little bit. You've got to choose your battles. A lot of people don't have room [for a smoker], and a lot of people don't have the time. The older I get, the less excited [I am] — aka not excited at all — to stay up all night and stare at a fire. I've done it way too much over the years. A pellet cooker sounds more exciting.

How to achieve desirable flavors without a smoker, sous vide, or pellet cooker

What do you recommend for home cooks without access to a smoker, sous vide, or pellet cooker who want to achieve something similar on a gas grill or an oven?

You can't make a fake fire. People claim that you can cheat on a propane grill with wood chips and stuff like that, but if we read the books and look at clean combustion and combustion temperatures and how fires work, you'll see that you're robbing the combustion of what it needs to burn cleanly. You can't burn a real fire in an oven; that's not safe. [When you fake it], you change the chemical structure of that smoke — we'll call it smoke — but it doesn't taste anything like what you would achieve from a real fire. It's fun and exciting to mess around, and I realize it can be challenging to have a barbecue pit or to dig a hole in the ground and do it super old school, but it's hard to get the same flavors [if you don't] ...

If I wasn't able to smoke something on a smoker or able to fire up a grill outside, I would probably slow roast in an oven and bring other flavors in like garlic, or maybe dry-brining for a big roast before cooking it down ... [I'd go with] a more of a traditional style of cooking, like making stock, because you can develop some of the same flavors inside with a good Maillard and get those deep, roasty flavors.

If you're roasting bones and going through all the steps and getting a little more Frenchy with it ... you won't get the smokiness, but you can get the same appeal out of something. [With] a nice grandma pot roast that's been seared and cooked in veal stock — not that my grandma made veal stock by any means — you can get the same, unctuous, "Oh my God, this is so good" that you might be able to achieve on a smoker with a long cook. It won't have that smokiness, but chemically, you'll still get the amino acids that work out together.

Again, you've got to pick your battles. A long time ago, I didn't have a barbecue pit. I wanted one so bad; I was always trying to figure out how to build something or what I could do, [whether] I could cook on a Weber or get some cinder blocks and make a brick thing in the backyard. I did a bunch of that stuff because I didn't have a cooker and I wanted one so badly. Maybe it's an excuse for some people to get creative. Maybe you'll land on something you really like.

If you think about life — and cooking — that's truly as basic as it gets. Throw some salt on something and cook it on a fire. If you can get it hot, you should be able to cook it. I wouldn't necessarily cook on pine pallets and Ikea furniture or anything like that, but you can build a fire.

Franklin's advice on your biggest brisket mistakes

What are the biggest mistakes folks make while cooking brisket?

The two things I hear more often than not are people not having good expectations of how long it takes, but also not having a good game plan. ... Be realistic about it. be realistic that certain parts of the cook are going to happen at certain times, and be ready for it. Be in-it-to-win-it and organized.

If somebody is cooking on a fire, the other thing that I hear a lot about are people whose temperatures are up and down. They struggle with fire management ... [You have to] be considerate of the size of the wood you're using — if it's wet, if it's dry, if it's Ikea furniture, whatever your fuel is. If the temperatures are up and down, it's pretty likely that your firewood is too big, so it's robbing energy from the fire to get to a combustion point. Then, once that log catches, it's way too hot, and you're always up and down trying to fight it: "Oh, it's too hot. Close the door. Open the door. Take a log out. Squirt some water on it. Splash this on it. Blow; it's too cold."

Practicing before you start cooking can be a good idea. I don't do this very often anymore, but back in the day, if I was doing an event on a strange cooker or out in a field somewhere — with weird firewood, [a] weird cooker, a hole in the ground, maybe a cinder block pit, maybe I'm in a different country — I would show up early, get some extra firewood, and practice before I actually got the food on. I would try to collect some data to help me out later on so that I [had a] feel for the firewood. If you're in a high elevation, if you're down at sea level, if it's humid outside — all these variables totally matter. But if you practice a little bit and overanalyze and collect the data, it could help you out exponentially.

The key to keeping your meat moist

Do you have any recommendations for how to preserve moisture when cooking meat?

Different cuts and different meats and different grades of meats definitely affect if you would cook low or if you would cook hot and fast, or if you're going to cook medium rare, or if you're going to cook a brisket to 200-plus degrees to get the collagen to break down. Those are two opposing views and two different ways to cook.

[With] steak, the worst thing you can do is overcook it. You can always put it back on [the grill]. It's very rare that somebody's like, "This steak's too raw," if it's warm and it's cooked right. But different steaks require [different preparations]. You can cook a big, fatty ribeye way more medium than you could a filet. They all cook differently. They all have different thicknesses, and fat conducts heat differently than protein. Is it a low heat for a longer time? Is it a high heat for a shorter time? Was it cold when it went on? Did you temper it? There's a whole bunch of stuff going on there ...

People typically cook brisket at too low of a temperature. The collagen never gets a chance to break down and get tender, so it feels tight. When that happens, you get this chalky, tacky texture out of it, so it feels dry to the tongue. It's almost tannic in a weird way. It's not tannic at all, but it has that mouth sensation that's stringent, like, "Ah, it's dry."

If you're not cooking hot enough or fast enough, you're running out of fat because fat renders at a lower temperature and the collagen breaks down. You've got to make these two timelines line up at the end. If you don't, you end up possibly with a brisket that took way too long to cook, and it's dry because it rendered out all this fat, but it never actually got tender. You've got shoe leather at that point. You have to know when to push it and know when to hold back. About 20 pages of "Franklin Smoke" is that brisket recipe — not really a recipe; it's more of a stream of consciousness. It's lengthy, but all the information is in there.

The difference between beef grades

There are many different grades of beef: Select, Choice, Prime, Wagyu for premium cuts ... Do you think there's a measurable difference in taste between them?

Absolutely. There's a huge difference. If you look on the low end of the spectrum, you've got maybe No-Roll or Select from commodity beef, which are young, fast-growth cows. Their fat didn't build right. They've got subcutaneous fat, not good marbling. It takes time to develop flavor and it takes time to develop good fats.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you might have older cows that were pasture-raised — they had a nice life, they smelled the flowers under the tree out in the field and ate plenty of grass and got sunshine and all that stuff. Maybe they're older, so they've had time to develop good marbling, and they've been happier. They weren't pumped full of chemicals to make them grow abnormally fast.

The bottom end is all the commodity stuff with growth hormones. As your grading increases, the animal health increases. The way we're treating our earth gets better — the way it replenishes the soils and the grasses grow naturally. All that stuff increases as you move along the spectrum. On the top end, you have a delicious animal. But on the other end, there's a huge difference in how the fats grow. [Whether] an animal was stressed when it was harvested, or if it was happy until it had one bad day, which is what we all want — that's what I want, at least — that makes a huge difference.

When I'm in a grocery store, I can look at meat and be like, "Oh, that was a stressed animal." You can tell [by] the way the fibers tense up. All these details, they all stack up. But you can only afford what you can afford, and some of the stuff out there gets crazy expensive. I am totally sensitive to that because things are expensive. But if you can afford something that's nice, you definitely get what you pay for. You're also eating an animal that was treated ethically, so it's going to taste better.

We don't even need to get into genetics, but different breeds taste different, and that stuff totally matters. Marbling does matter, but it's also how that marbling came to be. You can't fake it. It's the same as with the fire — if you want a nice steak, you can't fake it.

When you say you can immediately tell when a cow is stressed, what do you see?

It could be the color of the muscle. It could also be how the fibers look. Almost everything in a grocery store is from a stressed animal. They release so many hormones when they're fearful; that definitely affects how things rest and settle down. It's sad. That's not cool.

Barbecue's intersection with the larger world of food

You've opened two restaurants in addition to Franklin Barbecue — Loro, an Asian smokehouse, and Uptown Sports Club, a Louisiana-inspired restaurant that serves po' boys with bread that comes directly from Louisiana.

Heck yeah — we're trucking to Leidenheimer [for French bread] once a week.

How do you see the world of barbecue intersecting with these other culinary traditions?

That's part of the evolution of barbecue. It's clearly a trend for barbecue to cross over into other genres. It's awesome because the basic stuff that we do here at Franklin Barbecue is so rooted in '40s, '50s German-Czech meat markets and that spread that happened post-World War II. It's pretty basic, but we try really hard to make it the best we can and to sweat the details. It's cool that barbecue has been accepted as more of a chef-y thing. It has actually worked its way into people's dialect on food and is gathering all the influences — and also bringing it back full circle, back to African cuisine and stuff.

There's so many great restaurants [and] so many great cooks out there right now making fun combinations. Fire cooking has been around forever, and every culture has celebrated that in one shape or another. I look at [what's happening now] as part of the evolution of food.

Franklin Smoke is now available for purchase here. Keep up with all things Aaron Franklin and Franklin Barbecue on Instagram.

This interview has been edited for clarity.