How Doreen Fernandez Helped Filipino Food Get The Respect It Deserves

Filipino cuisine may be synonymous with chicken adobo today, but in 1975, food writer Doreen Gamoba Fernandez decided she would try and argue why this should not be the case. Instead she proposed an alternative national dish in her essay, "Why Sinigang." She wrote: "Rather than the overworked adobo (so often identified as Philippine stew in foreign cookbooks), sinigang seems to me the most representative of Filipino taste."

She adds: "We like the lightly boiled, slightly soured, the dish that includes fish (or shrimp, or meal), vegetables and broth. It is adaptable to all tastes ... to all classes and budgets ... to seasons and availability ..."

Like so many of her essays on the country's once-overlooked cuisine, Fernandez's observations did not come lightly. Instead, they came from a place of understanding, honed by years of scholarship and observation. Aside from writing a regular food column for several Philippine publications, she also taught at the prestigious Ateneo de Manila University for three decades, eventually chairing its English and Communications departments. Another career highlight: Her presence at the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, where she presented papers on street food in 1991, and an in-depth look at Philippine flavorings, encompassing all four taste sensations: bitter, sweet, salty, and sour in 1992.

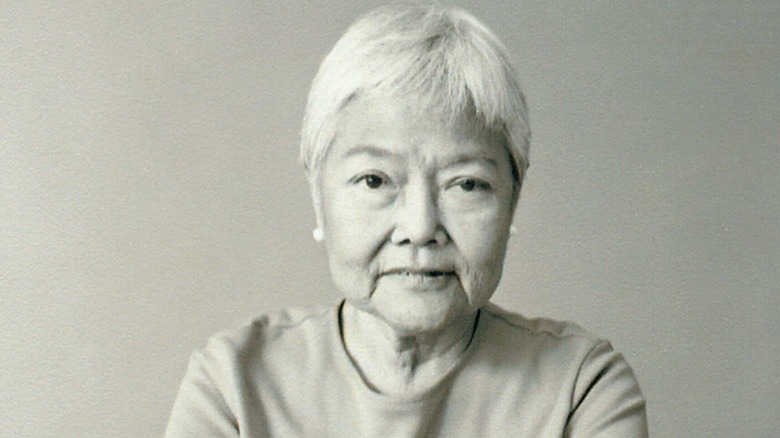

Doreen Fernandez as a food reviewer

Doreen Fernandez's entry into the world of Filipino food writing is the stuff of local legend. She had been married to designer (and known gourmet) Wili Fernandez for about a decade when The Manila Chronicle approached him to write a food column. Doreen Fernandez would later say in a New York Times interview: "He said, like the male chauvinist that he was, 'Sure I'll eat, and she'll write.'"

Her early restaurant reviews were published under a byline shared with her husband. But even then, as her editor Chelo Banal-Formoso shared in her obit, Fernandez did things her way. "She was never mean. We could tell she didn't like a restaurant she visited only from the lack of lilt in her prose. We knew she liked the food when her words came out like a caress. When she didn't, there was much she ignored and she tended to be brief" (per Facebook).

What Fernandez did enjoy doing was using the power of her pen to first capture the sensory pleasure of a good meal, and then using those same words to help her readers understand the whats, the whys, and the hows that made sense of the meal — and the cuisine — as a whole. As noted historian Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett points out in Gastronomica, Fernandez used words to paint a culinary landscape that Filipinos could relate to, understand, and be proud to call their own.

Doreen Fernandez's groundbreaking book

Fernandez wasn't content to stay in Manila. She crisscrossed the Philippines to reach out to farmers and fishermen, prominent chefs and waiters, to roadside market vendors and their customers, all in an effort to make sense of Filipino cuisine — which she admitted to the end was difficult to describe. It would be no exaggeration to say she had spoken to everyone, and it was because of this that she was able to present Filipino food as "a Malay matrix, in which melded influences from China and India ... Arabia ... Spain and America" (per Gastronomica).

Fernandez's efforts are showcased in the many books and columns she left behind when she passed in 2002. One of those books, "Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture," is hailed as groundbreaking because it became the lens through which the world could see Filipino food for what it's actually all about. Fernandez herself described her book as a teaser — a "taste," if you will, of all the cuisine had to offer, from its dishes and its flavors, to the historical context in which these same dishes might have evolved.

Small wonder then, that one former New York Times food editor Raymond Sokolov called Doreen Fernandez "the most impressive food writer and historian I ever encountered."