Ojen: The Ultimate Bottle Guide To A Louisiana Classic

The Mardi Gras is an annual festival atmosphere that grips the city of New Orleans. Nothing is as closely tied with Fat Tuesday in The Big Easy as Ojen. Pronounced as "oh-hen," the liqueur has been a favorite of New Orleanians since the 1800s, and the Ojen cocktail is a go-to drink during festival times. Like ouzo or sambuca, it's a clear, distilled, and anise-flavored spirit that originated in the Mediterranean region of Europe.

The recipe and exact botanical blend aren't widely known and may have actually changed as time has gone on. The spirit, as popular as it is, was saved from extinction a few years ago — and that process required a bit of reverse engineering. Still, there is certainly some kind of distilled base spirit involved and an unmistakable taste of anise. A strong sweetness also suggests you'll find a good amount of syrup among the bottle's ingredients.

Despite finding a niche on the other side of the Atlantic, the drink itself actually originated in a small town in Europe. After over a century, all of the distilleries that produced Ojen in its original country had closed their doors, and these days, it's only manufactured in Louisiana.

What does Ojen taste like?

The first thing you're likely to notice when sipping on a glass of Ojen is a strong taste of black licorice. This flavor comes from the anise, which is the main botanical used in the spirit's production. The anise and the syrup, which have likely been added to the liquor, combine to make Ojen taste incredibly sweet. You're also likely to notice hints of spice through to the finish.

Ojen's flavor has been likened to a sweeter and mellower version of absinthe, another botanically infused spirit. Though it is worth noting that the spirit also has a far lower alcohol content than absinthe, so it should be far milder on the palate. It is also similar to sambuca, in terms of taste anyway. The two spirits differ when it comes to the mouthfeel, as an oily sambuca will likely coat the drinker's mouth, whereas straight Ojen often leaves the mouth quite dry.

How is Ojen made?

The exact recipe for Ojen isn't widely known, even after the spirit was brought back from the dead a few years ago. However, similar beverages are traditionally made by putting anise with other botanicals, which vary depending on the producer's recipe, into wine or wine dregs. This is then left somewhere warm and dark for a few days, to give the botanicals time to do their stuff. The resulting decoction is strained and then distilled resulting in a clear spirit with a strong licorice flavor. The sweetness associated with Ojen almost certainly comes from a basic spirit being added to the liquor following any distillation.

While home distillation is a definite no-no in many places, you can sort of make your own Ojen by using a similar method to the one people use to infuse gin. If you add anise along with simple syrup and spices like fennel, cinnamon, and nutmeg, you might get somewhere close. As with the current Ojen recipe, your home-infused will require some experimentation if you want to get the flavor close to the real thing.

Ojen is often mixed as a cocktail for Mardi Gras

As with other botanical liqueurs, you can enjoy Ojen neat as either an aperitif or a digestif. However, this isn't the way things tend to be done in Louisiana. Ojen is most commonly used as part of a very simple cocktail, which has a very distinct cloudy pink color in the spirit of Mardi Gras.

To make the Ojen cocktail, fill a lowball glass with crushed ice and pour over a couple ounces of Ojen. Follow this up with a few dashes of bitters, specifically Peychaud's Bitters if you want to keep things authentic and give your cocktail that pink color. You will need to add a ¼ ounce of simple syrup, an ingredient you should prepare ahead of time. Finally, twist a lemon peel over the top to give a hint of citrus. It's that simple.

If you need any more evidence that this is indeed the way to do it, flip over your bottle of Ojen to find the recipe for the Ojen cocktail.

Ojen can take the place of absinthe in a frappe

The Ojen cocktail isn't the only way to enjoy the rare spirit over ice. Legendre Ojen also works well as a substitute for absinthe in a frappe. It is similar to absinthe in a few ways; it has a similar but milder and sweeter flavor profile. It also goes cloudy to the point of opaqueness when introduced to ice or cold water. The frappe might make you picture some kind of coffee-based beverage, but they do things differently in New Orleans. As a result, it's a lot closer to a mojito than a mocha.

To make an Ojen frappe, add two ounces of the spirit to a cocktail shaker half filled with ice, along with ½ ounce of simple syrup. Shake to chill the mixture, before pouring it into another glass filled with crushed ice. Garnish with mint, and you're done.

The name frappe refers to a technique where crushed ice is used to give the cocktail a slushy-like texture. An influential bartender you should know about is called Constante Ribalaigua Vert, a famous prohibition-era mixologist who made his name serving Americans headed to Havana, Cuba, to indulge in a drink or two when it was banned in their homeland. There are many kinds of frappe, including the not-necessarily alcoholic, coffee-based one. Though the absinthe or case Ojen-based frappe are drinks people strongly associate with New Orleans.

Ojen vs. Sambuca

Ojen and sambuca have a lot in common. They're both clear anise-based spirits that originate in southern Europe. They're both clear, distilled, and tend to hover around the 40% alcohol mark. Drink either, and you'll immediately be greeted by a very strong licorice flavor. Scratch beneath the surface and there are some differences. Sambuca is proudly Italian and quite popular — you'll likely find at least one bottle in any bar or liquor store you stroll into.

Ojen originates in southern Spain and is about as niche as a drink can get. Ojen is a bit more versatile because it can be enjoyed as an aperitif or digestif, whereas sambuca usually makes its way to a dinner table after the meal. Ojen is also far sweeter and lacks the slightly bitter aftertaste sambuca tends to have. While there is only one kind of Ojen, there are multiple types of sambuca: red, white, and black. Finally, there is currently only one company producing Ojen, whereas there are many manufacturers producing sambuca and quality can differ between them.

Ojen originated in Spain

While New Orleans is the only city where Ojen is currently produced, the liqueur actually originated and got its name from, a tiny town in Andalusia, Spain. Ojen, the city not the drink, is in the southern part of Spain and once derived a significant portion of its income from the production of Aguardiente de Ojén — once Ojen's full name.

The drink itself was first produced in the region in 1830 and exported around the globe. One of the areas it landed was New Orleans, and the locals there developed quite a taste for it. Unfortunately, the last company to produce Ojen in the region went out of business in the early 1990s, leading to an end of the spirit's production in Spain and, for a time at least, globally. Even though New Orleans has a very heavy French influence, it is responsible for reviving the spirit.

Sazerac revived the Ojen we know today

If you walk into a liquor store in Louisiana, Texas, Illinois, New York, or Washington state — there's a chance you'll see a bottle of Ojen on the shelf and it will be yours for less than $30. For a time though, you couldn't get it anywhere, reduced to a handful of bottles residing in the liquor cabinets of private collectors. If not for the efforts of a New Orleans-based liquor company called the Sazerac Company, this piece you're currently reading would be a retrospective on a long-lost liqueur.

When the last Spanish producer of Ojen called it a day in the early 1990s, a New Orleans liquor store called Martin's Wine Cellar bought up every bottle of the local favorite it could get its hands on, said to be around 6,000 in total. Over the years, that stockpile dwindled and the last bottle of the last run was finally sold in 2009. Most were likely used and, no doubt, several are still the pride of a private collection in the Pelican State.

The New York Times reports the Big Easy-based Sazerac used a series of lab tests, some reverse engineering, and managed to recreate the legendary beverage. Ojen bottles returned to the city's shelves in late 2015, which gave people plenty of time to get their hands on one before 2016's Mardi Gras (via Barina Craft).

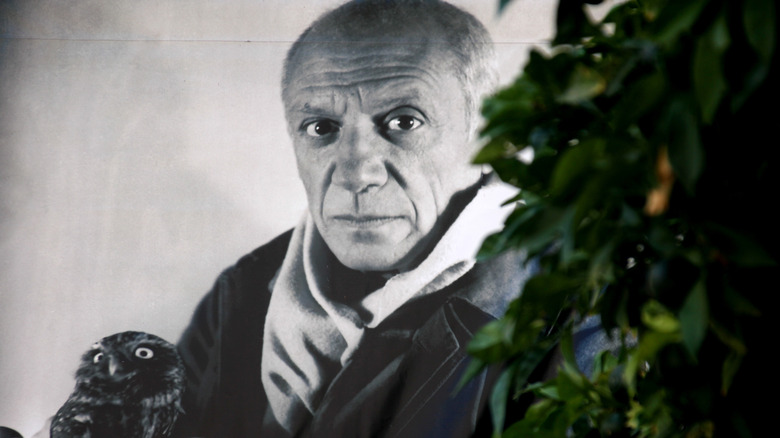

Ojen inspired one of the world's most famous artists

If you ask most people what drink inspired some of the world's greatest artists, absinthe is the one that immediately springs to mind. But, the wormwood-based beverage's minor cousin has also played its part in art history and has even appeared in a painting by arguably the most famous artist of all time. Pablo Picasso, who was also from Spain, put the iconic coffin-shaped bottle of one of his home nation's most famous tipples in his 1912 work: "Spanish Still Life."

Although staring at a Picasso and trying to pick out individual objects can be a bit difficult, there is no debate that it is a bottle of Ojen, and it is there deliberately. The word "Ojen" is also clearly visible on the bottle, and the bottle itself also appears on both preparatory sketches the artist did before the final work was painted.

The famous drink has also appeared across other artistic mediums. Hemingway mentions several characters drinking it in "To Have and Have Not." Hemingway made several trips to Spain while the novel was being written and found work as a correspondent during the Spanish Civil War — so he could have been only too familiar with the Spanish spirit.