Michael W. Twitty On Bringing Black Identity To The Hanukkah Table - Exclusive Interview

Food historian Michael W. Twitty defies easy categorization, a fact that suits him just fine. The James Beard Award-winning author, most recently of "Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew," is a self-described itinerant — "because that's the only way to do amazing things," he says. He's "organization-phobic," an academic who rejected the academy in favor of his own ongoing, self-guided education into the roots of diasporic cuisine.

"I've never had two feet in an institution for too long," he says. "There are a lot of people who, when they talk to me, ask, 'Where's the farm? Where's the restaurant?' Those things would tie me down. I like being a guest. I don't like being a permanent resident."

Twitty prefers to let his passions direct his energy, and he's dedicated himself to a deeply personal life's work. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., he can trace his own lineage back to the African Atlantic slave trade, some Irish ancestry, and more distant Ukrainian-Jewish heritage — identities he embraces, imbuing them with his singular individuality.

When he sat down with Tasting Table, sporting a kippa emblazoned with the words, "Shalom, Y'all," paired with his "very gay, half-naked merman T-shirt," he was keen to discuss the African roots of American barbecue, the politics of food, and even some tips to make your Hanukkah table a little more delicious this year.

A lifelong relationship with Colonial Williamsburg

You came to your love of food and history when you were very young on a visit to Colonial Williamsburg. Can you talk about your ongoing relationship with Williamsburg?

I've worked with them for about a decade now, off and on. In 2017, the same year ["The Cooking Gene"] came out, I was the first Revolutionary in Residence, which is deep because there is definitely an old-school approach and a new-school approach to how one does living history, especially in the South.

The Sankofa African Virginian Heritage Garden is still going strong with the garden and landscaping that I established. I'm glad that project is alive and well, whether I'm there or not. Right now, I'm trying to work out a research program where I'm documenting every single food we know about that was consumed by African Americans in the 18th century. I want to be able to use all the tools of the 21st century to do that so that there is no longer a question or a debate over what that looks like.

The African heritage of American barbecue

I'm fascinated by the history of American barbecue and its origins in the Mid-Atlantic region of the country you come from. Cooking styles, rubs, and sauces evolved from a variety of sources including the traditions passed down among enslaved Africans and their descendants. Can you talk about some of those traditions and where we might still see their vestiges today?

Go to Senegal, go to Nigeria, go to Ghana, go to Congo. It's right there. It's particularly important in places where there is a Muslim population, which is interesting. All of those countries in West and Central Africa have a definite barbecuing tradition. In Central Africa, where a third of our ancestors came from, you have the peri-peri tradition, which is marketed as South African or Portuguese, but no — it's Indigenous. It's peppers and palm oil and muamba, the sauce you make from them that you eat with everything.

If you go to D.C., where I'm from, people talk about "mambo sauce," the savory sauce that goes with wings, barbecue, and other things from the D.C. area. Like many other things in Black American culture, not everything is a direct line. Sometimes people forget why they say things and do things, and it's because we've been cut off [and] reconnected from our roots.

Barbecue is such a contested area because barbecue has a lot of money and power associated with it. The African tradition got pushed to the side in the narrative of American food writers — number one, because they don't know Africa. Number two, there was this push-pull between writers and historians who gave only a pittance nod to Black creators, Black chefs, Black culinarians, Black barbecue men.

People are very skeptical when it comes to work like mine. How many books have I been treated to where they say, "Barbecue comes from the French, 'from the head to the tail,'" or where people blindly accept the narrative that barbecue is an origin story built on Arawak and Carib traditions? I am in no way going to deny Indigenous people their traditions and culture and contributions, especially as somebody who is part Indigenous in my genetic heritage and family history. But the fact is, there were no quadrupeds in the Caribbean that were barbecued for ten hours until the Spanish and the Africans showed up.

What is the number one thing they love? Goat and chicken. Where do you find them things? Africa. It took basically under a decade for [these traditions to migrate over] after the transatlantic slave trade began.

The many origins of the word 'barbecue'

There's a lot of controversy around the etymology of "barbecue." Understanding where the word comes from may help clear up some other issues around the roots of American barbecue. What is your understanding of its origins?

A couple years ago, my friends at the Atlanta History Center had an exhibit on barbecue in the South. They took seriously what I said and incorporated it with attribution in their exhibit. I talked about how there's barbacoa [in Spanish], there's barbe á queue [in French], then there's babake in Hausa. There are 50 million Hausa speakers. The Hausa are traders and cattlemen, and they range from Senegal all the way to Cameroon, Niger, and beyond. They had their own kingdom for quite some time. "Babake" means to grill, to toast, to roast, to use wood up for a very long time, to cook some meat. What does that sound like?

Barbecue as resistance food

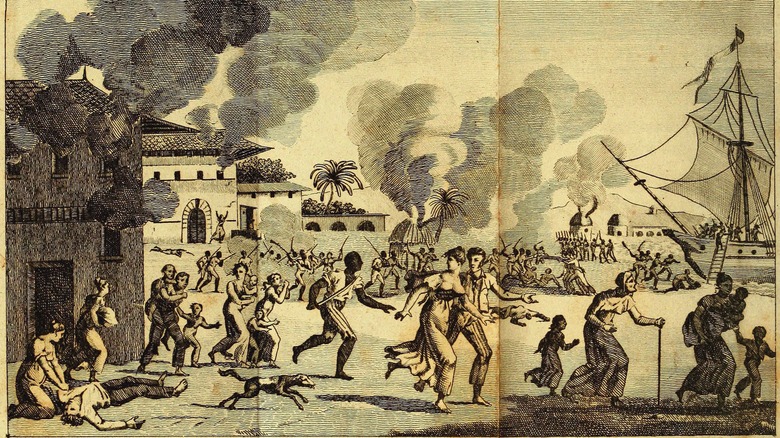

Michael Twitty (continued): When I wrote that piece for The Guardian many years ago, talking about barbecue as resistance food, the right wing lost its damn mind. "I guess we can't eat barbecue now!" I'm like, "That's not the point." The point is not whether you can eat barbecue. The point is, I want you to think about Gabriel Prosser's rebellion, Nat Turner's rebellion, the Haitian Revolution, and many other flashpoints of rebellion by enslaved people. At the start of those events was a barbecue, a gathering.

In terms of the Haitian revolution, it's even deeper because they sacrificed the black pig and barbecued it. They're invoking Ezilí Dantor, who is definitely on the Congo side of Haitian Vodou and is a very strong, violent, forceful loa. [White American food culture doesn't] want to think about that, because now you're into African spirituality and Vodou. It's scary and dark and tough. Also, who's the pig? Le Blanc! That pig may have been black, but the famous words at the start of the Haitian Revolution: "May the blood of this pig flow like the blood of our masters."

[American food culture] didn't like that. They didn't dig that. They were mad at me. I don't really give a damn; that's our history.

A personal tapestry of spiritual traditions

You converted to Judaism when you were 25 years old, so you didn't grow up in a household where Hanukkah was a family tradition. Do you still have old family traditions you practice around the holidays? How has your chosen religion brought new traditions into your life?

When I wrote "The Cooking Gene," I did a lot of genetic [research], and I had heard stories about Jewish ancestors in our family. Then 23andMe says, "You've got a good handful of cousins here who have all four Jewish grandparents, all from Ukraine. They're all related to you." It's a blend of both worlds. But by the time I learned that, it didn't matter to me anymore. I had taught over 1,000 kids [in Hebrew school]. I've now been a part of [the Jewish] community for 22 years.

I grew up in a neighborhood that was at the confluence of the Conservative, Reform, and Orthodox congregations that served that part of Silver Spring-Wheaton. Now, it's more Orthodox than anything else. It's a huge community in which several friends of mine, who are also African American, live as Orthodox Jews.

I take advantage of Juneteenth, Kwanzaa, Dr. King's birthday, Malcolm X's birthday. There's a weaving and pulling together of different things that speak to the spiritual values that I have. And the Jewish calendar does not let up. You have a dozen major holidays, and that's probably undercutting it.

Michael Twitty's Hanukkah table

What do you do for Hanukkah?

I do the candles. I do maybe one or two good dinner parties, depending upon who I can get together, who's exhausted, who's not exhausted. I tend to make foods that incorporate some olive oil because the miracle of the oil is important. Stuffed and wrapped foods are important, [representing the] concealed or hidden presence of God, as well as having to conceal and hide things to protect ourselves, which is also a theme. Sambousek, samosa — those foods are very common for me on Hanukkah. Also, beignets and puff puff — which is the West African version — I make those.

It's one of the three times a year that I'm obligated to make fried chicken because of Hanukkah. I'll make it with matzo meal, which is what makes it different. I make everything-bagel salmon this time of year, West African brisket, jollof rice ... as many salads as I can find, and roasted vegetables with olive oil. I want as many vegetables as possible.

Then [there's] the array of fried foods that dominate the holiday. Latkes are important. This year, I'm going to try something a little different. The Lumbee of Robeson County, North Carolina, have inspired me. They have a collard green sandwich they do at their powwows [with hot water cornbread]. If I do my Louisiana latke recipe, I have scallion and red pepper and other goodies in it, and I can use that as the bun for the collards.

I'll be very simple about it. I tend to grate the potatoes. For Louisiana latkes, I throw in a little chopped celery, a little bit of grated yellow onion, chopped scallions, and red pepper. I put the trinity in it, a little creole spice, a Cajun spice.

I fry up the latkes, and I'll do a very basic spicy collared sauté. I don't even think about it. I do chiffonade on the collard greens. Very thin, long strips — that's the key, like noodles or ribbons, the barest amount of oil in there, then sauté them up. I'll put the collards in between [two Louisiana latkes] and we have a collard green sandwich.

The secrets of West African brisket

Do you do brisket for Hanukkah?

Last year, I did the West African brisket. I got profiled by the New York Times during Pesach, but I've done it for quite some time. It's suya spice and bell peppers, onions, tomatoes, ginger, garlic, and turmeric.

Like any other brisket, you sear it. Then you throw in the onions, bell peppers, garlic, and ginger and let it do what it's going to do for a couple hours — about four hours [in a Dutch oven] as low and slow as you can. Get it as soft as you can, letting those seasonings mix together. Tomatoes will come after. They're the last thing, and the suya spice — salt, garlic, onion, Indigenous spices like cardamom, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and other things. There's hot pepper [and] black pepper, which are very spicy and floral and aromatic. It's very pungent and deep. It's all better if you can let it sit overnight in the fridge.

One secret ingredient that I tend to use in my West African brisket that is not in the recipes is country onion. Country onion is really not onion; it's a byproduct of a tree from West Africa that has more of an onion taste than an onion. It'll hit you in the nose and it's very onion-y, very allium-y, but it's not an allium. It smells super amped up.

Do you do the Manischewitz thing?

On Pesach, it's an absolute must to have at least one bottle among the many bottles of whatever. I encourage people to bring better kosher wines, but I will always do at least two of my four cups with Manischewitz. That's American Jewish tradition right there.

It makes the best secret ingredient in tomato-based briskets. Instead of adding anything else that's sugary or sweet, it really does transform when it's cooking in a pot with other things. Also, I do a candied yam this time of year with Manischewitz. I use either the blackberry or the grape and cook them with sugar and spices until they're mushy. I use it as a sauce. I use it as part of the liquid in the pot — Manischewitz, margarine, sugar, and spices.

Why Jewish food gets a bad rap

What are the ways Jewish cuisine has evolved as it has migrated out of Eastern Europe and into the U.S.?

In terms of Ashkenazi Jewish cooking, it's regional. It wasn't [developed in] one place. It was spread across probably around 20 modern countries, each of which have their own unique spin on these foods.

It has a bad rap. "This food wasn't healthy. It was bland. It was gray." There's a lot of misogyny in this critique. You're blaming the mamas and the bubbies. These folks don't understand that the food was colorful, the food was seasonal, but what made it into the tenements? When you're trying to make it in America, you ain't got time to jazz it up in your little postage stamp apartment living with twelve people. You did what you had to do.

Now, we have a new generation. The Gefilteria, my friends over there, are making [fresh] Yiddish heritage food. It's great because the emphasis is on fresh ingredients and colors.

The false narrative behind soul food

Soul food is often maligned as unhealthy and blamed for perpetuating a health crisis among African Americans. You argue that perception is rooted in a history that erases Black agency.

There's this idea that all this food's going to kill you — no. Greens are great for you. Sweet potatoes and okra and melons are great for you. Lean proteins and fresh proteins that are not full of mercury and poisons are good for you.

The idea that we're still arguing about, "Soul food is part of the problem" — how? Soul food is not the fast food appropriation of country food. That's not soul food. Processed food is not the same thing. I don't care if they put the same label to it; it's not the same food.

I was on this podcast, and [the host's] memo was, "How did we get that soul food? It's bad. A white man ..." I'm like, "No, the white man got nothing to do with it." Scraps didn't get thrown down to Black people and they made them taste good. That's the usual narrative, but it's a false narrative.

It's the idea of some white person from some white-column mansion walking past a slave quarter throwing down hog guts in the mud at somebody and going, "Here, cook this. Here's what we have left over from our dinner table." You have 50 to 100 Black folks and seven white people. It's stupid. The math ain't mathing. You're taking away the agency and ownership and ingenuity of Africans and enslaved people.

In many places where [enslaved Africans] were exiled, they set the tone for the entire diet. It's obvious to anybody who has been in the Deep South: Europe did not win. Indigenous America and the African Atlantic won. Same thing in Jamaica; same thing in other places like Brazil.

Yiddish, AAVE, and traditional foodways

You've talked about the intersection points between Yiddish and African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and how you reject the idea that they are the "bad" step-cousins of their linguistic lineage. Rather, you talk about how they are languages unto themselves that evolved to pass down, among other things, the cultural foodways of their speakers. Can you say more about the relationship between language and traditional foodways?

My point with the book, ["Koshersoul"], was not to define a genre of food — that's arrogant — but to talk about all the different ways that Jews of African descent, Black Jews, have made kosher soul food according to their own taste and tradition.

These two traditions — African Atlantic and the Ashkenazi Jewish diaspora in particular — have been maligned because it was the food of the plantation and the ghetto and shtetl. There's this common idea: "It's low class. It's not as high-end. It's cheap. It's the food of the oppressed and the oppressed mindset. The mothers are to blame. The mothers fed us, but they were also killing us. They're still killing us. It's not that innovative, not that creative." But if it's not that innovative or creative or useful, how come we're still doing it and still marketing it, commodifying it, still popularizing it? What's going on?

It's like "Yiddish is the joke language." No, it's not a joke language. Yiddish is an extremely expressive, to-the-point, emotional, onomatopoeia-rich language. AAVE is not slang. AAVE is its own thing comparable with other Black Atlantic languages in the Americas that are a fusion of African grammar, syntax, and tone, with whatever European languages, with whatever Indigenous languages were present, et cetera. It's because we needed a lingua franca that we could communicate in across the different ethnic groups that were brought from West Central Africa and beyond to the Americas.

It's hard to explain to people what AAVE means to me because I remember getting lectured — as an adult — about slipping into vernacular. I told them, "First of all, sweetheart, I understand that I'm speaking the vernacular. It means that I'm comfortable. It means that I'm speaking the truth to you. Now, the minute I start speaking only standard English to you is when you know I'm lying." That shut people the f*** up, because it's basically saying you want me to talk your way. Your way means I'm putting on a mask.

That's why I pushed back in ["Koshersoul"]. For me, it's one of the clear and obvious points of continuity between the two diasporic civilizations.

How Michael Twitty uses food to tell stories

So much of your work focuses on food and its role in personal and cultural identity. You've evolved your own identity around your background, history, your sexuality, and your religion. Stepping away from your role as ambassador and historian for a second, what are the foods or meals that you think are most defining of who you are?

The biggest thing for me has been understanding how I come to certain recipes and things. There's an active curating of my life, that things should tell a story about me. I do that for a reason because I realized that — it freaks me out — but our time here is so short and our time gone is so long that one has to make a statement. One has to have a presence. I'm grateful that I've had role models to look up to like André Leon Talley and other people who, no matter what people thought about them, made a statement about who they are. It's very important to me.

For me, kosher soul rolls come to mind. I made that for Andrew Zimmern the first time I was on TV with him. They're a great example because I first learned about soul rolls in the Deep South, and I was like, "It's basically a Black egg roll." Then, when I was going through Borough Park in Brooklyn, somebody had pastrami egg rolls. It's kosher, and I was like, "Let me get one." Walked in, got it — I was like, "This is really bland." But I liked the pastrami part.

Pastrami, collard greens ... I love me some spring rolls and Chinese food. Throw some scallions in there. Throw some vegetarian oyster sauce in there, hoisin, hot pepper, more garlic, more ginger, bam, bam, boom: kosher soul rolls. It's something that speaks to all the things that I find delicious and wonderful and great in the world. It's fun, it's different, it's interesting, but it also pays homage and tells a story.

Essentially, that's who I am. I tell stories. I'm a griot. That's what I aspire to be as an elder, and my elderhood is coming fast.

Why a spring roll? Because we ain't got time. Eat it and go. Keep running. Keep going.

Read Michael W. Twitty's new memoir, "Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew."

This interview was edited for clarity and length.