10 Red Flags At A Taqueria That Should Make You Turn Around, According To A Taquero

You can easily find tacos and burritos in most areas of the U.S. in roadside stands, food trucks, walk-up windows, and fine-dining restaurants. It's hard to discern their quality by looking at the sign and menu, but some telltale signs should make you second-guess your decision to stop in.

Rene Valenzuela, chef and owner of Rene's Mexican Kitchen in Tampa, Florida, is a lifelong student of regional Mexican cuisine who's appeared on television shows like "Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives," "Man v. Food," and "FoodNation." He warns diners to learn to discern between "Mexican," traditional regional cuisine, and "Mexican-inspired," which could mean anything wrapped in a tortilla.

Although I'm far from knowledgeable, I'm familiar with many styles of Mexican cooking. Additionally, in my almost four decades as a chef, I became pretty adept at flavor pairing and achieving balance. But Valenzuela's knowledge of the regional dishes of Mexico borders on encyclopedic. With his help, I compiled this list of warning signs — like over-elaborately garnished tacos — that should send you on your way when encountering them in a taqueria.

Bragging about the size of their burritos

One of the most disappointing things about burritos is the popularity of "huge" versions of them. The roots of giant burritos lie in San Francisco's Mission District, where two competing restaurants claim to have developed the Mission-style burrito. In this style, two tortillas make room for extra fillings. In a 2019 Eater essay, Gustavo Arellano outlined how fast-casual restaurant Chipotle spread the idea of Mission-style burritos across the country, making them ubiquitous and bringing about the demise of generational local burrito cultures in places like Denver, Colorado — replacing "distinct burrito genres" with the overstuffed behemoth that's now the yardstick by which burrito worth is measured.

Valenzuela lists giant burritos as one of his red flags. If a restaurant claims, "We have the biggest burrito in Chicago or Texas or Florida or whatever," Valenzuela says you should pass it by. French fries (really), rice and beans, queso, guacamole, and too much meat make a visually impressive, hefty burrito with no balance of flavors. "They just try to provide this huge meal for the cheap or something," Valenzuela says, comparing the burrito's size to a small rabbit. If you're dining for value, a giant burrito combines calories with economy. But if you're seeking the subtlety of flavors and enjoy the harmony of ingredients, it's better to turn around and pick another restaurant.

Serving more than one cuisine

U.S. diners skew towards familiarity when picking a restaurant. Valenzuela explains that restaurants selling Honduran or Peruvian food, for example, sometimes don't get the economic traction they need from their chosen cuisine, so they wander into adding the familiarity of tacos to bolster sales. But Valenzuela thinks that's a red flag. He cites the difficulty of mastering one cuisine — let alone two — and says one, if not both, will suffer.

"So if you go to a place and say, it's Cuban and also tacos, it's like, uh-uh," he says.

Valenzuela isn't gate-keeping Mexican cuisine against people from other countries, but rather commenting on the rigors of maintaining a multi-cuisine menu. Attempting to uphold the quality and freshness of two disparate cooking styles can be extremely difficult, and there's a large possibility that one or both will suffer from the divided attention.

Then there's a flavor clash. The cuisines of one South American, Central American, or Caribbean country might not marry well with that of another. So, seek out restaurants specializing in the cuisine of one locality or a specific region within that country for the best experience and representation of that cooking style.

Covering too many regions

Mexico is a large country, about three times the size of Texas. Its climate and topography vary greatly, encompassing mountains, deserts, coastal plains, jungles, and other woodlands. This diverse geography creates highly regional cuisines, which we incorrectly refer to as "Mexican food." There are seven culinary regions in Mexico and sub-cuisines within each of those regions. Using "El Norte" as an example, the region encompasses the Northern Gulf Coast to the Baja Peninsula. In between are mountains and deserts, and each area has its own cooking style based on the available ingredients and local traditions.

Valenzuela looks at that regionality and chefs who try to cook dishes from every region. He typically sees them swing for the fences with iconic regional dishes, which are often the most complex and nuanced offerings. That bold approach doesn't often meet its mark.

"They'll make mole negro from Oaxaca, carnitas from Michoacán, cabrito from the north, cemitas from Puebla, and cochinita pibil from Yucatán," Valenzuela says. "It's like, whoa, whoa. People are very ambitious, but they don't understand." For comparison, he explains that the approach is like him opening an "American" restaurant and filling the menu with Carolina BBQ and complex New Orleans dishes, expecting excellence and harmonious flavors from both. He explains that it's not unusual to find taquerias in Mexico specializing in a single dish. The American demand for variety in the U.S. drives chefs to expand — often with clashing flavors and ingredients — making a non-cohesive menu.

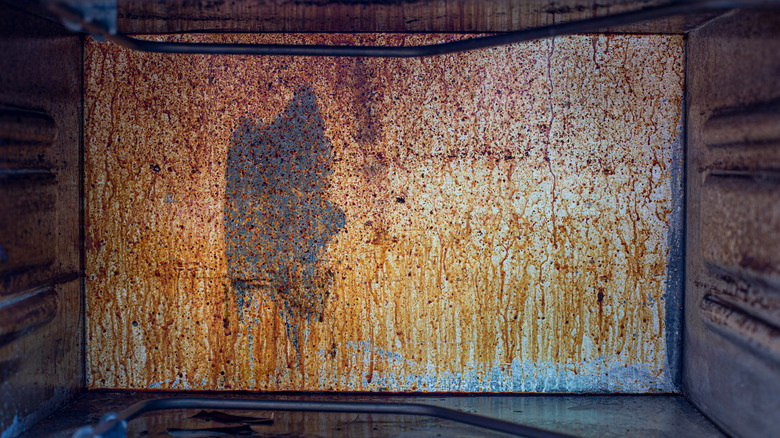

The place is dirty

This topic isn't reserved strictly for taquerias but applies here and in other restaurants. If a food truck has fetid standing water under it or a walk-up taqueria has a trash-strewn parking lot, things don't look promising, and you should trust your first impression. Sit-down taquerias give you more customer-facing areas from which to draw.

"Sticky tables — man, they drive me crazy. You put your arms on it, and your forearm kind of glues [to] the table," Valenzuela says. He goes on, saying stains on the floor or dirty bathrooms, in addition to the items already mentioned, "make you wonder that if these are the areas that the customer sees, how is it going to look in the areas that we don't look at?" Food handling and storage areas out of public view could receive the same lack of attention, presenting food safety issues from mold buildup, mildew, pest infestation, or unsafe food handling. If any restaurant looks or smells bad, trust your gut; it will thank you for walking away.

Cheap proteins

Diners have long regarded tacos as cheap food. They're still relatively inexpensive, but if you find a deal for a steak taco for $1.89, no, you didn't. Valenzuela says, "I'm thinking, 'How in the world?' You know, steak's expensive. What are they doing?" The same can apply for $20 all-you-can-eat propositions, too.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the all-food Consumer Price Index rose 25% between 2019 and 2023. While many people are looking for value in light of that, a low-cost beef or chicken taco indicates one of two things: Substandard or substituted meat or extremely small meat portions with an overloading of garnishes (like onions, cilantro, pico de gallo, radishes, or pickled onions). "So places are too dirt cheap ... they're scamming because I know what the cost of food is," Valenzuela says. Given the potentially misrepresented meat — or a lack of anything approaching flavor balance from the taco's garnishes — it's better to walk away and find a more realistically priced taco.

Shelf-stable tortillas

A taco only has three parts: The filling, the garnish, and the tortilla. Neglecting any of these components challenges the quality of the taco, and the most overlooked element is, unfortunately, the tortilla. Consider the tortilla the same as the bread of a sandwich. You might raise an eyebrow if you see a sandwich shop serving its offerings on shelf-stable white bread instead of a freshly baked loaf. Likewise, seeing a taqueria with shelf-stable commercial tortillas on the counter is a good sign to turn around.

Valenzuela is against mass-marketed, shelf-stable tortillas. "You can open them and smell the chemicals," he says. "It's also a little bit sweet, which is kind of weird for a tortilla." Indigenous cultures of Mexico made tortillas via a complicated, specialized process called nixtamalization. Corn is soaked, cooked in an alkaline solution, ground, formed into tortillas, and cooked. Think of tortilla making like you would a baker who starts with whole grains, grinding their flour before baking to get the best bread. In homes and tortillerias, cooks likewise hone their craft for years to master the art of tortilla-making.

Most commercial tortilla manufacturers instead use ground corn, never developing the full flavor of the tortilla and then adding stabilizing elements to make them safe to store at room temperature. Valenzuela sources nixtamalized tortillas from Texas — shipped frozen to his restaurants in Florida — as he holds a properly-made tortilla as a line not to cross when deciding where to dine.

Canned beans

Beans are a building block of Mexican cuisine. Valenzuela says if you see canned beans on a shelf in the kitchen, it's time to leave that taqueria. "Don't walk," he says, meaning you should depart with haste. He says the type of beans used depends on the region, and canning destroys the nuances of those beans.

It's not widely known that canned beans are cooked in the can as part of the preparation process, and the can's metallic flavor can leach into the beans during that step. Valenzuela is emphatic that no matter how much onion, garlic, and chiles one puts into canned beans, you'll never overcome that flavor, adding that he can tell which brand of canned bean a restaurant uses by taste alone. In a culture where home cooks learn to cook beans at an early age, the intricacies and nuances of those beans are more apparent than to a casual observer, but that shouldn't lower the bar, according to Valenzuela.

Instant or par-boiled rice

Rice is as essential as beans in Mexican cooking, and starting with an inferior product doesn't bode well for the end result. Mexican rice cooking is a different animal than boiling or steaming, requiring a longer, open-vessel cooking process. The technique's basis is the rice itself, calling for a long-grained variety, like the federally protected Morelos rice.

Using generational recipes, home cooks toast the rice in oil before adding pureed vegetables and seasonings, along with the desired liquid, and allow the rice to cook slowly. Valenzuela says boxed or bagged instant or par-boiled rice lacks the flavor, texture, and character necessary for this staple food, and starting with those types of ingredients guarantees a subpar end product. It's not simply the finished rice that worries him; the lack of attention to that basic ingredient detail sends up a red flag, as it casts doubt on the rest of the menu's quality.

The wrong dairy products

Valenzuela explains that Mexican dairy products are unique and not easily substituted. That's why the wrong types will send him out the door. If a taqueria offers yellow cheese instead of queso blanco, it's a red flag. "What's it called? Cheddar? We don't have that in Mexico," he says, laughing. Mexican cheeses tend to have a subtler flavor than the sharpness of cheddar. Using the cheaper, more readily available cheddar throws the balance of the taco's flavor off — often overpowering the other ingredients — and the fattier cheese leaves a lingering mouth sensation.

Likewise, taquerias that use sour cream instead of Mexican crema are a deal breaker for him. Crema is less tart, with a sweeter dairy flavor than sour cream or crème fraîche. Crema is also thinner in viscosity than either, making it more pourable, covering the taco rather than sitting as a dollop on top of it.

Lack of salsa

Valenzuela, a stickler for details, explains a major point where Mexican cooking and other cuisines diverge. In many cooking styles, a chef prepares a meal that should be perfectly seasoned when it lands in front of the customer. Think about a lack of salt on the table in European technique-based restaurants or the lack of soy sauce or wasabi when dining omakase-style.

He says it's time to leave if a taqueria lacks salsa. He regards a chef who sees his tacos as perfectly finished as-is, with no need for additional salsa, as arrogant or failing to understand Mexican culture. "We want the tacos to be wet," he explains. He adds that another adjacent restaurant red flag is that all the salsas are mild in heat. He explains that while he's not a chile-head, he and others prefer small dabs of a hotter salsa to enjoy the chile's flavor as an accompaniment to the taco's contents.